Microscope with 50-nanometre resolution demonstrated

- Published

The technique can see features significantly smaller than prior efforts

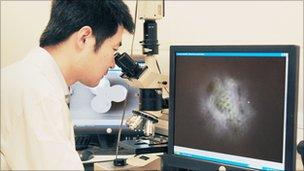

UK researchers have demonstrated the highest-resolution optical microscope ever - aided by tiny glass beads.

The microscope imaged objects down to just 50 billionths of a metre to yield a never-before-seen, direct glimpse into the "nanoscopic" world.

The team says the method could even be used to view individual viruses.

Their technique, reported in Nature Communications, external, makes use of "evanescent waves", emitted very near an object and usually lost altogether.

Instead, the beads gather the light and re-focus it, channelling it into a standard microscope.

This allowed researchers to see with their own eyes a level of detail that is normally restricted to indirect methods such as atomic force microscopy or scanning electron microscopy.

Some of these indirect methods have imaged to a resolution of one billionth of a metre (nanometre), and even given a glimpse of a single molecule - but none is the same as simply looking down a microscope directly at details this tiny.

Using the full spectrum of visible light - the kind that we can see - to look at objects of this size is, in a sense, breaking light's rules.

Normally, the smallest object that can be seen is set by a physical property known as the diffraction limit; for visible light, that limits resolution to about 200 nanometres.

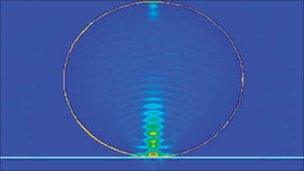

Light waves naturally and inevitably "spread out" in such a way as to limit the degree to which they can be focused - or, equivalently, the size of the object that can be imaged.

At the surfaces of objects, these evanescent waves are also produced.

As the name implies, evanescent waves fade quickly with distance. But crucially, they are not subject to the diffraction limit - so if they can be captured, they hold promise for far higher resolution than standard imaging methods can provide.

Going viral

"Previously, people including ourselves have been using microspheres for focusing light for fabrication purposes, so we can machine features smaller than the diffraction limit," explained Lin Li, of the University of Manchester's Laser Processing Research Centre.

"It just came to my mind that if we reverse it, we might be able to see small features as well, so that is the reason we carried out this piece of research," he told BBC News.

Professor Li and his colleagues used glass beads measuring between two and nine millionths of a metre across, placed on the surfaces of their samples.

The beads gather up and re-focus light that normally fades away within nanometres of the sample

The beads collect the light transmitted through the samples, gathering up the evanescent waves and focusing them in such a way that a standard microscope lens could pick them up.

The team quotes a resolution of 50 nanometres - a record for this kind of direct viewing with "white light" visible illumination.

The team imaged minuscule features in various solid samples and even the nanometre-scale grooves in Blu-Ray discs to show that the approach's resolution beat all previous records for optical microscopy.

But Professor Li thinks that, with further improvements to the approach, it could hold great promise for biological studies - for which the action at the nanoscale is difficult to see directly.

"The area we think will be of interest will be looking at cells, bacteria, and even viruses," he said.

"Using the current technology, it is very time consuming; for example, using fluorescence optical microscopy, it takes up to two days to prepare one sample and the success rate of that preparation is 10 to 20%. That illustrates the potential gain by introducing a direct method of observing cells."

Ortwin Hess of Imperial College London said that "it's really quite fascinating and exciting to see these effects coming together".

"If you use the fact that you do generate those (evanescent waves) and focus them again, then you have a tight focal point that you wouldn't normally expect to have," he told BBC News.

"It's quite a nice phenomenon that they've absolutely exploited."

What is a nanometre? Professor Tony Ryan explains

- Published18 February 2011

- Published5 September 2010