Migrants from the Near East 'brought farming to Europe'

- Published

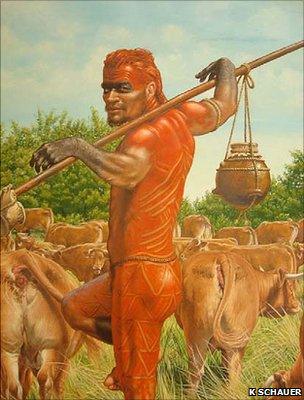

The first farmers are believed to have brought domesticated cattle with them to Europe

Farming in Europe did not just spread by word-of-mouth, but was introduced by migrants from the ancient Near East, a study suggests.

Scientists analysed DNA from the 8,000 year-old remains of early farmers found at an ancient graveyard in Germany.

They compared the genetic signatures to those of modern populations and found similarities with the DNA of people living in today's Turkey and Iraq.

The study appears in the journal PLoS Biology, external.

Wolfgang Haak of the University of Adelaide in Australia led the team of international researchers from Germany, Russia and Australia.

Up until now, many scientists believed that the concept of farming was brought to Europe merely by the transfer of ideas. They thought that European hunter-gatherers living in close proximity to ancient farmers in the Near East were spreading the information about more settled ways and agriculture further north.

But the recent study challenges that hypothesis.

"We have shown that the first farmers in Europe had a much greater genetic input from the Near East and Anatolia, than from populations of Stone Age hunter-gatherers who already existed in the area," said Dr Haak.

A co-author, Professor Alan Cooper, also of the University of Adelaide, agreed.

"This helps to overturn current thinking, which accepts that the first European farming populations were constructed largely from existing populations of hunter-gatherers, who had either rapidly learned to farm or interbred with the invaders," he said.

Common ancestors

The scientists used the most modern techniques to extract the mitochondrial DNA - genetic code that is passed down via the maternal line - from the 8,000-year-old bones of 22 people buried at a graveyard at the town of Derenburg in Saxony-Anhalt in central Germany.

Past studies had already confirmed that the remains belonged to ancient European farmers from the Early Neolithic "Linear Pottery Culture".

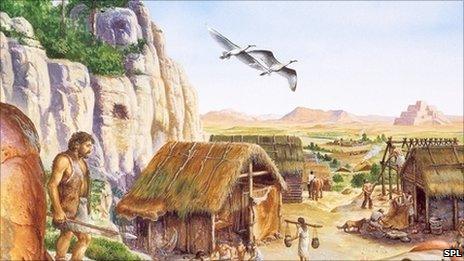

An artist's impression of what an early Neolithic settlement might have looked like, some 8,000 years ago

The researchers then compared defining DNA segments known as haplotypes with those of people living across Eurasia today.

The existence of the same haplotypes in people from different regions shows that they share a common ancestor.

And that was exactly what Dr Haak's team found.

Richard Villems from the University of Tartu and Estonian Biocentre in Estonia, a co-author of the study, called the results exciting, but said that further studies might yield even more important results.

"The ancient DNA is much better preserved in cold Europe than in warmer places," he told BBC News.

"But if it were possible, and hopefully it will be possible in the future, to match it with some 8,000-10,000 year-old samples from the Near East, then it would really be perfect."

The analysis also revealed that the hunter-gatherer population living in Europe did not die out as a result of the "invasion" of the migrants from the Near East.

Instead, the two groups mingled together, which resulted in "mixed" ancestry, signs of which the team discovered at the graveyard.

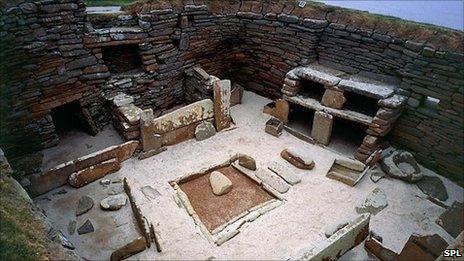

One of the houses in the Neolithic settlement at Skara Brae, in Scotland's Orkney islands

Spencer Wells, director of the Genographic Project, a large-scale genetic survey of human migration, explained to BBC News that the farmers moved via a route from the Near East and Anatolia, where farming evolved around 11,000 years ago, to south-eastern and then Central Europe.

They then continued moving further north, possibly because of climate change, mixing with the indigenous population along the way.

These conclusions, he added, are an important argument in the nearly half-century long debate about the origins of farming in Europe.

"It seems to point to a natural migration of human beings out of the Near East moving into Europe, spreading the farming culture," said Dr Wells.