Save energy for economy, EU Commission urges

- Published

The commission makes the economic case for acceleration, but the politics are a little more opaque

EU nations must invest more in energy efficiency and green technologies in order to retain economic advantages, the European Commission has urged.

The exhortation comes in the commission road-map to 2050, external on climate and energy.

Its key message is that the bloc risks losing out to competitors that are putting more money into these areas - especially if oil and gas prices rise.

However, as we reported on Friday, the commission is not explicitly urging new targets for cutting EU emissions.

''We need to start the transition towards a competitive low carbon economy now," said EU Climate Commissioner Connie Hedegaard.

"The longer we wait, the higher the cost will be.

"As oil prices keep rising, Europe is paying more every year for its energy bill and becoming more vulnerable to price shocks. So starting the transition now will pay off."

The price of oil has approximately doubled since 2005, with the road-map describing further hikes as likely.

"Taken over the whole 40-year period, it is estimated that energy efficiency and the switch to domestically produced low carbon energy sources will reduce the EU's average fuel costs by between 175-320bn euros ($244-448bn) per year," it says.

The transition will also generate jobs, it concludes.

The number of people working in the renewables industry has more than doubled over the last five years. The commission projects that serious investment could increase the total number employed in this sector to 1.5 million by 2020.

Triple target

Back in 2008, the bloc set three parallel targets for 2020:

cutting emissions by 20% from 1990 levels

delivering at least 20% of its energy from renewable sources

increasing energy efficiency by 20%

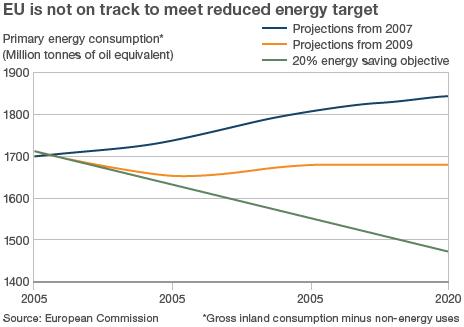

The bloc is on course to achieve the first two, but not yet the third. In parallel with the road-map, the commission is also publishing proposals on how EU nations can push faster towards the efficiency target.

Among its components are a requirement to refurbish at least 3% of publicly-owned building stock each year, establishment of efficiency standards for public building stock, and the roll-out of smart meters.

Climate Commissioner Connie Hedegaard is spear-heading attempts to set tougher EU targets

Energy Commissioner Gunther Oettinger said this "paves the way for the longer term policies needed to achieve a decarbonised and resource-efficient economy by 2050 and to place the EU at the forefront of innovation".

Calculations done for the road-map show that if the efficiency target is achieved on top of the renewables goal, emissions will fall 25% from 1990 levels by 2020 without the need for any extra measures - which is one of the reasons why climate campaigners have been urging the bloc to set a tougher target than 20% by 2020.

The other strand to their argument is that the recession caused such a large fall in emissions that from hereon in, achieving 20% by 2020 involves cutting emissions slower than the EU has done historically.

The EU's long-term goal is to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 80-95% by 2050, with 80% achieved through measures at home and any additional amount through international mechanisms such as the UN's Clean Development Mechanism.

Analysis conducted for the road-map concludes that the most cost-effective pathway to that long-term goal would take the bloc through an intermediate target of a 25% emissions cut from 1990 levels by 2025, achieved through domestic measures only.

But it also says: "This Communication does not suggest to set new 2020 targets, nor does it affect the EU's offer in the international negotiations to take on a 30% reduction target for 2020, if the conditions are right".

The decision not explicitly to urge the 25% target that is endorsed by the commission's own analysis is perhaps a sign of the in-fighting that has taken place between the departments of Ms Hedegaard and Mr Oettinger.

While Ms Hedegaard and her allies have argued for tougher emission caps, Mr Oettinger's camp contends this would lead to the "de-industrialisation" of Europe.

Member states have taken different positions, and in some countries there are splits between ministries.

Business too is split, with some companies agreeing with Mr Oettinger and others backing the line taken in the road-map, that delaying investment now will jeopardise competitiveness.

"Over the last few weeks, lobbyists for Europe's dirtiest corporations have frantically sought to strip the European climate plan of any ambition whatsoever - but they have failed," said Ruth Davis, chief policy adviser at Greenpeace.

"The case for Europe making a 30% cut is now just unarguable, and should happen without a reliance upon offsets from abroad."

UK Energy and Climate Secretary Chris Huhne agreed, saying: "The road-map shows that Europe's current 20% target for 2020 isn't enough or cost-effective, and shows that Europe's already got the policies and the tools to cut emissions by 25% at home.

"This makes the case for going to 30% stronger and more urgent."

Making allowances

One block to achieving the level of investment recommended by the road-map is the low price of carbon - driven largely by the fact that the recession meant companies achieved emission cuts without having to pay for them. So there is a surplus of allowances to emit.

The commission concludes that "appropriate measures" for keeping the price high "need to be considered, including recalibrating the EU Emission Trading Scheme by setting aside a corresponding number of allowances from the part to be auctioned during the period 2013 to 2020 should a corresponding political decision be taken".

The road-map will be debated by member states through the European Council, and by the European Parliament.

What emerges at the end of that process will become EU law.

- Published4 March 2011

- Published29 April 2010

- Published3 June 2010