Prehistoric reptile skin secrets revealed in new image

- Published

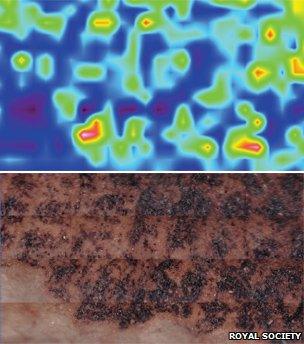

The infra-red mapping (top) has allowed the team to suggest how the sample was preserved

A unique image, for the first time, has mapped organic compounds that are still surviving in a 50-million-year-old sample of reptile skin.

The infra-red picture reveals the chemical profile of the skin, offering an insight into how it was preserved.

A team of UK scientists say the sample was so well preserved that it was hard to tell the difference between the fossil and the fresh samples.

The details appear in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, external.

"It is a relatively new technique - I think we are the first people to apply it to palaeontology," said co-author Roy Wogelius, a geochemist from the University of Manchester, UK.

He told BBC News that the technology allows non-destructive analysis, meaning that it could be used on rare, valuable museum specimens.

"Now we can apply this organic technique [it] means that there is an awful lot of material that we can analyse in ways people did not realise were possible."

Possible specimens could include invertebrates, marine creatures and plant material, Dr Wogelius said.

The 50-million-year-old fossil allowed the team to profile prehistoric biochemicals

He explained that the the infra-red mapping technique worked in a manner that was similar to a record player.

"What you do is you take something that transmits light, so if you take a very small needle - about the size of an old phonograph stylus - and make it so it can transmit light," he revealed.

"You can shine light down through the needle and then when the needle is in contact with the specimen's surface, a little of that light will be absorbed - that is the signal that we use.

"When there is a little more absorption at a certain frequency, that is a fingerprint for a particular organic compound."

Dr Wogelius explained that the team of UK and US researchers had attempted to use the technology before, on a sample from a sample known as "dino-mummy", a 67-million-year-old fossil that still had much of its soft tissue intact.

"This was one of the best preserved dinosaurs discovered, and we were able to show that there was organic compound from the skin remaining (on the fossil)," he observed.

"The problem was that the (sample) fell apart so easily, we could not map anything. So while we were confident that what we had was skin residue, we just could not see if there was any biological structure there."

Prehistoric 'whiff'

With the latest sample, Dr Wogelius said that the preservation was both remarkable and, perhaps more importantly, solid.

"It was also flat which made it very, very convenient to map it," he added.

"So we took this new technology... and the detail of what we were able to reveal was quite striking."

Using the infra-red technique, as well as a series of X-rays, the team were able to confirm that soft tissue was present on the fossil.

They were also able to offer a hypothesis on how the tissue had survived for 50 million years.

The details from the study suggest that when skin's organic compounds began to break down, they formed a chemical bond with trace metals that, under certain circumstances, then go on to build a "bridge" with the surrounding minerals.

A result of this process meant that the skin and remaining soft tissue was protected from further decomposition or further erosion.

"These new infra-red and X-ray methods reveal intricate chemical patterns that have been overlooked by traditional methods for decades," Dr Wogelius explained.

"We have learned that some of these compounds, if the chemistry is just right, can give us a bit of a whiff of the chemistry of these ancient organisms."

He went on to say that the team's findings had offered an insight into a number of area.

"By doing the infra-red analysis, we get some detail about the soft tissue that remains," he said.

"In fact, the chemical remains - in terms of the organic compounds - very closely resemble what we get when we look at modern gecko skin. That means that some of the organic components have been conserved over that period of time.

"Some of the trace metal chemistry is also original to the organism, and that give us hope in terms of understanding some bio-metallic complexes, in particular understanding the colouration and pigmentation of the skin.

"It is very exciting because we can start to pull out more detail."

Dr Wogelius said that this sort of information could unlock a better understanding of a range of research avenues, including prehistoric creatures' diets.