Gulf of Mexico oil leak may give Arctic climate clues

- Published

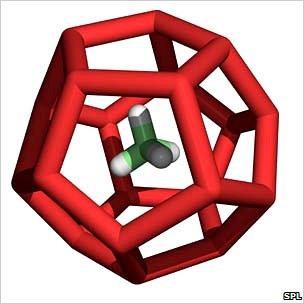

Vast amounts of methane are present in the Arctic, often in the form of hydrates

Almost all of the methane released in the Gulf of Mexico oil leak was quickly swallowed by bacteria - which may give clues to climate change in the Arctic.

Writing in journal Science, US researchers report that methane-absorbing bacteria multiplied in the Gulf following the April accident.

The Arctic contains vast stores of methane, and its release could quickly accelerate warming around the world.

But scientists caution that the regions are very different.

The research ship Pisces, operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa), made several voyages into the Gulf in the months following the leak.

"There were thousands of different types of molecule coming out of the well, and by far the most abundant was methane," said research leader John Kessler, from Texas A and M University.

"In fact, by weight, 30% of it was methane.

"Normally we have to go around and study what's seeping naturally out of the sea floor; but this release was massive and localised."

Virtually all of the methane remained suspended and dissolved in sea water at depths of around one kilometre.

Bacteria in the water that have evolved to process naturally-seeping methane apparently increased in number, taking oxygen from the water as they did so, and mopping up the Deepwater Horizon's cargo.

The team's calculations indicate that less than one hundred thousandth of the gas released made it into the atmosphere.

Warming warning

Methane is the second most important gaseous component of the man-made portion of the greenhouse effect.

The Gulf waters were sampled for methane

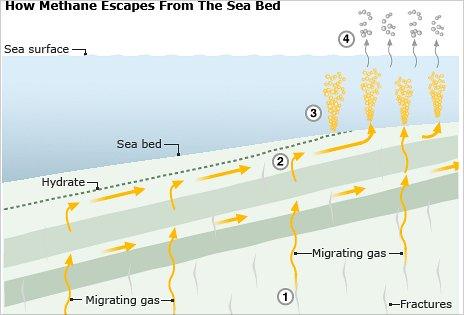

And vast quantities of it - no-one knows how much, though some estimates put it as 3,000 times the current amount in the atmosphere - lie trapped in the sea bed around the Arctic. There are other deposits around the world as well.

Some see this methane hydrate as a potential future energy source.

Others fear that if it escapes as the seas warm, it will act to amplify global warming.

In principle, the Deepwater Horizon research could help inform scientists about how serious methane releases could be - how much would be processed in sea water, and how much would make it into the atmosphere.

"In the Arctic, there definitely would be some sort of microbial response; and in most places on the sea floor that have the capacity for massive release, there will be some seepage that will help to populate the water with microbes that could respond," Dr Kessler told BBC News.

However, he cautioned, there are big differences between the Gulf of Mexico leak and potential methane sources in the Arctic.

Ed Dlugokencky, who runs Noaa's global registry of methane concentrations but was not involved in the Gulf research, agreed.

"The implications of this work for release of methane from hydrates likely only applies to deep waters, not areas where hydrates exist on shallow continental shelves such as the East Siberian Arctic shelf," he said.

"There, water is only about 40m deep, and bubbling is an important mechanism for transport of methane from the sediments to the atmosphere."

The shallower the water, the less time methane would spend in it, making absorption less likely. Temperature, currents and the types of bacteria present could be other factors important in determining how much makes it into the atmosphere.

However, Dr Dlugokencky noted that evidence of vast, rapid releases of methane from the sea floor has not been seen in ice-core records, which now trace Earth history back about 800,000 years.

Methane can escape from hydrates on or under the sea bed, and bubble to the surface; higher temperatures may exacerbate the problem

Research ships make regular cruises to the Arctic and have regularly found evidence of methane bubbling into the atmopshere.

But, said Professor Graham Westbrook from the UK's University of Birmingham, there is still a lot of basic science to be done.

"We don't know the distribution of the methane hydrates - we don't know how pervasive they are in the region," he said.

"And in places like the shelf areas north of Siberia, where releases have been found, it's not clear how much of this is coming from the sea bed and how much is brought into the sea by rivers.

"Also, we don't know how much of the releases we see are down to anthropogenic warming in the last couple of centuries, and how much relates to the natural warming we've seen since the end of the last Ice Age."

- Published6 January 2011