Dark energy and flat Universe exposed by simple method

- Published

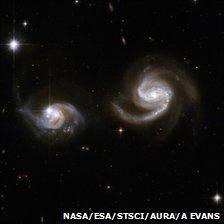

The measurement depends on hundreds of pairs of "binary galaxies"

Researchers have developed a simple technique that adds evidence to the theory that the Universe is flat.

Moreover, the method - developed by revisiting a 30-year-old idea - confirms that "dark energy" makes up nearly three-quarters of the Universe.

The research, published in Nature, external, uses existing data and relies on fewer assumptions than current approaches.

Author Christian Marinoni says the idea turns estimating the Universe's shape into "primary school" geometry.

While the idea of the Earth being flat preoccupied the first philosophers millennia ago, the question of whether the Universe itself is flat remains a debatable topic.

The degree to which the Universe is curved has an effect on what astronomers see when they look into the cosmos.

A telescope on or near Earth may see an image of a celestial object differently from how the object actually looks, because the very fabric of space and time bends the light coming from it.

Christian Marinoni and Adeline Buzzi of the University of Provence have made use of this phenomenon in their technique.

Dark prospect

The current model of cosmology holds that only 4% of what makes up our Universe is normal matter - the stuff of stars and planets with which we are familiar, and that astronomers can see directly.

The overwhelming majority of the Universe, the theory holds, is composed of dark matter and dark energy. They are "dark" because they evidently do not absorb, emit and reflect light like normal matter, making direct views impossible.

Dark energy - purported to make up 73% of the known Universe - was proposed as the source of the ongoing expansion of everything in the cosmos. Astronomers have also observed that this expansion of the Universe seems to be accelerating.

Even though gravity holds that everything should attract everything else, in every direction astronomers look there is evidence that things are in fact moving apart - with those objects further away moving faster.

Dark energy is believed to pervade the essence of space and time, forcing a kind of "anti-gravity" that fits cosmologists' equations but that is otherwise a mysterious quantity.

"The problem is that we do not see dark energy because it doesn't emit light, so we cannot measure it by designing a new machine, a new telescope," explained Professor Marinoni.

"What we have to do is to devise a new mathematical framework that allows us to dig into this mystery," he told BBC News.

Circular reasoning

The technique used in this study was first proposed in 1979 by researchers at the universities of Princeton and Berkeley in the US, external.

It relies on measuring the degree to which images of far-flung astronomical objects are a distortion of their real appearance. The authors originally suggested a spherical object would work.

The way the image is distorted should shed light on both the curvature of the Universe and the recipe of matter, dark matter and dark energy it is composed of.

The problem until now has been to choose an object whose real, local appearance can be known with certainty.

Professor Marinoni and Dr Buzzi's idea was to use a number of binary galaxies - pairs of galaxies that orbit each other.

The idea was checked using data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey

Since nature shows no preference for the direction these galaxies would be orbiting one another, a look across the whole sky should spot the full spectrum of orbital planes - up, down, left, right, side-on and so on.

Put all of them together and they should approximate a sphere.

The team formed a kind of average of all of those binary galaxies, and corrected for the varying speeds at which the galaxies might be orbiting each other.

The calculation also takes into account the relative proportion of dark energy in the Universe.

The equation was then juggled until the collection of binaries did indeed look like a uniform mix of directions.

The results suggest that the Universe is made up of about 70% dark energy.

"In general relativity, there is a direct connection between geometry and dynamics," Professor Marinoni explained, "so that once you measure the abundance of matter and energy in the Universe, you have direct information on its geometry; you can do geometry as we learn in primary school."

The team's conclusions suggest the Universe is indeed flat - an assumption first put forth by Albert Einstein and seemingly confirmed by more recent observations but that remains one of the most difficult ideas to put on solid theoretical footing.

Alan Heavens, a theoretical astrophysicist at the University of Edinburgh, said that the strength of the result lies in that it requires few assumptions about the nature of the cosmos.

"The problem that Marinoni and Buzzi have attacked is to see if we can get another, rather clean way of working out what the geometry of the Universe is without going through some fairly indirect reasoning, which is what we do at the moment," Professor Heavens told BBC News.

"They get complete consistency with [results from] existing methods, so there's nothing surprising coming out - thankfully - but it's a neat idea because it really goes rather directly from observations to conclusions."

However, while the abundance of dark energy seems on an ever-firmer footing, its nature remains a mystery.

"I don't think it can tell us in a lot of detail what the dark energy is," Professor Heavens said. "I think it's probably not precise enough - certainly not yet."