X-ray technique peers beneath archaeology's surface

- Published

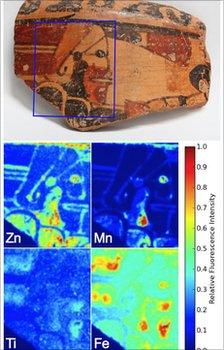

The technique can map the presence of each type of atom (zinc, manganese, titanium, iron)

Striking discoveries in archaeology are being made possible by strong beams of X-rays, say researchers.

A report at the American Physical Society meeting in Dallas, US, showed how X-ray sources known as synchrotrons can unravel an artefact's mysteries.

Light given off after an X-ray blast yields a neat list of the atoms within.

The technique can illuminate layers of pigment beneath the surfaces of artefacts, or even show the traces of tools used thousands of years ago.

This X-ray fluorescence or XRF works by measuring the after-effects of X-ray illumination.

As atoms absorb the X-rays, the rays' energy is redistributed, and very rarely some is re-emitted as light.

Each atom releases a characteristic colour of light, yielding a full chemical analysis, and as such the XRF technique is gaining ground as a means to meticulously analyse artefacts from the past.

Intense sources

Small X-ray sources have been used in the past to get a laundry list of atoms generally present in art, but Robert Thorne of Cornell University in the US told BBC News that the intense, focused X-rays from enormous sources known as synchrotrons have more recently shown their potential.

"These give you extremely intense X-ray beams, and what that allows you to do is not just collect a spectrum from one point, but you can 'raster scan' your sample in front of the beam and collect the full chemical analysis at each point."

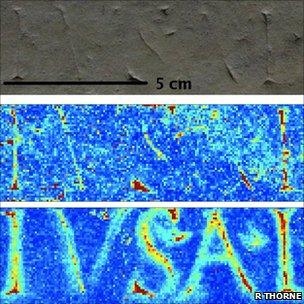

The technique has already been used to elucidate Roman and Greek inscriptions

Compared to handheld sources, he said, "you can get months' worth of photons delivered in a second, and that's critical".

Professor Thorne and his collaborators were in 2005 the first to use the technique to analyse inscriptions, external from Greek and Roman pottery.

The technique has been shown to shed light on layers of glaze beneath the surface of finished pottery.

It has even shown, in the case of an inscription that had worn entirely away, that minuscule amount of iron left by the chisel showed a pristine version of the inscription on what appeared to be smooth stone.

"We did an experiment at Diamond [Light Source in Oxford] last year on a heavily-worn surface, and we couldn't quite guess what the letters were," he said.

The translation said it was a decree involving three different individuals. We looked at the pattern of iron we saw from tool wear and pigments that one letter couldn't be consistent with the letter that had been put there - it turns out that letter changed the name of one of the people, and the story was about three brothers - just down to that one simple change."

More recently, the team - including Cornell physicist Ethan Geil and archaeologists Kathryn Hudson and John Henderson - has turned its attention toward the Americas. The technique is best used on artefacts whose inscriptions or decoration has worn away completely - but these, Professor Thorne said, are much harder to find because collectors and museums have until now viewed them as less valuable.

"That's what's exciting about working on pottery from Mesoamerica, because there's a ton of it in American collections, much of which we can get access to," he said.

"We're looking at some Mayan artefacts with some collaborators at Cornell and they're interested in the iconography of a particular subgroup within the Mayans.

"On the pottery a lot of the glaze has flaked off, so what you see is little black dots on the surface; it's very hard to tell if those black dots are glaze or dirt, but with the XRF you can tell."

Dr Thorne was guarded about the most recent results from the Mayan studies, which will be published soon.

"The message here is that physicists have developed this really fantastic technique to do full XRF imaging of objects.

"It's not a magic bullet - there never is in this business. But I think as a general tool for art and art historical and archaeological exploration, it's the best new thing to come out in a very long time."

- Published22 March 2011

- Published22 March 2011