Cosmos may show echoes of events before Big Bang

- Published

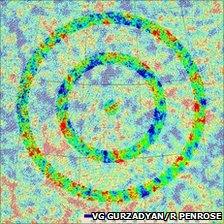

The variation in the background shifts sharply within the rings

Evidence of events that happened before the Big Bang can be seen in the glow of microwave radiation that fills the Universe, scientists have asserted.

Renowned cosmologist Roger Penrose said that analysis of this cosmic microwave background showed echoes of previous Big Bang-like events.

The events appear as "rings" around galaxy clusters in which the variation in the background is unusually low.

The unpublished research has been posted on the Arxiv, external website.

The ideas within it support a theory developed by Professor Penrose - knighted in 1994 for his services to science - that upends the widely-held "inflationary theory".

That theory holds that the Universe was shaped by an unthinkably large and fast expansion from a single point.

Much of high-energy physics research aims to elucidate how the laws of nature evolved during the fleeting first instants of the Universe's being.

"I was never in favour of it, even from the start," said Professor Penrose.

"But if you're not accepting inflation, you've got to have something else which does what inflation does," he explained to BBC News.

"In the scheme that I'm proposing, you have an exponential expansion but it's not in our aeon - I use the term to describe [the period] from our Big Bang until the remote future.

"I claim that this aeon is one of a succession of such things, where the remote future of the previous aeons somehow becomes the Big Bang of our aeon."

This "conformal cyclic cosmology" (CCC) that Professor Penrose advocates allows that the laws of nature may evolve with time, but precludes the need to institute a theoretical beginning to the Universe.

Supermassive find

Professor Penrose, of Oxford University, and his colleague Vahe Gurzadyan of Yerevan State University in Armenia, have now found what they believe is evidence of events that predate the Big Bang, and that support CCC.

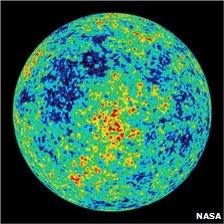

They looked at data from vast surveys of the cosmic microwave background - the constant, nearly uniform low-temperature glow that fills the Universe we see.

They surveyed nearly 11,000 locations, looking for directions in the sky where, at some point in the past, vast galaxies circling one another may have collided.

The supermassive black holes at their centres would have merged, turning some of their mass into tremendous bursts of energy.

The microwave background has, on average, only minor variations

The CCC theory holds that the same object may have undergone the same processes more than once in history, and each would have sent a "shockwave" of energy propagating outward.

The search turned up 12 candidates that showed concentric circles consistent with the idea - some with as many as five rings, representing five massive events coming from the same object through the course of history.

The suggestion is that the rings - representing unexpected order in a vast sky of disorder - represent pre-Big Bang events, toward the end of the last "aeon".

"Inflation [theory] is supposed to have ironed all of these irregularities out," said Professor Penrose.

"How do you suddenly get something that is making these whacking big explosions just before inflation turns off? To my way of thinking that's pretty hard to make sense of."

Shaun Cole of the University of Durham's computational cosmology group, called the research "impressive".

"It's a revolutionary theory and here there appears to be some data that supports it," he told BBC News.

"In the standard Big Bang model, there's nothing cyclic; it has a beginning and it has no end.

"The philosophical question that's sensible to ask is 'what came before the Big Bang?'; and what they're striving for here is to do away with that 'there's nothing before' answer by making it cyclical."

Professor Cole said he was surprised that the statistical variation in the microwave background data was the most obvious signature of what could be such a revolutionary idea, however.

"It's not clear from their theory that they have a complete model of the fluctuations, but is that the only thing that should be going on?

"There are other things that could be going on in the last part of the previous aeon; why don't they show even greater imprints?"

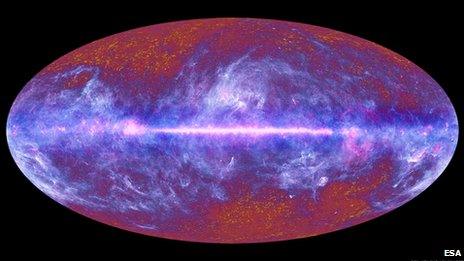

Professors Penrose and Cole both say that the idea should be shored up by further analyses of this type, in particular with data that will soon be available from the Planck telescope, designed to study the microwave background with unprecedented precision.

Planck will provide a plethora of data that may prove or disprove the idea