What freediving does to the body

- Published

With sea levels rising, can humans adapt to a more watery world? The Bajau people of South-East Asia live in stilt houses and fish underwater for up to five minutes on one breath. What does this do to the body?

Take a deep breath in - how long until the urge to gasp for air becomes too much? Perhaps it comes after 30 or 40 seconds.

But the bodies of habitual freedivers, who hold their breath for minutes at a time, can change to be better adapted to the water.

The Bajau people, sometimes known as the sea gypsies of Malaysia and Indonesia, are renowned natural freedivers. Traditionally, they are born, live and die at sea, and fish by diving 20m (more than 65ft) underwater for minutes at a time on one breath.

At this depth, water pressure is almost three times what it is on the surface, squeezing lungs already deprived of oxygen.

Filmed underwater in real time for the BBC's Human Planet, Bajau fisherman Sulbin demonstrates his techniques off the east coast of Sabah, Borneo. Wearing hand-made wooden goggles and armed with a spear, he first prepares himself mentally.

"I focus my mind on breathing. I only dive once I'm totally relaxed," says Sulbin, who goes into a trance-like state before entering the water.

This degree of mind control is crucial, says freediving instructor Emma Farrell, the author of One Breath, A Reflection on Freediving. "You have to be warm and relaxed - you don't want to hyperventilate before taking your last breath."

A Bajau stilt village, built on a coral reef - some settlements are far off shore

The mammalian dive reflex - seen in aquatic animals such as dolphins and otters, and in humans to a lesser extent - helps, says Farrell.

"It's a series of automatic adjustments we make when submerged in cold water. It reduces the heart rate and metabolism to slow the rate you use oxygen."

During breath-holding, oxygen stores reduce and the body starts diverting blood from hands and feet to the vital organs.

Our bodies have a way to compensate. Underwater pressure constricts the spleen, squeezing out extra haemoglobin, the protein in red corpuscles that carry oxygen around the body.

"Not enough research has been done to know if it wears off when you're not diving," says Farrell. "But I know people who do a lot of deep training - as Sulbin does - whose blood is like that of people living at high altitude."

In high altitudes, there is less oxygen and so the amount of haemoglobin in blood increases.

Seeing underwater

For most of their history, the Bajau have lived on houseboats, or in stilt houses built on coral reefs - some far from shore. Many report feeling "landsick" on the rare occasions they spend time on dry land.

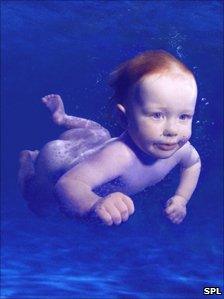

Our dive reflex means babies don't breathe in underwater

Thanks to time spent in the water as children when the eyes are developing, the Bajau, in common with other coastal dwelling people, have unusually strong underwater vision.

Their eye muscles have adapted to constrict the pupils more, and to change the lens shape to increase light refraction.

This makes their underwater eyesight twice as strong, according to Anna Gislen, of Sweden's Lund University, who from 2003 has compared the water vision of sea gypsy children of Thailand and Burma with that of European children. A gap that can narrow with training.

One part of the Bajau body that hasn't fared well is the eardrum, which ruptures at a young age, says Human Planet director Tom Hugh-Jones.

"Sulbin's hearing is shot because he doesn't equalise the pressure in his ears as he dives. He's never had formal dive training. He was taught by his father to hold his breath."

There are evolutionary theories - not widely accepted, he adds - that an early ancestor of modern humans had to adapt to a partially aquatic environment. The aquatic ape theory suggests this is why humans are largely hairless and have a subcutaneous layer of fat for underwater insulation, and so are better adapted to swimming than near relations such as the great ape.

Bajau children's underwater vision is less blurred than landlubbers of the same age

But Sulbin and other Bajau divers have little body fat. The wiry frame of these subsistence fishermen may actually help.

A lean physique is more efficient at using oxygen. And having little body fat makes Sulbin less buoyant, able to walk across the reef bed with ease.

"This type of freediving - repeatedly diving to depths of 10 to 20m - carries the greatest risk of decompression sickness," says Farrell. "But you are less likely to get the bends if you are lean, or very well hydrated."

Some Bajau die of the bends from diving - also a risk for compression divers in the Philippines encountered by the Human Planet team.

"Anyone who thinks this is an example of what a non-smoker's lungs can do will be disappointed," says Hugh-Jones. "Sulbin smokes like a chimney. He says it relaxes his chest."

Human Planet will be broadcast on Thursday 13 January at 2000 GMT on BBC One, and will also be available on the BBC iPlayer.