Japan tsunami 'could be 1,000-year event'

- Published

The death toll is not known, but could run into the tens of thousands

Tsunamis on the scale that hit north-east Japan last week may strike the region about once every 1,000 years, a leading seismologist has said.

Dr Roger Musson said there were similarities between the last week's event and another giant wave that hit the Sendai coast in 869AD.

It is not unusual for undersea earthquakes to generate tsunamis in this part of Japan. Offshore quakes in the 19th and 20th centuries also caused large walls of water to hit this area of coastline.

But previous research by a Japanese team shows that in the 869 "Jogan" disaster, tsunami waters moved some 4km inland, causing widespread flooding.

The researchers said that such gigantic tsunamis occur in the area roughly once every 1,000 years. Dr Musson, who is the head of seismic hazard at the British Geological Survey (BGS), suggested the latest tsunami was comparable to the event in 869.

Quake rule

The most recent tsunami waves were up to 10m high; it is unclear how far inland the waters travelled, but reports say it was on the order of several miles.

Dr Musson told BBC News: "I would imagine it would be about the same, because it is hard to think that there would be any larger earthquakes than this in this part of the world."

The tsunami has devastated coastal areas of north-east Japan

The BGS seismologist acknowledged there had been other notably large earthquakes in the region in 1933 and in the 1890s. But he said: "There is a convenient little fact to remember... if you know how often Magnitude 9 earthquakes are, you will get Magnitude 8 earthquakes roughly 10 times as often and Magnitude 7 earthquakes approximately 100 times as often."

However, another researcher contacted by BBC News said they would be cautious to draw conclusions about the frequency of such events, given how seismically active this region is.

Far inland

About 10 years ago, a team led by Professor Koji Minoura, from Japan's Tohoku University, analysed sediments from the Sendai and Soma coastal plains that preserved traces of the tsunami in 869.

Their results, published in the Journal of Natural Disaster Science, indicated that the medieval tsunami was probably triggered by a Magnitude 8.3 offshore quake and that waters spread more than 4km from the shore.

They also found evidence of two earlier tsunamis on the scale of the Jogan disaster, leading them to conclude that there had been three massive events in the last 3,000 years.

Dr Lisa McNeill, a geophysicist at the National Oceanography Centre, Southampton, told BBC News: "There are several ways you can find out about past events, before we began to record earthquakes on seismometers in the 1900s - one is through historical records, the other way is through geological records.

"You can either look for evidence of tsunamis, or you can look for evidence that the ground has moved rapidly up or down due to the earthquake itself. That is what happens to the seafloor and generates the tsunamis. In some cases, underwater sediment flows can be triggered by the earthquakes and these may leave a datable record which we can identify in sediment cores."

Dr McNeill said it can be difficult to estimate a precise magnitude from limited geological data and historical records. But she said that - broadly speaking - there was a good correlation between the size of an earthquake and the size of a tsunami.

Planning ahead

She explained: "That usually works reasonably well, but there are some deviations. Some of them are due to local effects at the coastline: either the shape of the coastline - which can focus and increase the amplitude of tsunami waves - and the local bathymetry (seafloor relief).

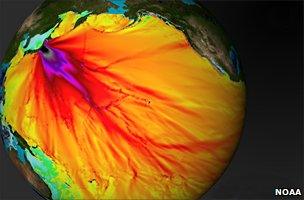

US scientists estimated the progression of the tsunami over the entire Pacific basin

"There can sometimes be additional effects that deform the seafloor such as undersea landslides or other faults that moved at the same time, which affect how the seafloor deforms."

Professor Hermann Fritz, a tsunami expert from Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech), US, said: "Nowhere in the world is as prepared as Japan - but in general you can plan for a magnitude 7 or 7.5 that happens every generation, but not for anything in the 9 range.

"The relationship [between earthquake size and tsunami size] is not linear, and it depends on how the rupture actually occurs. If the rupture is actually on the seafloor you get a much bigger displacement - then again if you get something like 7.2 somewhere deep in the Earth, that won't create a tsunami at all.

"Once it's a full megathrust rupture, Magnitude 9, then basically the entire zone ruptures from deep down up to the surface.

He added: "Each event is going to be different, and it can also be dangerous to plan on past events only - even in Japan where the record is long, it might still not be long enough."