Africa 'can feed itself in a generation'

- Published

The new study says Africa could become a major exporter if leaders show political will

A new book claims Africa could feed itself within a generation, and become a major agricultural exporter.

The book, The New Harvest, by Harvard University professor Calestous Juma, calls on African leaders to make agricultural expansion central to all decision-making.

Improvements in infrastructure, mechanisation and GM crops could vastly increase production, he claims.

The findings are being presented to African leaders in Tanzania today.

The presidents of Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi are holding an informal summit to discuss African food security and climate change.

Speaking to the BBC ahead of the meeting, Professor Juma said African leaders had to recognise that "agriculture and economy for Africa are one and the same".

"It is the responsibility of an African president to modernise the economy and that means essentially starting with the modernisation of agriculture," he said.

Stagnation

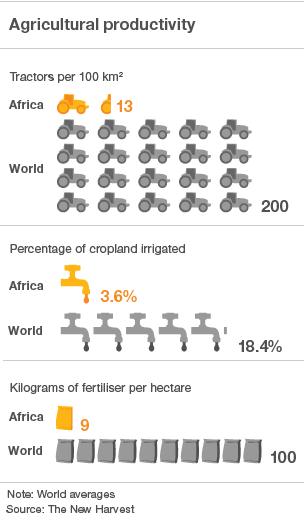

Global food production has rocketed in recent decades but has stagnated in many parts of Africa, despite the continent having "abundant" arable land and labour, says Professor Juma.

He estimates that while food production has grown globally by 145% over the past 40 years, African food production has fallen by 10% since 1960, which he attributes to low investment.

While 70% of Africans may be engaged in farming, those who are undernourished on the continent has risen by 100 million to 250 million since 1990, he estimates.

The professor's blueprint calls for the expansion of basic infrastructure, including new road, irrigation and energy schemes.

Farms should be mechanised, storage and processing facilities built, while biotechnology and GM crops should be used where they can bring benefits.

But what was needed above all else was the political will at the highest level.

"You can modernise agriculture in an area by simply building roads, so that you can send in seed and move out produce," he told the BBC.

"The ministers for roads are not interested in connecting rural areas, they are mostly interested in connecting urban areas. It's going to take a president to go in and say I want a link between agricultural transportation and then it will happen."

He believes there is great scope to expand crops traditionally grown in Africa, such as millet, sorghum, cassava or yams.

He sees areas where farmers will need to adapt to tackle a changing climate - cereal farmers may switch into livestock, he says, while others may chose more radical options.

"Tree crops like breadfruit, which is from the Pacific, could be introduced in Africa because trees are more resistant to climate change."

He also envisages genetic modification playing a growing role in African agriculture, with GM cotton and GM maize, which are already being grown on the continent, just the start of things to come.

"You need to be able to breed new crops and adapt them to local conditions... and that is going to force more African countries to think about new genomics techniques."

Kitchen sink

George Mukkath, director of programmes at the charity Farm Africa, welcomed the study, but said with many African states investing less than 10% of their GDP in agriculture, politicians had to "put their money where their mouths are".

"It's what we've been shouting about for several years," he said. "African productivity is low. If there's an investment then African farmers are very capable of producing enough food not only to feed themselves but also for the export market."

But Dr Steve Wiggins, a research fellow at a British think-tank, the Overseas Development Institute, said that modest practical changes were preferable to long wish-lists.

"It's perfectly possible to get Africa on a much higher growth rate but I wouldn't have such a long list of things to do, particularly if I thought it was going to pre-empt all government investment," he said. "To make a difference, you don't need to throw the kitchen sink at the problem."

He also warned that Africa's urban centres could not be ignored, not least because they provide important markets for African farmers.