Thousands of plant species 'undiscovered in cupboards'

- Published

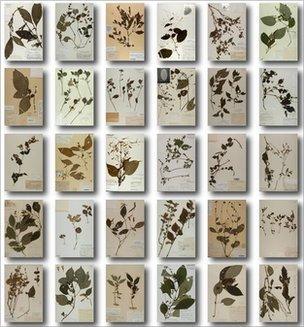

Species of Strobilanthes collected in "herbaria" and identified only decades later

More than 35,000 new species of flowering plants may be lying undiscovered in cupboards around the world, it is claimed.

Botanists looked at how long it takes for new species collected in the field to be identified, and found it often took decades.

They concluded that of the 70,000 flowering plants that experts believe are yet to be found, over half may already be in collections, awaiting identification.

The study is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences., external

Plants have been catalogued for hundreds of years. Traditionally, potential new species are dried and mounted on cardboard, labelled and placed in what is known as a herbarium for safekeeping.

There are around 3,000 herbaria worldwide, containing thousands and thousands of specimens.

Dr Robert Scotland of Oxford University spent some 15 years using these herbaria to research one particular genus of flowering plants called Strobilanthes. He found 60 new species lying undiscovered in such collections.

Together with colleagues, he decided to try and calculate how many undiscovered species of all flowering plants may be lying in such collections.

They assembled data for over 3,200 species identified since 1970 and looked at the lag between collection and identification.

They calculated that only 16% were described within five years of collection, while nearly one quarter were described over 50 years after they were first collected and placed in herbaria. One species took 210 years to be identified.

When the same pattern was projected into the future, the team concluded that over 35,000 species were likely to emerge from the herbaria collections over the next 35 years. That is half the estimated 70,000 new species of flowering plant that botanists still expect to find.

Number crunching

"We'd been doing a particular study on a group of tropical plants called Strobilanthes. It's called a monographic study when botanists look at variation in different species across the whole of the globe," Dr Scotland told the BBC.

The BBC's Neil Bowdler visits the word's largest "herbarium" at London's Kew Gardens

It is during these studies that botanists can eliminate duplications arising from different names being used for the same species in different countries, for example. But Dr Scotland's study delivered 60 new species from the depths of the herbaria collections.

"I was looking at those 60 species and what I noticed was that most of them were first collected by botanists over 60 years ago. I was quite surprised by that."

A new investigation and some number crunching led to perhaps more surprising results yet.

"What our study has shown is that only 16% of species were collected within five years of being described, whereas most get collected, they then make it into herbarium cabinets, then they sit there for up to 150 years until someone comes along and spots them."

So why are so many plants lying unidentified?

Dr Scotland puts it down to a lack of expertise and a lack of resources, but says examining these vaults may be every bit as important as future field studies.

"There are certainly places in the world which are under-collected where there's many things to be found. Botanists visit a particular rainforest, for example, and come back with a haul of species.

"[But] out of that 70,000 species still to be found, more than half of those have already been collected in the world herbaria and are waiting for someone with the relevant expertise and time to say 'that's a new one'."

Dr Mark Carine, of London's Natural History Museum and another member of the study team, said: "Lack of manpower and lack of expertise is obviously a major issue here. There's no doubt we just don't have enough people to complete the process as rapidly as we might like.

"I think what the study does is highlights the importance of collections such as the one at the Natural History Museum and elsewhere. We need to think about creative ways of unlocking information that we have in those herbaria as quickly as possible."

- Published22 September 2010