Planck telescope observes cosmic giants

- Published

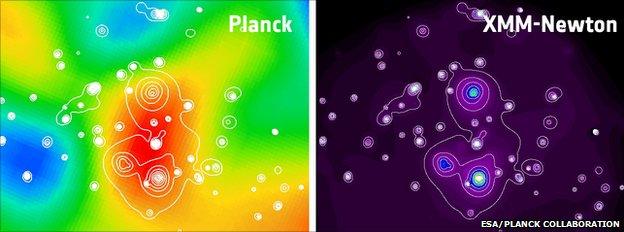

A supercluster of galaxies as it appears in Planck data (l) and in XMM data (r). Such structures contain hundreds of billions of suns

The Planck space telescope has identified some of the largest structures ever seen in the Universe.

These are clusters of galaxies that are gravitationally bound to each other and which measure tens of millions of light-years across.

Astronomers say the Planck observatory has made more than 20 detections that are brand new to science.

The European Space Agency telescope has also confirmed the existence of a further 169 galaxy clusters.

Follow-up studies have hinted at the great scale of these structures.

"The clusters contain up to a hundred galaxies, and each galaxy has a billion stars," said Dr Nabila Aghanim of the Institut d'Astrophysique Spatiale in Orsay, France.

The clusters, sighted in all directions, range out to about four billion light-years from Earth.

Astronomers are interested in such observations because they say something about the way the Universe is built on the grandest scales - how matter is organised into vast filaments and sheets and separated by great voids.

Not only do the clusters contain colossal quantities of visible matter - stars, gas and dust - but they also retain even larger quantities of invisible, and as yet unidentifiable, "dark matter".

Planck made the discoveries during its on-going survey of the "oldest light" in the cosmos.

This relic radiation from the Big Bang 13.7 billion years ago fills the entire sky in the microwave portion of the electromagnetic spectrum.

It is referred to famously as the Cosmic Microwave Background, or simply the CMB.

Planck's ultra-precise recording of this light should provide remarkable new insights on the age, contents and shape of the Universe.

Scientists hope the telescope's imagery can also prove the theory of "inflation", an idea that the cosmos experienced a turbo-charged, faster-than-light-expansion in its first, fleeting moments.

But to get a clear view of all this information, scientists must first subtract the light emitted by other astrophysical phenomena shining in the same frequencies.

Although regarded as "noise" in the context of Planck's main mission, this "rejected" light is still hugely valuable to scientists who study its sources - including those astronomers interested in mapping galaxy clusters.

Dr Aghanim and colleagues found these structures by looking for the so-called Sunyaev-Zel'dovich (SZ) effect in the Planck data.

Clusters are surrounded by fantastically hot gas - at many millions of degrees.

In these conditions, electrons become detached from atomic nuclei and move around at great speed.

About 1% of the particles, or photons, of CMB light moving through these structures will interact with their swarms of hot electrons.

This has the effect - the Sunyaev-Zel'dovich effect - of distorting the CMB in a very characteristic way: it becomes depleted at lower frequencies and boosted at higher frequencies.

"It's a great trick," Dr Aghanim told BBC News. "We look for spots on the sky that are less bright than average at low frequencies and then look for spots that are brighter than average at high frequencies, and if these locations match up we have our candidate clusters."

The research does not end there, however. The SZ distortions in the Planck data have to be followed up with observations from the likes of Europe's XMM-Newton space telescope.

XMM, because it is sensitive to X-ray light, can see the emission coming from the hot electrons themselves. It is independent confirmation.

Many of the Planck clusters look very disturbed objects, suggesting the telescope may be seeing these structures in the early stages of formation, says Dr Aghanim.

Information on all the Planck clusters has been made public as part of the Planck Early Release Compact Source Catalogue (ERCSC).

This is a list of some 15,000 astrophysical phenomena spied by Planck and which, again, are secondary to its main objective of detailing the CMB.

"This 'first light' we're looking for is a very faint signal that is on top of a very high level of noise," explained Planck project scientist Dr Jan Tauber.

"This noise comes from the rest of the Universe - our galaxy, other galaxies and clusters of galaxies. In order to get to the CMB, we first have to understand everything else because if we cannot get rid of it accurately, we cannot be sure what we're measuring in the early Universe is what we really want to see," he told BBC News.

Planck will continue to scan the sky until at least the end of 2011, certainly enough for five-times coverage.

The Planck Scientific Consortium will then need some time to analyse all the data and assess its significance.

A formal release of fully prepared CMB images and scientific papers is not expected before January 2013.

Planck is a flagship mission of Esa. It was launched in May 2009 and sits more than a million km from Earth on its "night side".

It carries two instruments that observe the sky across nine frequency bands.

The High Frequency Instrument (HFI) operates between 100 and 857 GHz (wavelengths of 3mm to 0.35mm), and the Low Frequency Instrument (LFI) operates between 30 and 70 GHz (wavelengths of 10mm to 4mm).

Planck's view of the entire sky: Ultimately, scientists must remove all the foreground "noise" (blue) to get a clear view of the CMB (magenta and yellow)

- Published26 December 2010