Painting a suspect's portrait with DNA

- Published

DNA could be used to predict aspects of appearance, such as a person's hair and skin colour

Police sketches are a standard part of detective work, particularly in violent crimes.

A sketch or e-fit based on an eyewitness description, together with information about height, build, age and ethnicity can help lead police to a suspect.

But how many of these details could be obtained from blood or DNA left at a crime scene?

Predicting a person's outward traits from genetic information is a newly emerging field in forensics. Scientists have already developed ways of testing for traits such as age and eye colour and are working on others for skin colour and even facial dimensions.

This research effort could yield new tools to help identify unknown DNA profiles at crime scenes.

The current approach, known as genetic profiling, involves comparing crime scene DNA with that from a suspect or with a profile stored in a database.

But as Manfred Kayser from Erasmus University in Rotterdam points out, the person either needs to be among a pool of suspects identified by the police or have their profile in a DNA database.

"If both are not true, you can have the nicest DNA profile in the world but you cannot do anything with it," he told BBC News.

'The full monty'

On Tuesday, Professor Kayser and colleagues published details of genes that predict the probable hair colour, external of an unknown individual.

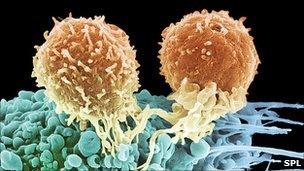

In September 2010, the Dutch researchers outlined a method for estimating the age, external of a person from blood drops. The group has also developed a test for predicting eye colour, external.

Hair colour can be predicted with a high accuracy, according to Manfred Kayser

Professor Kayser, who is chair of forensic molecular biology, external at Erasmus Medical Center, describes his team's work as "the full monty, starting from basic science up to a validated tool (test) that can applied in forensics".

Meanwhile, Mark Shriver, an anthropologist at Penn State University, external, US, has been working on the genetics of skin colour.

"We have mapped four of the major genes which determine skin colour between African and European populations," he told BBC News, adding that his group is working towards a forensic test based on the markers.

Dr Shriver says he is also working with a company on an instrument that could be used by forensic officers to test for phenotypic traits "on-site", or at a crime scene.

Facing facts

But Dr Peter Gill, a former DNA specialist at the Forensic Science Service (FSS) now based at the University of Strathclyde, external, comments: "All these markers are never definitive because they are multi-genic (determined by multiple genes).

"So you have to put a probabilistic estimate on what the presence of a gene means."

Dr Shriver is helping develop a DNA testing instrument that can be used at a crime scene

One of the most intriguing - and challenging - areas of research into phenotypic markers concerns the genes that determine the shape of a person's face.

"There are some candidates, but it's quite questionable how good these candidates are. The knowledge is very limited," Professor Kayser told BBC News.

One way Professor Kayser and his colleagues are searching for these candidates is by studying the genetics of disorders that affect the face. Scientists can then study the influence those same genes have on normal facial variation.

Another approach, he says, is to search the genome for small variations that occur more frequently in people with particular facial types. This type of search is known as a genome-wide association study.

Mark Shriver is also working on the genetics of facial proportions and has uncovered candidate genes. His work, which is being prepared for publication, suggests that single genes can exert a strong influence on the shape of the face.

A scenario where forensic scientists extract a facial image from crime scene DNA and then match it to a passport photo remains science fiction, says Professor Kayser.

But, he says: "If you can limit a large or infinite group of people - namely everybody - to a smaller group of people, namely those who fit the appearance descriptions you can currently get out of forensic samples, you can at least concentrate some of the leads which would otherwise be 'into the blue'."

Different traits are influenced to a different degree by the environment: "Grey hair can be affected by environment, whether you spend time in the Sun can obviously affect your features; height can be affected by nutrition," Dr Gill explains.

But according to Manfred Kayser: "If you estimate heritability from twin studies, you end up with about 80% heritability [for height]. That would argue that it is strongly genetic."

Ancestry analysis provided an important lead in the Madrid bombings investigation

He adds: "It turns out that there are lots and lots of genetic factors. So far, we know of about 200, but I am pretty sure there will be more than 1,000 parts of the genome that contribute to final height."

"Therefore it's more difficult to find them all to develop the final tools with the more DNA markers they include. Perhaps we will never be able to predict from DNA height as accurately as we can for eye colour. But that needs to be seen."

Peter Gill says the available tests for appearance traits are hardly used at present: "These are small steps along the way. I think it's going to be quite a long time before we get something that can be used in anger."

Dr Gill, who, along with Sir Alec Jeffreys and Dr Dave Werrett, published the first scientific paper on applying DNA profiling to forensic science, adds: "There are certain cases where the police are absolutely desperate for any information whatsoever.

"But there may be serious limitations offered by the sample. If you are trying to do multiple tests, for example, you may simply not have enough of the sample."

Ancestral roots

He says that even when a comparative test yields no match in a database, police have other options such as familial searching. This involves looking for a close, rather than exact match, in a DNA database. Such matches can turn out to be family members of the unknown person.

Immune cells can provide information about a person's age

But information about ethnic background can also refine descriptions of an unknown person. And using DNA to extract details of a suspect's geographical ancestry has already been put to use in a number of cases.

During the investigation into the 2004 Madrid train bombings, scientists used DNA from a toothbrush to identify one of the suspects as North African, external in origin. Conventional DNA analysis later led police to a suspect, an Algerian man who is still at large.

In the case of a Louisiana serial killer, eyewitness descriptions and psychological profiling initially directed police towards a white male suspect. But when DNA from a crime scene was analysed, external using a test developed by Dr Shriver, the results showed the killer was probably African-American.

While ancestry testing can be an important tool, researchers say its limitations must be recognised.

Manfred Kayser says ancestry markers can - at best - trace an individual to a broad region: "Human migration history has produced no sharp genetic borders and no sharp appearance borders," he explains.

Future benefit?

In 2009, the UK Border Agency launched a pilot scheme under which DNA from asylum seekers would be analysed, external in an effort to deduce their true nationality and curb bogus asylum claims.

The project drew criticism from Sir Alec Jeffreys, external, who called the proposal "naïve and scientifically flawed".

At the time, the Home Office responded that DNA testing would not be used alone but would be combined with language analysis and investigative interviewing techniques.

Overall, Mark Shriver says he is encouraged about the future for phenotypic testing: "I definitely think there are a lot of cases that could be assisted by this kind of information.

"It's a shame there isn't more support for this type of work," he adds, citing profit margins as one of the major reasons.

He adds: "There's the chance to make this huge contribution, protecting people who will be killed if this person continues on their path."

- Published4 January 2011

- Published14 December 2010

- Published23 November 2010

- Published5 August 2010