Q&A: Challenger shuttle disaster

- Published

On 28 January 1986, the space shuttle Challenger disintegrated 73 seconds after launch, claiming the lives of seven astronauts.

On the 25th anniversary of the disaster, science reporter Paul Rincon looks back at the events which led up to the accident and its impact on human spaceflight.

How did the accident unfold?

The seven astronauts of the space shuttle Challenger were to have spent six-and-a-half days in Earth orbit, during which they would have deployed a satellite and carried out a number of experiments.

One of the crew members, Christa McAuliffe, was to have been the first teacher in space - selected from more than 11,000 applicants under a programme announced by US President Ronald Reagan.

After several launch delays, Challenger lifted off from Florida's Kennedy Space Center at 1138 local time on 28 January. In the first few seconds after lift-off, cameras captured several puffs of dark smoke emerging from a joint in the shuttle's right booster rocket.

About 37 seconds into the flight, Challenger began experiencing severe wind shear conditions - changes in the direction and speed of the wind - which exerted strong forces on the vehicle.

Challenger's ill-fated 10th flight

The first flickers of flame from the rocket booster joint emerged 58 seconds into the launch. And these swiftly expanded into a well-defined orange plume. A few seconds later, the shape and colour of the plume changed as the flame pierced the shuttle's huge external tank and began mixing with the hydrogen fuel leaking out.

Some 73 seconds into the 25th US shuttle flight, the external tank tore apart, forming a vast fireball 14km (46,000ft) up as hydrogen and oxygen fuel escaped into the atmosphere. The Challenger shuttle was ripped apart by aerodynamic forces as it was cut loose from the external tank. There were no survivors.

What happened next?

Millions of people following coverage of the launch watched in horror as the vehicle broke apart in mid-air. Within minutes of the disaster, ships and aircraft were despatched to begin the recovery effort in the Atlantic waters where debris fell.

President Ronald Reagan had been due to give the annual State of the Union Address on the evening of the Challenger accident. Instead, he postponed this by a week and gave a televised address to the nation in which he paid tribute to the astronauts.

The speech concludes with President Reagan quoting from the poem High Flight by John Gillespie Magee Jr: "We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for the journey and waved goodbye and 'slipped the surly bonds of Earth' to 'touch the face of God'."

President Reagan - who was said to have been personally affected by the disaster - set up an independent commission to probe the probable cause of the disaster.

On 7 March 1986, a US Navy ship identified the remains of Challenger's crew compartment, sitting largely intact on the ocean floor. Divers were sent to recover the cabin, along with the remains of the crew members. Funeral ceremonies were held for the astronauts over April and May.

Who were the Challenger astronauts?

In 1984, Boston-born Christa McAuliffe was chosen to make the first flight under the Teacher In Space Project, turning her into a celebrity overnight. She was to have carried out two 15-minute lessons from space to be broadcast to schoolchildren. McAuliffe's presence on the shuttle had already raised the profile of this mission in the minds of the public and the media.

The shuttle's commander Francis "Dick" Scobee was a former US Air Force pilot who had flown on Challenger once before. Challenger's pilot Mike Smith had flown attack aircraft during the Vietnam war, but this was his first shuttle flight.

Judith Resnik - a "mission specialist" on Challenger - was an electrical engineer signed up to the astronaut corps in 1978 by Nichelle Nichols - the actress best known for playing Uhura in Star Trek - when Nichols had been working as a recruiter for Nasa. Ms Resnik's group of astronaut trainees was the first to include women.

Mission specialist Ron McNair, from South Carolina, was a Massachusetts Institute of Technology-educated physicist with a black belt in karate. He was one of the first African-Americans recruited into Nasa's astronaut corps and, like Dick Scobee, had flown on Challenger before.

The third mission specialist, Ellison Onizuka, was previously an engineer with the US Air Force and had flown in space once before. Onizuka's background made him a natural choice to fly on the first classified military space shuttle flight in 1985.

Ms McAuliffe was not the only civilian on Challenger. Payload specialist Gregory Jarvis worked for the Hughes Aircraft Corp in Los Angeles. Mr Jarvis was accepted into the astronaut programme under the Hughes company's sponsorship after competing against 600 other employees for the opportunity.

What were the causes of the disaster?

The independent commission set up to investigate the disaster was headed by the former Secretary of State William P Rogers. Among the members were Neil Armstrong, the first man on the Moon; Sally Ride, the first American woman in space; Chuck Yeager, the test pilot; and Richard Feynman, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist.

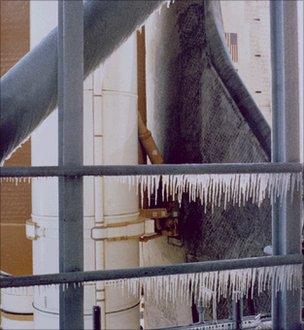

Unusually cold conditions prior to launch may have affected seals on the booster rockets

The Rogers Commission released its report, external in June 1986, concluding that the destruction of Challenger had been caused by the failure of the joint in the two lower segments of the shuttle's right solid rocket booster.

More specifically, the failure happened because of the destruction of the "O ring" seals intended to prevent hot gases leaking through the joint while the rocket propellant was burnt during flight.

The commission found that a contributing factor had been the unusually cold temperatures at Cape Canaveral prior to the launch, which had caused the rubber O ring to become significantly less elastic. Richard Feynman memorably demonstrated this effect on television by dipping a sample of the material in ice water to show how it became less pliable.

"I discovered that when you put some pressure on it and then undo it, it doesn't stretch back. It stays the same dimensions for a few seconds at least," Feynman said during one of the commission hearings.

"There's no resilience in this particular material when it's at 32 degrees (F). I believe that has some significance for our problem."

It emerged during the investigation that engineers at Nasa and the booster rocket contractor Morton Thiokol were well aware of flaws with the O ring seals.

The report concluded that Nasa's organisational culture and decision-making processes had been key contributing factors in the accident. Managers had failed to adequately communicate engineers' growing doubts about the seal to senior officials.

What was the legacy of the accident?

Among the recommendations made by the Rogers Commission were design changes to the rocket booster joints and seals.

The investigation also urged Nasa to establish a strong and independent office to look after "safety, reliability and quality assurance". The investigation and the corrective actions undertaken by Nasa led to a 32-month hiatus in shuttle launches.

After the shuttles resumed flying in 1988, the programme continued without a serious accident until 2003, when the Columbia shuttle broke up as it tried to re-enter the atmosphere from orbit.

Nasa had made significant changes, both to its management structure and safety procedures, after the Challenger accident. Nevertheless, the accident investigation report, external for the Columbia disaster drew parallels with Challenger.

"First, despite all the post-Challenger changes at Nasa and the agencyʼs notable achievements since, the causes of the institutional failure responsible for Challenger have not been fixed," the report said.

As a result of the Columbia accident, the US space agency made many improvements to shuttle safety, including inspections for damage sustained on launch.

- Published28 January 2011

- Published28 January 2011

- Published27 January 2011