Bloodhound diary: Keeping a straight course

- Published

RAF fighter pilot Andy Green intends to get behind the wheel of a car that is capable of reaching 1,000mph (1,610km/h).

Powered by a rocket bolted to a Eurofighter-Typhoon jet engine, the Bloodhound car will mount an assault on the land speed record.

Wing Cmdr Green is writing a diary for the BBC News Website about his experiences working on the Bloodhound SSC (SuperSonic Car) project and the team's efforts to inspire national interest in science and engineering.

BUILDING THE 'WORLD'S FASTEST CAR'

I flew out to Daytona, Florida, to act as the "Grand Marshal" for the Rolex Daytona 24hr race.

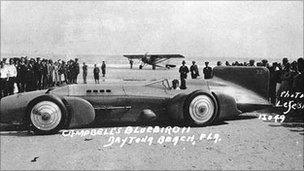

Malcolm Campbell had "a hell of a job" keeping his car straight at high speed at Daytona

The amazing thing was the Americans' response to Bloodhound. Everyone out there seemed to know about it and were dying to know more.

It even made the racing drivers stop and think when I explained that Bloodhound would be 10 miles away, from a standing start, in just 100 seconds, and that our third engine is a state-of-the-art 800hp Cosworth F1 engine, external "just" to drive the rocket pump.

I'm not sure they could get their heads around that one... and they're not alone.

Even in the land of the big and the bold, Bloodhound stands out as something extraordinary.

The chassis – half steel, half carbon, and all going into manufacture

There is, of course, a very special link between Daytona and the Land Speed Record. During the 1920s and 1930s, the 23-mile long beach at Daytona was the place to go to set a World Record.

Henry Segrave was the first man to exceed 200mph here and Malcolm Campbell touched 300mph for the first time on the same stretch of beach.

Campbell struggled to keep his car straight at 300mph on the sand. He gave up running on Daytona beach after this, in favour of the much harder Bonneville Salt Flats.

It will be interesting to see if Bloodhound has similar problems keeping straight on our dry lake bed in South Africa as we approach 1,000mph.

Knit your own chassis – 10 times a strong as steel

We've studied the problems of steering the car, external in great detail, but we won't really know until we get there.

The big news in January was the announcement of the chassis build, external. The chassis more-or-less divides into two halves. The front of the car is exposed to huge loads (up to 12 tonnes per sq metre of aerodynamic load at 1,000 mph) and is a very complex shape - so carbon fibre is the ideal material for the nose, cockpit and engine intake.

The rear half of the chassis is a much simpler shape, but is subject to the enormous heat and vibration of the EJ200 jet and Falcon rocket (133,000 thrust horsepower will shake your fillings loose in no time), so we're using a steel framework with metal panels for the rear end of the Car. The first drawings have been formally handed over to Hampson Industries, which is building the metal rear end, so it's really happening now.

90 tonnes of Airbus – could you hang one of these off your car? We can...

Last month, we also announced a contract with the Advanced Composites Group to build the front half of the car, which means that about 90% of the primary structure is now starting manufacture - fantastic!

Carbon fibre is amazing stuff. It's a "composite" material - fibres of carbon set in epoxy resin. For the same mass of material, it's about 10 times as strong as steel - and because the strength is determined by the direction of the carbon fibres, it can be built to take loads in a particular direction. It's like knitting your own structure, but it's a very complex process, which is why we need expert help.

To get some idea of how strong the chassis needs to be, consider this. The rear suspension pivots could see peak loads of up to 30 tonnes. For the whole chassis, the total load could be up to 90 tonnes - which is about the load that the mast of an America's Cup super-yacht has to take (and ACG makes them, so they should know). It's also the same weight as a fully loaded Airbus A321 with fuel, passengers and all the duty-free.

Richard Noble, Bloodhound project director, at Havering College

The more I think about this, the more pleased I am that we've got world-class companies like Hampson and ACG building a really strong chassis for us. This is one thing I don't want to be worrying about as we approach 1,000mph.

The key part of this project is inspiring the next generation of scientists and engineers and, to date, we've signed up 4,203 schools and colleges to the Bloodhound Education Programme, external. I got a reminder of just what that means with a visit to Derby College for National Apprentice Week, external. After five presentations in six hours I'd just about lost my voice - but still the questions kept coming, which was great.

The only problem right now, for all of us, is not having more time to get out to the schools - but we're doing as many as we can.

Hakskeen Pan – currently a lake 1 inch deep and 12 miles long

Things have been quiet out in South Africa over the past few weeks, as it's the middle of the rainy season and our track on Hakskeen Pan is too wet to work on.

All the rain will be gone in a couple of months' time and then the clearance work will resume. We have a huge group of UK volunteers who have offered to come and help, so we're hoping to take a group out there in the Spring (when the wet season has definitely finished).

I can't wait to get out there and see what the track looks like - 24 million sq metres of hand-cleared surface is going to be quite a sight: the world's best race track.

Wing Commander Andy Green: "This is an engineering adventure to take science to the limit"

- Published7 February 2011

- Published21 November 2010

- Published13 November 2010