Ocean science giant Alvin set for upgrade

- Published

Few research tools in the history of science can match the achievements of Alvin, the US manned deep-submersible.

It was this 46-year-old vessel which discovered the hot volcanic vents on the ocean floor that transformed ideas about where and how life could exist.

The sub is also famed for finding an H-bomb lost at sea and for making one of the first surveys of the Titanic.

But this veteran of the abyss has been withdrawn from service this week as it gets ready for a major re-fit.

Alvin is to undergo a two-phase, $40m (£26m) upgrade that will allow it eventually to stay down longer and to go deeper - much deeper than its current 4,500m (14,800ft) limit.

"Going to 4,500m means we can dive in about 68% of the ocean," explained Susan Humprhis from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI).

"When we go to 6,500m, we will have access to 98% of the ocean. That will make a huge difference; there is so much more to see down there," she told BBC News.

Dr Humphris has been speaking here, external in San Francisco at the American Geophysical Union (AGU) Fall Meeting, the world's largest annual gathering of Earth and planetary scientists.

Alvin made its first dive in 1965. Since then it has carried some 1,400 people on more than 4,500 dives. The vessel undergoes a big service every few years, but the latest will be its most significant to date.

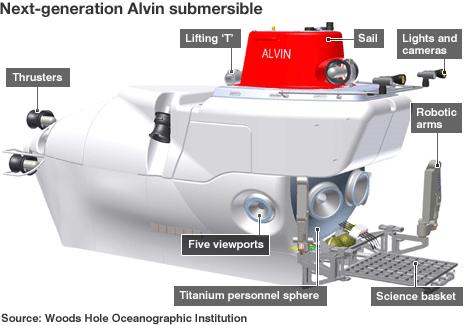

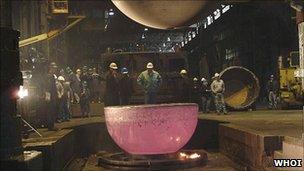

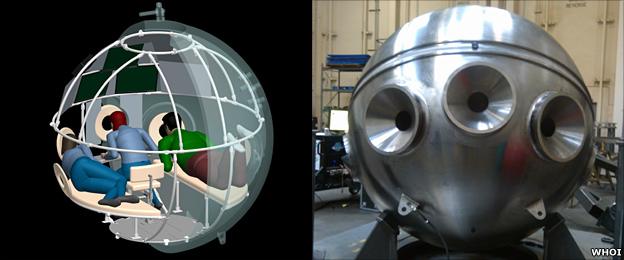

The key upgrade in the National Science Foundation-funded work will be the integration of a new $10m titanium personnel sphere - the "cockpit" in which the pilot and two research passengers sit. Forged from giant ingots weighing 15.5 tonnes, this protective ball is 16.2cm (6.4in) larger in diameter than Alvin's current sphere. Its walls are thicker, too, to cope with the greater pressures at 6,500m.

15.4 tonnes of titanium were required to make the new sphere to carry the crew

The new sphere will have five viewports instead of the existing three. These windows will provide larger and overlapping views, which will give researchers a much better idea of what is happening outside the sub.

The WHOI has brought a mock-up of the new sphere to the meeting to show the community what the finished cockpit will be like.

Other improvements in the first phase will include a new floatation foam, a new command-and-control system, better lighting and cameras, increased data-logging capabilities, and better interfaces with science instruments.

Not all its components will be changed in the first-phase re-fit, however, and it is only when all the sub's critical elements have been upgraded, including installing lithium-ion batteries for enhanced power, that Alvin will be permitted to go to 6,500m. That could be in 2015.

"People don't realise that in many ways it's a lot more difficult taking people to the bottom of the ocean than out into space," explained Dr Humphris. "When you go into space, you're going from one atmosphere of pressure to zero; when going to the bottom of the ocean, you're going from one atmosphere to 650 atmospheres. Alvin is our space shuttle, if you like."

The vessel is a research workhorse. Its final dive before the refit occurred on Tuesday when it went down into the Gulf of Mexico to inspect corals, to see how they might have been affected by the recent Deepwater Horizon oil well blowout.

Its greatest contribution to science, however, is unquestionably its discovery in 1977 of a system of hydrothermal vents off the Galapagos Islands.

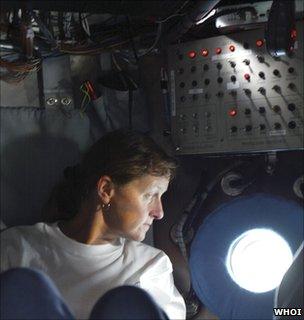

Dr Humphris says she has lost count of the number of times she has dived in the famous sub

Before its crew saw the vents' extraordinary array of animals thriving in the mineral-rich, hot waters gushing from cracks in volcanic rock, everyone assumed all the deepest places in the oceans would be like deserts - there would be no life.

Today, we know different, and at this year's AGU meeting, UK scientists have been presenting their discovery of vents at 5,000m, external, the deepest yet observed.

This system was found in waters at a location known as the Mid-Cayman Rise just south of Cuba. It was explored by robotic vehicles; the Rise is beyond the current capabilities of the manned Alvin. But one of the discoverers, Dr Bramley Murton from the National Oceanography Centre (NOC), knows Alvin from a dive he made in the vehicle 10 years ago, and said it would be "phenomenal" to take the upgraded sub to see the new the Mid-Cayman Rise system "face to face".

"These places are extraordinary," he told BBC News. "You see sights you can barely imagine - rocks covered in bacteria that fluoresce purple, green and blue, and very strange animals. It's a different world down there."

Dr Humphris said Alvin scientists often get asked - as astronauts do - to defend the value of sending people to risky places when robots could do much of this work.

"My answer to that is simple," she said. "Watch a video of the Grand Canyon and then go there yourself; then you'll realise why we go to the bottom of the ocean with human-operated vehicles. It is this question of having an eye and brain actually looking in 3D at something. I think your whole perspective changes.

"There's a big difference between looking at something on a flat-screen TV and then going down and being there, and being able to see things within their environmental context."

Peter Girguis has no doubts about the need for a human-operated vehicle. The Harvard University researcher is chair of the deep-submergence science committee.

He told reporters here: "Eighty percent of our biosphere - that is 80% of the portion of our planet that is habitable by life - is deep ocean, deeper than 1,000m.

"Everything that we typically think of, the continents and all that, is a minority. And Alvin has been enabling us to study about two-thirds of that for many years now. The Alvin upgrade promises to enable us to have a better capacity to go to deeper depths to study processes that we know are all interconnected.

"Our climate, the health of our ecosystems, the sustainability of our fisheries - all depend on processes that take place in the deep ocean."

The upgrade will start in January. When it returns to the water in 2012, Alvin will be a lot more comfortable