Shale gas: an energy saviour?

- Published

Roger Harrabin shows how to get fuel from hard rock

There's a damp chill in the Louisiana bayou as dawn casts a pink light on the swamp cypresses festooned in moss.

This is a wooded state, and timber is a steady earner for people in the countryside.

But follow the new roads snaking into the forests and you'll find a new source of wealth - brought up from nearly two and a half miles below ground.

Louisiana is cashing in on its slice of the great American boom in shale gas.

Engineers have known for decades that huge reserves of gas lay trapped tight in shale rocks - but they couldn't extract it economically.

Now that they have found a way to get it out, shale gas is being hailed as the saviour of America's energy independence.

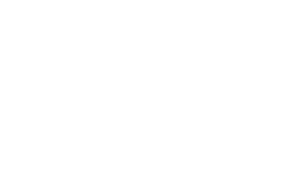

Clay metamorphises to shale under geological heat and pressure. Shale can eventually metamorphose to slate.

Over a few years since commercial operations began at scale, shale gas has helped consumer gas prices in the US to fall by about a third; it's offered gas security to the US and Canada for maybe 100 years; and it's presented an opportunity to generate electricity at half the CO2 emissions of coal.

Safety question

Shale gas has also been accused of poisoning water supplies, killing livestock, destabilising the landscape and of sucking investment from the renewable technologies said to be vital for combating climate change.

The industry vigorously denies that shale gas is unsafe - and blames pollution incidents as examples of bad practice, rather than an inherently risky technique.

And the technique of smashing the gas out of shale is certainly impressive.

Shale gas has made millionaires out of landowners in Louisiana and elsewhere

Conventional gas-bearing rocks like sandstone and limestone are porous - so if you bore into a gas-bearing seam the pressure difference brings the gas flowing to the surface.

Not shale, though. Its clay particles traps gas molecules so tight that it's been impossible to extract commercially until engineers combined existing technologies of horizontal drilling and "fracking".

I visited Shell's shale operations drilling in the Louisiana forests to see the operation first hand.

They're tapping part of the Haynesville field which has made millionaires out of landowners in Louisiana, Texas and Arkansas and has helped insulate these states from the recession. The field contains an estimated 20-30 trillion cubic feet of gas.

Phase one involves a drilling a nine-inch hole 12,382 ft down, then turning a five-inch bore horizontally for 4,389ft along the shale seam.

Once in a century

Then the rig is removed, and the frack team arrives. They feed a "perf gun" down the bore. It's a steel tube packed with a string of explosives that blow holes the width of a fine knitting needle 18 inches into the surrounding shale.

Gas is a natural by-product of shale rock

Then the perf gun is withdrawn and 16 massive trucks move in. Together they generate 7,800 psi pressure to force a mixture of fine sand, water and lubricant chemicals into the bore. The sand blasts into the piercings in the shale and jams open crevices so the gas can find its way into the bore.

Phase three is to remove almost all the equipment leaving just a few bits of kit in the cleared square in the forest. Production from this incongruously modest installation will peak over the first two years but will keep drawing out shale gas for decades.

"Shale gas is a once-in-a-century opportunity," Shell's Russ Ford told me. "It's giving north America energy security from imports, it's offering a lower-carbon fuel, and it's creating jobs." He estimates that shale will be providing 20% of US gas by 2020, and more thereafter.

But there are several controversies over environmental impacts. Some geologists fear that fracking may destabilise the ground. Then, when the drillers plunge through aquifers - water-bearing rocks supplying homes - they must seal the borehole so water doesn't leak in and waste doesn't leak out. If this isn't done right, there's trouble.

Some of the fracking water injected into the well gets absorbed by the shale. But some burps back contaminated with chemicals and has to be disposed of as hazardous.

At Shell's site in Louisiana it's injected under licence into exhausted deep gas fields sealed off from the surface by impervious layers of rock.

Methane escape

But not far from here in Shreveport cows were killed at an American firm's gas site after drinking frack water that had belched up to the surface.

Homes were evacuated when methane escaped uncontrollably from a well-head. And a documentary, Gaslands, shows extraordinary scenes of householders in New York State running taps with well water so laced with methane that they can set light to the gas in the sink.

Some of the gas operations are close to major population centres, and many people are angry that firms say the chemicals in fracking are a commercial secret. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is investigating shale gas extraction and expects to report in 2012.

Shale gas was impossible to extract until different technologies were combined

A spokesman from the US Environmental Protection agency told us: "There are serious concerns about whether the process of hydraulic fracturing impacts drinking water, human health and the environment and further study is warranted. We will make every effort to produce a final report as swiftly as possible."

The gas firms have half an eye on the electoral calendar as the head of the EPA is a political appointment. Gas states tend to be Republican whilst coal states tend to vote for Democrats. So politics might play a part in how tightly shale gas is regulated.

Shale gas is just one of three types of booming "unconventional" gas supplying America with what the gasmen call "indigenous molecules".

"Tight gas" previously trapped in sandstone can now be harvested by fracking and there's also a rush to suck methane out of coal beds.

US gas prices have dropped about 50% over the past few years, partly thanks to the recession but partly thanks to America's sigh of relief that it won't need to import much gas.

Converting terminals

Some terminals built to import liquid natural gas are now being converted to exports.

The boom in unconventional gas looks to be globally significant. With the US no longer seeking imports, the pressure is off international prices. China is also believed to have very large deposits of unconventional gas. Poland, Germany, Holland and even the UK may have commercially viable deposits.

Europe will still import gas from Russia, but every unconventional gas development erodes Moscow's role as energy superpower.

Dr Manouchehr Takin from the Centre for Global Energy Studies said: "Shale gas is definitely a phenomenon. Shale is deposited all round the world and we can expect there to be shale gas reserves in many many countries, although it's not clear yet how much will be commmercially viable.

"It will depend on how much organic material has been laid down with the shale and how much gas has already escaped. It is going to allow almost every country a degree of energy independence."

Dr Takin points out that shale gas is currently a victim of its own success, having forced down US gas prices to a point where it's no longer economic. But demand will surge back, he predicts.

The gas may have an impact on energy policies worldwide. In the UK, for instance, energy policy offers incentives for nuclear and wind to promote low-carbon growth but also to avoid dependency on "unreliable" gas supplies.

Unconventional gas is making those supplies more reliable, and some firms may press for a greater role for gas, which is more polluting than renewables but cheaper and more flexible.

The other impact may be on investment patterns. The International Energy Agency (IEA) identifies a major shortfall in capital for renewables.

There is finite energy cash globally, and some big firms seeking assured profits are already switching their investment from offshore wind farms - untested in the long term - to those familiar hydrocarbon molecules emerging from unfamiliar places.

- Published24 September 2010

- Published24 September 2010

- Published8 September 2010