Big cats to benefit from habitat fragmentation model

- Published

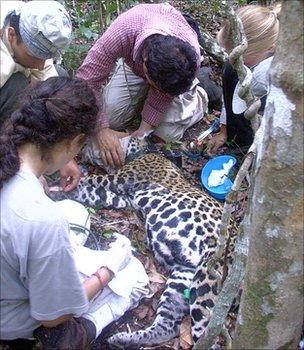

The team fitted tracking devices to 11 jaguars between 1997 and 2008

Experts have developed a statistical model that identifies where big cats are most likely to cross busy roads that cut through their natural range.

A team from Germany and Mexico describe habitat fragmentation as one of the greatest threats to large carnivores.

The model is based on a decade's worth of data collected from GPS and radio-telemetry collars fitted to jaguars in Central America.

The findings have been published in the journal Animal Conservation.

"Currently, most of the models that people are using are based on either expert opinion or on habitat availability," said co-author Fernando Colchero, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Germany.

"The problem with that is it is just like a snapshot of how the animal is choosing the habitat but it is not taking into account how the animal decides to move.

"What we wanted to do with our exercise is to incorporate the movement behaviour of animals. From the fieldwork that we have done, our results seem to be pretty accurate."

Power of prediction

Dr Colchero explained that the team's study was carried out in an area of the Mayan Forest, which stretches from south-eastern Mexico into Guatemala.

The main focus was on a main road between the Mexican cities of Escarcega and Xpujil, which bisected the big cats' natural range.

Between 1998 and 2007, 11 jaguars (seven females and four males) were captured. The five big cats captured before 2001 were fitted with radio-telemetry collars, while the six captured from 2001 were fitted with GPS devices.

The cats' locations were recorded four times a day, allowing the team to develop a data series plotting the jaguars' (Panthera onca) movements in the study area. This data allowed the researchers to develop an understanding of movement behaviour.

"We actually found that males were much less shy towards roads than females," Dr Colchero told BBC News.

"When we used the model to simulate how the jaguars moved in the landscape, we found that males could be found close to areas that are somewhat populated (by humans). However, females would definitely avoid those areas.

"When we simulated jaguars moving around the area of road that we were interested in, we found that males could cross the road in many different locations. Yet females were restricted to areas that had very low human densities."

He added that although males were more disposed to crossing the roads, it did increase the likelihood of road kills.

Using the model, the team identified a 1km stretch of road where the likelihood of both sexes crossing it were the highest. This was the location, they predicted, that would be the most suitable for the establishment of a wildlife pass under the road.

They added that using a predictive model could "greatly advance region-wide conservation plans for the location of corridors and conservation areas".

Dr Colchero added: "We applied this model to roads that already existed, but if the road does not exist then you cannot have direct information on where the animals are crossing a road.

"Our modelling can help a lot because you can simulate the road and see where animals would most likely cross.

"That is one of the main advantages of using such a method because you need to be able to do predictions and that is one of the things that current methods lack: to be able to predict where animals were most likely to cross the road."