Birth and death within Andromeda

- Published

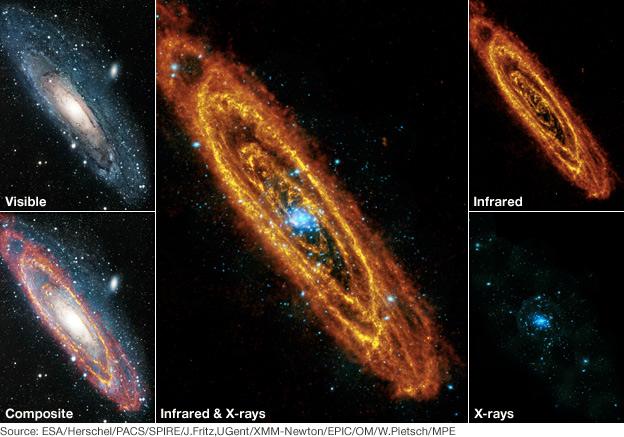

The great life cycle of stars, from the moment they switch on to the point they destroy themselves, is caught in a new view of the Andromeda Galaxy.

This picture, released to the BBC, combines the power of Europe's Herschel and XMM-Newton space telescopes.

Herschel is sensitive to infrared light and sees the cold clouds of gas and dust where stars are forming.

XMM-Newton, on the other hand, sees X-rays, a signature of the violent cosmos and the death throes of stars.

Acquired in just the past few weeks, the joint observation from the two European Space Agency (Esa) telescopes has been featured on the BBC's Stargazing Live series.

Andromeda is something of a twin to our own Galaxy, the Milky Way. It is part of the Local Group and is a mere 2.5 million light-years distant. Like the Milky Way, it is also a spiral galaxy.

Studying Andromeda is therefore seen as an excellent way to unravel some of the mysteries of our own stellar neighbourhood; and using Herschel and XMM-Newton in combination makes for a powerful probe.

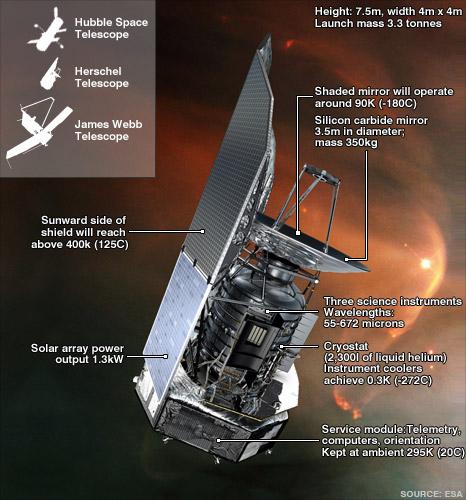

Herschel is Europe's new flagship space observatory. The billion-euro mission was launched in 2009 and carries a 3.5m-diameter mirror, the biggest ever sent into space.

A similar Herschel and XMM combination has been made of the famous Whirlpool Galaxy

Its goal is to study the processes at play in the formation of stars and the evolution of galaxies. Its detectors can pick up the light coming from the frigid clouds of gas and dust that are being warmed by the brilliant newborn stars buried within them.

This is long wavelength light, beyond the detection of our eyes or a telescope like Hubble. It is in the far-infrared.

The Herschel portion of the composite image - the yellow/orange colour - reveals in intricate detail at least five concentric rings of star-forming dust. These rings span tens of thousands of light-years across.

"It is the first time we have been able to achieve such resolution," said Dr Jacopo Fritz from Ghent University, Belgium, external, who led the Herschel observation.

"Normally, if you take images at longer wavelengths, like the infrared, the spatial resolution gets worse; it's an intrinsic property of the light itself. But if you increase the size of the mirror, like the one we have on Herschel, then your spatial resolution increases; and we've never seen galaxies [in the infrared] with such high resolution as this before."

XMM-Newton is Europe's orbiting X-ray telescope. It was launched in 1999

XMM-Newton, in contrast, is a veteran space observatory having already celebrated a decade in orbit.

Its detectors are tuned to much shorter wavelengths of light which betray very different processes.

The violence of stars blowing themselves apart, or gas being torn to shreds as it is pulled into a black hole, will produce copious X-rays. This is what XMM-Newton sees.

An artist's impression of a neutron star pulling gas off a normal companion star

The XMM-Newton portion of the image (dominated by the blue colour) shows hundreds of X-ray sources within Andromeda, many of them clustered around the centre where the stars are densest.

Some of the X-ray emission will be coming from locations where the gravity from aged stars, known as white dwarfs, is pulling gas from larger companion stars.

In these systems the white dwarfs may eventually grow massive enough to collapse catastrophically and explode as supernovas. Other X-rays will be coming from locations where long-dead, super-dense stars - known as neutron stars - and even black holes are also stealing material from nearby normal stars.

It is all part of a grand cycle that turns over the course of billions of years.

As stars explode they disperse gas and dust across the galaxy. The shockwaves from these explosions will also perturb this and other material, triggering the gravitational collapse of these clouds and the formation of yet more stars.

"You see a dynamic, living galaxy," said Dr Mark Kidger from Esa's Space Astronomy Centre in Madrid, Spain. "You see the stars forming where it's brightest yellow, and the blue patches are where stars are dying."

The image at the top of this page includes a visible, or optical, view of Andromeda. This top-left window is a Hubble picture, external and the type of view we would have with our own eyes.

The Herschel telescope has to be kept extremely cold to study its frigid targets

- Published1 September 2010

- Published1 July 2010