Difficult decisions ahead on Mars

- Published

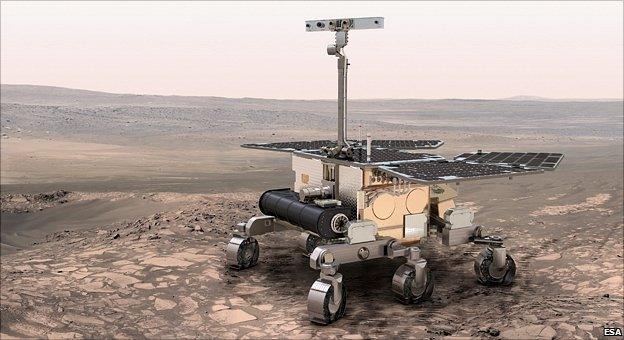

An artist's impression of ExoMars - Europe has completed its design and is now ready to build it

The joint Mars exploration envisioned by the US and Europe is set for an overhaul, following an announcement by the Americans that their part of the budget is critically short of funds.

Nasa and Esa had agreed to send two rovers to the Red Planet in 2018.

In Europe's case, this vehicle is already designed and about to be built.

But a new report from the US National Research Council, external says the probable $3.5bn (£2.2bn) cost of the American side of the mission is $1bn too high.

The "planetary decadal survey" - which is only an advisory document at this stage - recommends the effort be scaled back or postponed indefinitely.

As an example scenario of how the mission could be modified - or de-scoped - to fit within the new suggested budget, the report considers the situation in which the European rover is simply left behind on Earth.

Such a one-sided outcome from a revision process is not thought to be likely, but it gives a sense of the difficulties Nasa and Esa now face in developing a joint initiative to land and rove on Mars later this decade.

"We're quite confident that a really good mission can be done for $2.5bn," said the survey's chairman Professor Steve Squyres, "but we leave it to those two agencies to work out exactly the details of what that would look like.

"Critically, we feel that the de-scopes have to be shared equitably between Nasa and Esa because it's so important to preserve the partnership with Esa. We can't force all the bad news on to Esa; it's got to be a fair split."

Rocky path

Professor Squyres, from Cornell University, was presenting the findings of his working group's report - formally called Vision and Voyages for Planetary Science in the Decade 2013-2022 - at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (LPSC) in the Woodlands, Texas.

Although just an advisory document, it is deemed to represent the broad views of the US planetary science community and will therefore guide Nasa policy decisions.

The ultimate desire of both Nasa and Esa is to return rock samples from Mars for study in Earth laboratories.

The report from Steve Squyres and his committee will be extremely influential

As such, the report believes the 2018 opportunity should be the highest planetary priority for Nasa, the reasoning being that it would begin the sample-return quest.

While the European, or ExoMars, rover would drill below the planet's surface to search for signs of life, the American Max-C rover would seek out and package interesting rocks. Robots despatched to Mars deep in the 2020s would then pick up this cache, blast it off the surface into orbit before next routing it back to Earth.

Budgetary concerns had already prompted Nasa and Esa to merge their Mars exploration priorities.

The idea of putting ExoMars and Max-C on the same rocket and sharing the same landing system was a direct consequence of this joint thinking.

However, changing financial circumstances in the US mean the scope of this plan should now be re-thought, says the decadal report.

The recent budget request for Nasa made to the US Congress envisages declining funds for the agency in the next five to six years, meaning the "science per dollar" delivered by every mission had to be thoroughly scrutinised and justified, said Professor Squyres.

"If that goal of $2.5bn [for Nasa's contribution to 2018] cannot be achieved for whatever reason, our recommendation is that Max-C should be deferred to a subsequent decade or cancelled," he told the Woodlands meeting.

The two agencies are due to hold bi-lateral discussions later this month.

All about cooperation

They already have one near-term joint venture to the Red Planet that is signed off and being prepared: an orbiter that would go Mars in 2016 to seek out sources of methane and other trace gases in the atmosphere.

The results of this mission could conceivably guide the decision of where to land the 2018 effort.

Methane presence is intriguing because it could indicate either present-day life or geological activity, and confirmation of either would be a major discovery.

But precisely what happens now in 2018 will be the subject of a new discussion.

Dr Jim Green, the director of Nasa's planetary science division, told the LPSC meeting: "In terms of our flagship missions - the ones we have planned with Esa - it is clear we must go back to the negotiating table and re-work new agreements if we expect to maintain our partnership with our best foreign partner to date."

But the motivations behind the announcement were made clear as he added: "As everyone knows, we are in completely different economic times and we must take that into account."

The decadal survey's second and third flagship priorities are two orbiters - one to go to the Jovian moon Europa and the other to go to Uranus.

Again, the report says that unless these missions can be substantially reduced in cost, Nasa should defer them and pursue more of the cheaper, smaller-scale missions instead.

Reacting to the release of the report, the director of science at the European Space Agency, Professor David Southwood, said the decadal needed careful consideration before judgement was passed.

"We need to get a clear picture of what the Americans really want to do," he told BBC News. "We also need to be clear to what extent, if we run up a flag and decide to do something, the Americans will want to join us. It's all about cooperation.

"We will meet them at the end of March and will hope to come out of that discussion with some decisions about where we are going. The decadal raises a lot of questions and we have to answer them."