Iberian lynx: Radical moves for world's rarest cat

- Published

It appears out of nowhere, stealthily slinking into view and well camouflaged against the dry Mediterranean backdrop.

We have been waiting in a cramped hide since the crack of dawn. And having been told that the chance of getting a glimpse of one of these beasts is vanishingly small, we have almost given up hope.

But suddenly, there it is: the most endangered cat on the planet, the Iberian lynx.

For just a second, it stops, staring at us with its kohl-rimmed, yellow eyes.

It is about a metre long, with a short, sand-coloured coat and leopard-like spots; it has large paws and a short, bobbed tail.

Then, distracted by a rustle in the grass, its huge black-tufted ears twitch. It crouches, pounces, and emerges back into sight a second later with a rabbit dangling from its mouth.

And, as quickly as it appeared, it is gone, blending back into the forest with its prized meal.

The Iberian lynx has suffered a catastrophic drop in numbers

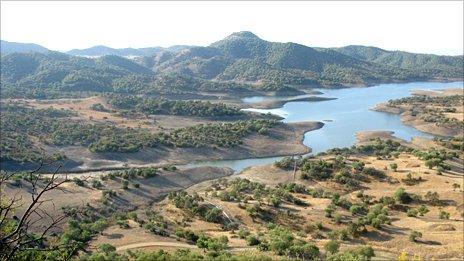

We are in Andujar, in Andalucia, Spain, which along with the Donana National Park, just south of Seville, is one of the last isolated pockets where the Iberian lynx can be seen.

This cat was once common across the whole of the Iberian peninsula, but from the 1960s its numbers plummeted, dropping from an estimated 3,000 to approximately 150 in 2005.

Habitat loss, poaching and road accidents all helped to push this cat to the brink of extinction. Disease outbreaks in the cat's main food source - wild rabbits - have added to the woe.

In the past decade, frantic efforts have been under way to conserve the last few cats.

Some of these approaches have been quite straightforward, such as implementing supplementary feeding stations that are used to boost the cat's diet when rabbit numbers are low - like the spot where we had been lucky enough to spy our wild lynx that morning.

Taking some wild lynx into captivity was a tough decision

But conservationists have had to get radical, too.

In La Olivilla, in Jaen, some lynx have been taken from the wild and placed in captivity with one key purpose: to breed.

Mariajo Perez, who runs the centre, tells me that this is not something that conservationists do lightly. But the situation was so bad, they were left with little choice.

She says: "It's worked really well so far. Our cats have been breeding really successfully - we have had eight cubs this year."

There are now about 40 cats in the centre, and other captive breeding centres in Andalucia have also managed to give a much needed boost to lynx numbers.

But the next challenge is to release the cats back into the wild, which could start next year.

Guillermo Lopez, from the Lynx Life project, knows all about moving animals.

He and his colleagues have been relocating some of the wild cats from the Andujar region to another carefully selected site some kilometres away, in the hope of establishing a new population.

He says: "So far, we have released six individuals - three males and three females. One of the females has had two cubs, so we feel very optimistic."

The team has been looking for new sites for the lynx - but could they move even farther afield in the future?

Moving animals from one place to another - or translocation - is becoming an increasingly common weapon in the conservationists' fight against extinction.

It helps to build up new populations and to ensure genetic diversity among ever shrinking groups of animals.

But scientists are now considering a much more controversial measure, which could one day mean that animals like the Iberian lynx are moved even farther afield.

Chris Thomas, professor of conservation biology at the University of York, UK, says: "The problem is that as the climate changes, the places that are best to put such endangered species back are not necessarily the same places where they historically used to occur."

He says that a changing climate will mean that some species will not be able to adapt or perhaps, due to geographical barriers, migrate to a new, more suitable home.

So instead, scientists will do it for them: literally pack up whole populations of species to shift them elsewhere. It is an idea called assisted migration (or assisted colonisation).

And it has many critics. Intentionally creating invasive and therefore potentially problematic species goes against just about every conservation convention. But the idea has been gaining momentum among some.

Prof Thomas says: "When I first heard about this, my immediate reaction was that this is crazy.

"But if we have a large number of species, potentially thousands, even hundreds of thousands, that are going to die out from climate change, we should at least ask the question: 'Is there anywhere else on Earth that they don't currently live in where they could in the future survive?'"

Things are looking up for the Iberian lynx

So far, examples of assisted migration have been few, but include a study that revealed the small skipper and marbled white butterflies did well when moved further north in the UK.

But Prof Thomas argues that we must at least start thinking about the feasibility of these kinds of moves - even when it comes to animals like the Iberian lynx.

He explains: "It is worth at least considering whether the Iberian lynx - this truly endangered species - could in the future find a home in, say, the British Isles.

"Of course, the answer might be that this wouldn't work. But we should contemplate such things given that the climate is changing, and the best places for a species are now on the move."

No place like home

For now, at least, efforts to save the Iberian lynx look set to remain focused in its home domain.

And scientists are optimistic about its future. Since 2005, numbers of wild lynx have steadily grown to around 300.

Miguel Simon, director of the Lynx Life project, says: "In the 10 years that we have been working on its conservation, the population in the Sierra Morena has doubled, and there has been a 50% increase in Donana."

The next step is to create three more populations in Portugal and Spain, at which point the cat would no longer be classed as critically endangered.

And with this, Dr Simon says, this magnificent Mediterranean cat could finally lose its unfortunate claim to fame as the world's most endangered feline, and instead become a symbol of conservation success.

- Published27 October 2010