Six exoplanets in close orbit around far-flung star

- Published

David Shukman tours the lab where Kepler's sensors are made

A solar system including six planets around a star 2,000 light-years away has been spotted by astronomers.

The planets range between two and four-and-a-half times the radius of Earth, and between two and 13 times its mass.

Five of the planets orbit the star closer than Mercury orbits our Sun.

The find, published in Nature, external, is the first from the latest data release from the Kepler space telescope - which includes details of more than 1,000 additional exoplanet candidates.

The planets are likely to have atmospheres made of light gases, but also likely to be too hot to support life.

The Kepler team released the raw data that led to the discovery as part of its commitment to making its findings publicly available.

Kepler has already yielded evidence of a three-planet system, Kepler-9, external, and in January the team announced it had spotted the first definitively rocky exoplanet, Kepler-10, external.

The newly-discovered solar system, around the star Kepler 11, is a rich "laboratory" for studying planetary formation. Its surprising number of planets orbiting so closely together gives astrophysicists a unique system to refine their theories of how planets form.

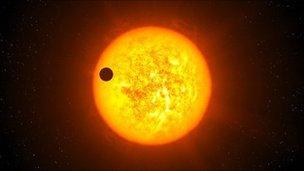

Kepler measures stars' "light curves" as planets that pass in front block some of their light

The find is different from the planetary system HD10180, first announced in August 2010, external, in which a rich exoplanet system comprising at least five planets orbits a star 127 light-years away. In that study, the "wobble" that the planets' gravity caused on their host star was used to infer their presence; a sixth and seventh planet are yet to be confirmed.

The Kepler telescope, by contrast, performs a more direct observation, measuring the minuscule dimming that occurs when planets pass in front of their host star.

Typically, in these "transit" measurements, the dimmings merely suggest planets; their presence is confirmed by ground-based telescopes that look for the "wobble" - a method known as radial velocity measurements.

In the case of Kepler-11, the planets orbit their host star so close to one another that they have noticeable gravitational effects on each other. These effects rhythmically change the time that each needs to orbit the star, and the authors were able to work out the masses of the planets.

'Totally unexpected'

As the report - published also on the Arxiv server, external - describes, all of the planets orbit their host star closely - five of them closer to their star than Mercury is to our Sun, and the sixth just beyond that distance. Two orbit at a distance just one-tenth as far as the Earth is from the Sun.

What is surprising is that all the planets are comparatively large; the system has a total of 10 times the mass of the Earth inside the radius of Mercury's orbit; here in our Solar System, there are only about two Earth masses contained in a radius five times that of the Earth's orbit.

"Large planets very close in orbit around a single star were just totally unexpected," said lead author of the study Jack Lissauer of Nasa's Ames Research Center.

"We think this is the biggest thing in exoplanets since the discovery of 51 Pegasi - the first exoplanet - in 1995."

Moreover, the fact that six planets could be spotted around the Kepler-11 star means that all of the planets must lie in an almost completely flat plane, flatter even than our own Solar System, and aligned edge-on to the Earth - otherwise Kepler would not have been able to spot all six passing in front of the star.

Dr Lissauer explained that the find challenges the notion that planets form by coalescing from discs of debris around young stars, bumping into each other violently in the later stages, casting them into irregular elliptical and out-of-plane orbits.

"I come from a planet formation theory perspective, and this has sent me back to the drawing board," he said.

More to come

Study co-author Jonathan Fortney of the University of California Santa Cruz said that rather than upending current theory, the Kepler-11 system will be a boon to astrophysicists exploring a fuller range of planet formation scenarios.

"Planetary science is very comparative - planets are so different from one another, you need them to be in similar environments and then compare them to each other," Dr Fortney said.

"In the Kepler-11 system, we have a fantastic laboratory - better than any planetary system yet found - to look at the planets and compare them to one another to understand how they've evolved over time."

David Latham of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics told BBC News that the Kepler-11 system was just the leading edge of a wave of results from Kepler, which will regularly be releasing the data it gathers by staring fixedly at over 150,000 stars.

With the new crop of candidate planets, and recent suggestions that candidates are likely to be confirmed eventually as planets, external, the catalogue of known exoplanets looks set to explode.

"This tells us about the architecture of planetary systems and gives us a context for trying to understand our own Solar System," he said.

"The 'holy grail' is to find something enough like the Earth that you could live there, but in the meantime I'm very distracted by these multiple [exoplanet systems]."

- Published3 February 2011

- Published10 January 2011

- Published26 August 2010

- Published24 August 2010