Sofia flying telescope gives unique view of Orion

- Published

The Orion nebula is an important star-forming region

A telescope in the back of a modified 747 jet has snapped images of the Orion Nebula at a colour of light no other observatory in the world can see.

They are the first results from the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (Sofia), designed to capture colours blocked by Earth's atmosphere.

The images show the star-forming region in unprecedented clarity.

Further study could yield insight into stars that are just lighting up, one of astronomy's "holy grails".

The results were presented at the American Astronomical Society's annual meeting, external in Seattle, US.

Sofia is a successor to the Kuiper Airborne Observatory (KAO), which was retired in 1995.

The long-delayed Sofia project is now picking up where the KAO left off - allowing astronomers to see light at colours deep in the infrared.

Space telescopes can see out in this part of the spectrum as well, but Sofia allows far more flexibility.

Beyond the dust

"The real unique thing is that you have a platform you can change out instruments on," said Terry Herter, an astronomer at the University of Cornell, and lead scientist on Sofia's first science mission known as Forcast (Faint Object Infrared Camera for the Sofia Telescope).

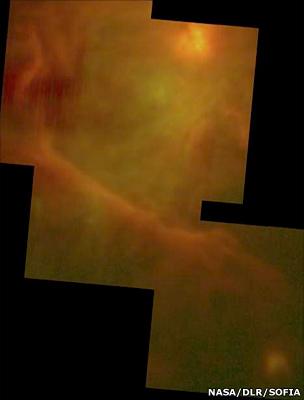

The airborne observatory can view light in the deep infrared

"To do this part of the spectrum you need either to go to space or you need to use balloons or an airborne observatory."

Balloons have proven difficult to control, and to change anything on a space telescope, Professor Herter told the BBC, "you have to send the shuttle up to service it or you need to launch another mission".

The observatory captured its first image in May 2010, and in November flew its first science mission, peering into the Orion Nebula through the dense clouds of dust that obscure the image in colours of light that we can see.

"There's a set of stars in there that are very newly born," Professor Herter said.

"The holy grail of astronomy has always been to find stars just turning on. One of the things we can do with Sofia is look in detail at the earliest generations of stars."

The largest stars in such regions drive much of the stellar formation in their neighbourhood, but only live for a few million years, and Professor Herter said Sofia would allow a unique opportunity to study them.

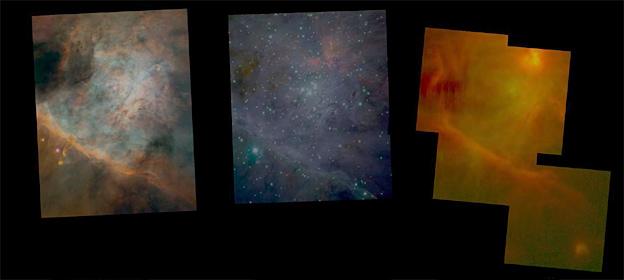

Sofia's mid-infrared view of the Orion Nebula compared with the views of the Hubble Space Telescope (left - at visible wavelengths) and the European Southern Observatory (middle - at near-infrared wavelengths)

The fact that the telescope is mounted in a plane presents a set of unique challenges to astronomers.

The telescope is gyro-stabilised, so that even though the plane is moving, the telescope stays pointing fixedly at its target.

But just how fixedly it could point "was a question mark", said James De Buizer of the Universities Space Research Association, which runs Sofia for Nasa.

"You can do all the simulations you want, and wind tunnel experiments of scale models," Dr De Buizer told BBC News, "you still don't know what the actual image quality of a telescope is going to be when it's in the back of a plane going at Mach 0.9 with wind whipping through there."

"But right out of the box, without most of the motion compensation equipment turned on, we were getting image qualities that were pretty close to the best you can get for a telescope of that size."

Sofia's mission is only just beginning in terms of science, but has already been down a long road of development.

The observatory was initially planned to fly in 1998, just three years after the KAO was retired.

But budget and timeline over-runs delayed the project time and again.

"I think Sofia has turned quite a corner in its history," Dr De Buizer said.

"It was cancelled in 2006 as a Nasa programme, later reinstated, and now the astronomy division of Nasa has two top priorities - one is the James Webb Space Telescope and the other is Sofia."