Fukushima - disaster or distraction?

- Published

The government's swift imposition of a protection zone may have kept any health impact down

As it was almost bound to do at some point, Japan's nuclear safety agency has uprated its assessment of the Fukushima power station incident from a level four to a level five.

These are categories on the International Nuclear and Radiological Events Scale (INES), which runs from zero (nothing happened, essentially) to seven, a "major accident".

So far, Chernobyl is the only seven-rated incident in nuclear history.

Level five is defined as an "accident with wider consequences".

So what is the worst-case scenario for those "wider consequences" at Fukushima?

What clues are there either from that level five rating, or from the situation on the ground, as to how things might transpire - whether it will in the end prove to have been a disaster or a distraction from the serious and widespread impact of the tsunami?

"The worst-case scenario would be where you have the fission products in stored canisters or in the reactors being released," said Professor Malcolm Sperrin, director of medical physics and clinical engineering at Royal Berkshire Hospital, UK.

"Radiation levels would then be very high around the plant, which is not to say they'd reach the general public.

"And we're definitely not in the situation where we're going to see another Chernobyl - that possibility has long gone."

Distant advice

The level five rating applies specifically to the nuclear reactors in buildings 2 and 3 at Fukushima, rather than to the spent fuel cooling ponds that have lost water and where the stored fuel is heating up.

That implies that the regulators believe the main source of radioactivity coming from the plant has been the reactors.

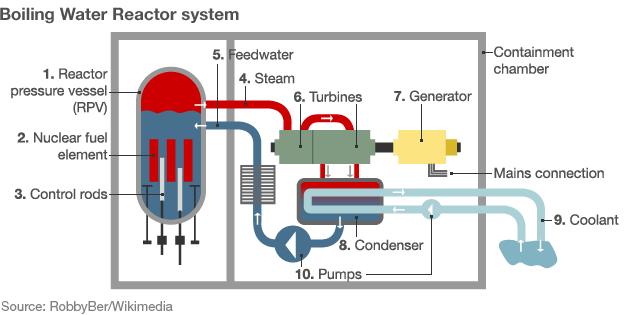

Certainly, one of the the spikes in readings earlier in the week appeared to co-incide with damage to reactor number 2, believed to be a crack in the containment system - the symptoms being a sharp release of steam and an abrupt drop in pressure.

On Thursday and Friday, radiation levels around the plant appeared much more stable.

And although elevated readings have been noted in some locations 30km from Fukushima, there has been nothing outside the 30km protection zone that has appeared to pose a danger to health.

Despite this, a number of governments have advised their citizens to stay much further away - or in the case of the UK, to consider doing so.

However, when the UK's chief scientific adviser explained the reasoning to BBC News on Thursday, he was still painting a worst-case scenario that appeared some way short of apocalyptic.

"The worst-case scenario would see the ponds starting to emit serious amounts of radiation, with some of the reactors going into a meltdown phase," he said.

"We put that together with [a possible scenario of] extremely unfavourable weather conditions - wind in the direction of Tokyo, for example.

"Even in that situation, the radiation that we believe could come into the Tokyo area is such that you could mitigate it with relatively straightforward measures, for example staying indoors and keeping the windows closed."

Local issue

Fukushima now becomes the third level five incident in half a century of nuclear technology.

The Windscale fire could have been far worse if filters had not been installed at the tops of the chimneys

The first was the Windscale reactor fire in the UK in 1957 - the second, the partial meltdown of a reactor at Three Mile Island in the US in 1979.

Richard Wakeford from the Dalton Nuclear Institute, a visiting professor in epidemiology at the University of Manchester, recently re-assessed the effect of radiation released at Windscale.

Using data and computer models, his scientific paper concluded that the release could have caused about 240 cases of cancer, half of them fatal.

However, inquiries into Three Mile Island concluded it probably caused no deaths.

That raises the question of why both are in the same INES category, given that Three Mile Island did not, in the end, have more than a local impact.

"The reason why Three Mile Island was rated a five is that there was major damage to the reactor core and there was potential for a widespread release of radioactive material - it didn't happen, but that potential is built into the event scale," said Professor Wakeford.

In terms of material released, he said: "Fukushima is somewhere between the two - clearly there have been releases, and you have a possible breach of the containment system - no-one really knows."

Slow down

As time passes, the reactors should in principle become less dangerous.

The rate at which they pump out heat decreases quickly, and by now the rate should be down to about one-thousandth of what it was a week ago, just before the Tohoku earthquake triggered a shutdown.

Prospects of exposure to perhaps the most dangerous radioactive substance, iodine-131, also diminish rapidly.

It decays quickly through radioactivity - after eight days, half the atoms present initially will already have decayed away.

There should be very little left in fuel rods that have been in storage ponds since November.

In addition, the continuing efforts to keep seawater flowing into reactors 1, 2 and 3 appear to have been relatively successful on Thursday and Friday.

If the reactors have been cooled, fuel rods will have been degrading at a slower rate, again curbing the release of radioactive substances.

On Friday afternoon, radioactivity readings had reportedly declined to less than 500 microsieverts per hour on site - below the level at which operators have to sound the alarm.

Some governments have advised their nationals to keep well away

Nevertheless, computer simulations by the French Institute for Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety (IRSN) indicate that harmful levels of radioactivity could have been experienced close to Fukushima but outside the 30km protection zone - though not further afield.

Greenpeace, with a long history of opposition to nuclear power, is not convinced that the time has come to declare that the risk of a major accident has subsided.

The group's nuclear campaigner Jan Beranek outlined a scenario where radioactive material was dispersed through fires or gas explosions of the type we saw earlier in the week.

"The mechanism could be destruction of the cladding around the fuel rods and fire - leading not only to the relase of radioactive iodine and caesium, but also opening fuel rods to the air," he told BBC News.

"With the fuel ponds, there is no barrier to further release.

"With the reactors, you could have a steam or hydrogen explosion if they try to pour water too quickly, and another explosion could give the final blow to the containment."

Hooking up

The cure for the plant's immediate problems could be the restoration of electrical power.

A grid connection was hooked up on Friday, although technicians were clearly struggling to power up systems around the site given that some of the plant's internal circuitry had been damaged by the tsunami or the gas explosions.

The nuclear safety authority outlined a timescale that would see power restored in reactor buildings 1-4 by Sunday.

If this all works, the prospects of the Greenpeace scenario should recede.

Then it will be time to take stock. And it may turn out, said Richard Wakeford, that no deaths at all will be attributable to the Fukushima incident.

"If you take one of the workers who's been exposed to 100 milliSieverts (mSv), that's not going to have any serious short-term effects," he said - "certainly nothing like the situation facing the Chernobyl emergency workers that killed 28 of them.

"The risk of a serious cancer arising from that kind of dose would be less than 1% in a lifetime - and you have to consider that the normal chance of dying from cancer is 20-25% anyway.

"As for people outside the plant - I can't see any chance of picking out the effect of the Fukushima releases against the general background of cancers."