Reactor breach worsens prospects

- Published

A third explosion at the site appears to have damaged reactor 2's containment

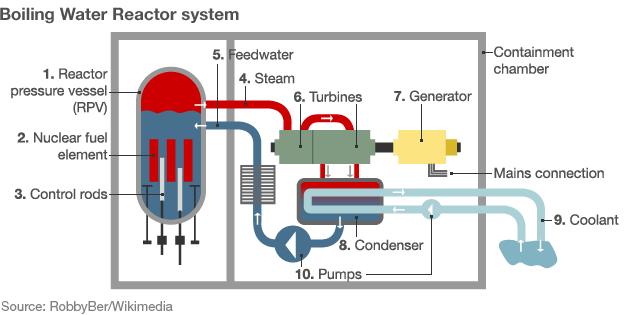

It appears that for the first time, the containment system around one of the Fukushima Daiichi reactors has been breached.

Officials have referred to a possible crack in the suppression chamber of reactor 2 - a large doughnut-shaped structure, also known as the torus, below the reactor housing.

That would allow steam, containing radioactive substances, to escape continuously.

This is the most likely source of the high radioactivity readings seen near the site in the middle of Tuesday.

Under normal circumstances, the suppression chamber stores a large volume of water that can be used to condense steam produced in the reactor.

The industry newsletter World Nuclear News reports that a "loud noise" came from the reactor chamber, and that "the pressure... was seen to decrease from three atmospheres to one atmosphere after the noise, suggesting possible damage".

This pressure drop is consistent with the chamber cracking and releasing steam.

Once de-pressurised, material would probably be ejected at a slower rate. This is consistent with the swift fall in readings taken around the plant later in the day.

Another possible source was a fire and explosion in the building housing reactor 4.

At the time of the earthquake, reactors 4, 5 and 6 were shut down for planned maintenance.

During this period, fuel rods are withdrawn from the reactor and stored in a pool - looking like a big swimming pool - in the upper level of the reactor building, outside the containment vessel.

The water keeps them cool, and protects workers below from radiation.

The rods may later be placed back in the reactor or taken away for long-term storage and re-processing, depending how long they have already been in service.

An official with the Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco), which owns the station, told BBC News that the cause was believed to be a lack of water in the pool.

This caused the rods to overheat, reacting with steam and generating hydrogen - which then ignited, similar to the earlier blasts in reactor buildings 1, 2 and 3 when hydrogen was vented from the reactor vessel.

But at a news briefing in London, academics were perplexed by the idea.

"The fuel pins in the pond should be totally contained, there should be no damage," said Laurence Williams, professor of nuclear safety at the University of Central Lancashire.

"If you did have a fire, you'd have the same issues (as in a reactor melt) - you'd have fission gases in the spaces inside the fuel pin, depending on how long the fuel was in there the iodine might or might not be a hazard... overall, I'm quite mystified."

Kyodo News, the main Japanese news agency, reported that technicians were unable to pump water back into the pool and that helicopters may be used to dump water into the building from the air.

However, according to the US-based Nuclear Energy Institute (NEI), the Japanese Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) was working on a different theory - ascribing the fire to an oil leak.

Improvised solutions

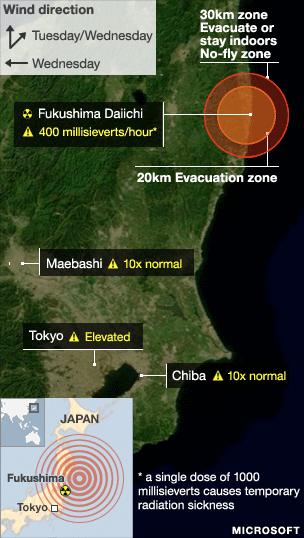

The government is clearly concerned about the possible health impact of radioactive material escaping from Fukushima, with Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano recommending: "Please do not go outside. Please stay indoors. Please close windows and make your homes airtight."

Whatever the precise source of the radioactivity, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) reported: "Dose rates of up to 400 millisievert per hour (mSv/hr) have been reported at the site."

Acccording to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the average person's exposure is 3mSv in a year.

Without knowing the full scope of the release, it is hard to assess the likely impact on health.

There is as yet no comprehensive picture of readings across the wider region - and wind direction is a major factor. Nor is it clear for how long the elevated levels persisted.

The US National Institutes of Health notes that a dose approaching one sievert (1,000mSv) would certainly induce radiation sickness.

But in the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, some workers who received doses above this level are still alive.

Whether there is a straightforward relationship between exposure and cancer risk remains unclear, with some experts believing low levels do not have an impact.

It also depends which substances are involved. A major risk is when the body absorbs and stores substances such as radioactive iodine, which leads to prolonged, internal exposure.

Experts at the London briefing were keen to put the maximum risk in context.

"Even if the worst does happen, if we do have a significant containment breach, we're absolutely not looking at another Chernobyl," said Professor Malcolm Sperrin, director of medical physics and clinical engineering at Royal Berkshire Hospital.

"We're looking at volumes that will be distributed in the air,and the dose downwind is going to be very low - and the wind now is over the sea."

And Richard Wakeford, visiting professor in epidemiology at the University of Manchester, said Japanese authorities had acted quickly and wisely - unlike Soviet authorities at the time of the Chernobyl disaster.

"They evacuated people early in case there were a release, because the principal concern would be the radioactive iodine," he said.

"The Soviet authorities were in denial - they didn;t move people out, they didn't stop children drinking milk - and even then, the only indication of this is an excess in thyroid cancers, which would not have happened if authorities had issued iodine tablets and stopped people eating the food."

Improvising solo

In the meantime, the key task for workers at the plant remains to get enough water into the reactors - and, now, into the spent fuel pools - with the poor resources at their disposal.

Among all the news coming out of Fukushima from the Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco), the nuclear safety agency, and local and national authorities, there has hardly been a mention of new equipment arriving at the site.

That implies that technicians are still working with water pumps designed for putting out fires and an improvised technique based on the turbine hall's fire extinguishing system.

The Tepco official confirmed that most of the station's staff have been evacuated, with only about 50 remaining on site.

If the suppression chamber in number 2 building has cracked, the positive side is that it could make the job of cooling the reactor easier.

At times, technicians have struggled to force water into the reactor vessel simply because the pressure inside was too great. The downside is that the water will turn to steam more easily at a lower pressure.