Amoebas show primitive farming behaviour as they travel

- Published

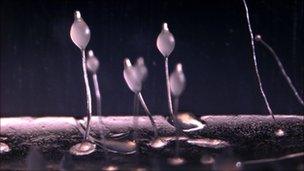

The amoeba is known to gather together in large "fruiting bodies"

A species of amoeba - among the simplest life forms on Earth - has been seen "farming" the bacteria it eats.

When the bacteria become scarce, the Dictyostelium discoideum slime mould gathers up into a "fruiting body" that disperses spores to a new area.

Research described in Nature, external shows that a third of these spores contain some of the bacteria to grow at the new site.

Food management has been seen in animals including ants and snails, but never in creatures as simple as these.

The behaviour falls short of the kind of "farming" that more advanced animals do; ants, for example, nurture a single fungus species that no longer exists in the wild.

But the idea that an amoeba that spends much of its life as a single-celled organism could hold short of consuming a food supply before decamping is an astonishing one.

More than just a snack for the journey of dispersal, the idea is that the bacteria that travel with the spores can "seed" a new bacterial colony, and thus a food source in case the new locale should be lacking in bacteria.

D. discoideum is already something of a famous creature, having proven its "social" nature as it gathers together into a mobile, multicellular structure in which a fifth of the individuals die, to the benefit of the ones that make it into the fruiting body.

Researchers from Rice University in Texas, looking to study the amoebas further, happened across another, truly unique behaviour - discovered perhaps because the samples came from the wild, rather than grown in the laboratory.

"It was a bit of serendipty, really," Debra Brock, lead author of the Nature story, told BBC News.

"I had previously worked with them, looking at developmental genes. Not many people work with wild clones but I had started in a new lab and my advisers had a large collection of them, and I came with a bit of a different perspective."

Costly choice

Once Ms Brock spotted the amoebas' fruiting bodies carrying bacteria, she measured how many of the spores were responsible, finding that about a third of them traveled with their bacterial seeds.

The behaviour seems to be genetically built-in; clones of the "farmer" amoebas in turn developed into farmers, while clones of the "non-farmers" did not.

The bacteria form the basis of a food crop at the spores' new locations

"To think of a single-celled amoeba performing something that you could consider farming, I think, is surprising," Ms Brock said.

"Choices like that are generally costly, so there has to be a pretty large benefit for it to persist in nature."

That is to say, the amoebas, in choosing not to consume all of the bacteria around them, are forced to make smaller fruiting bodies that cannot travel as far when they disperse.

There is thus an evolutionary balance to be struck between the advantage gained by showing up with the beginnings of a crop and the cost of bringing it.

Jacobus Boomsma of the University of Copenhagen said that the find was a surprising one, and gives insight that has been absent in farming creatures known already to science.

For example, all the individuals of a given ant or termite species farm particular species of fungus exclusively, and the "free" versions of the advanced farmed fungi no longer exist.

"Here, farming and non-farming [members of the species] coexist, so they look perfectly normal until you put them under the microscope and know what you're looking at; [the bacteria] don't assume specialisesd roles as crops like fungi that ants and termites rear," Professor Boomsma told BBC News.

"In other farming systems that we see, they always lack this intermediate stage."

Ms Brock said that further study has already found other species of amoeba that "pack a lunch", and that D. discoideum carries more than just a snack.

"Bacteria generally provide huge resources that are really untapped," Ms Brock said.

"These amoebas carry bacteria that aren't just used for food, so that's what I'm looking into now."