'Music of the stars' now louder

- Published

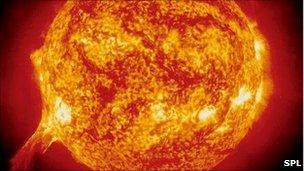

Kepler studies of distant stars will help us understand our own local star, the Sun, much better

The Kepler space telescope measures the sizes and ages of stars five times better than any other means - when it "listens" to the sounds they make.

Bill Chaplin, speaking at the AAAS conference in Washington, said that Kepler was an exquisite tool for what is called "astroseismology".

The technique measures minuscule variations in a star's brightness that occur as soundwaves bounce within it.

The Kepler team has now measured some 500 far-flung stars using the method.

Bill Chaplin of the University of Birmingham told the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science that astroseismology was, in essence, listening to the "music of the stars".

But it is not sound that Kepler measures. Its primary job is spotting exoplanets, by measuring the tiny dip in the amount of light that it sees when a planet passes in front of a distant star.

Such precision light-level measurements also work for astroseismology, because as sound waves resonate within a star, they slightly change both the brightness and the colour of light that is emitted.

Researchers can deduce the acoustic oscillations that gave rise to the ripples on the light that Kepler sees.

Like a musical instrument, the lower the pitch, the bigger the star. That means that the sounds are thousands of times lower than we can hear.

But there are also overtones - multiples of those low frequencies - just like instruments, and these give an indication of the depth at which the sound waves originate, and the amount of hydrogen or helium they are passing through.

Since stars fuse more and more hydrogen into helium as they grow older, these amounts give astroseismologists a five-fold increase in the precision of their age estimates for stars.

"With conventional astronomy, when we look at stars we're seeing the radiation emitted at their surfaces; we can't actually see what's happening inside."

"Using the resonances, we can literally build up a picture of what the inside of a star looks like - there's no other way of doing that. It's not easy to do, but we're now getting there, thanks to Kepler."

Kepler is not the first mission to lend itself to astroseimology; Canada's Most and Esa's Corot satellites, for example, are designed specifically to collect similar data.

But just the first few months of observations by Kepler has provided scientists with data on hundreds of stars, whereas Dr Chaplin said that only about 20 have been studied in detail before.

"Suddenly we have this huge database to mine," he said.

"I could literally spend the rest of my research career working on these data - we're just starting to mine them."