Long game at Japan nuclear plant

- Published

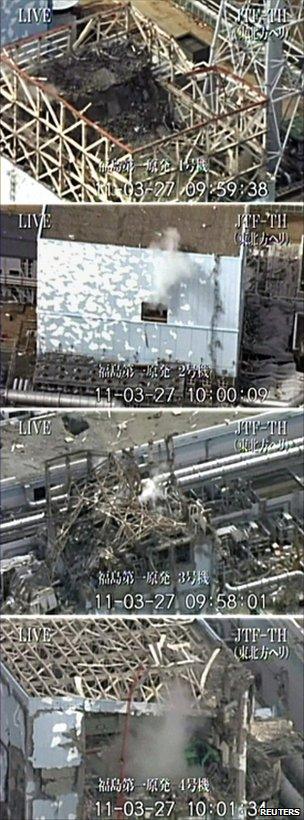

From top to bottom - Reactor Nos 1, 2, 3 and 4 at Tepco's Daiichi plant

We are now in a long game at the stricken Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan.

Two-and-a-half weeks on from the colossal Tohoku quake and its associated tsunami, engineers are working tirelessly to regain full control of the facility.

The past week has seen major gains in getting on top of the crisis, but difficulties and frustrations continue to hamper progress.

The major concern right now would appear to be the second reactor unit at the six-unit plant.

High levels of radiation have been found in waters in the basement of the building.

Doses at 1,000 millisieverts per hour have been measured - the highest readings recorded in the crisis so far.

Just 15 minutes exposure to this water would result in emergency workers at Daiichi reaching their permitted annual limit of 250 millisieverts.

Radioactive-contaminated water has also almost completely filled a tunnel system leading from the Unit 2 building.

Efforts are ongoing to ensure none of it floods out and into the ocean some 50m away.

Why the water is so contaminated is not completely clear, but the suspicion is that it has at some stage come into contact with nuclear fuel fragments from inside the reactor or from fuel rods stored in a cooling pond just outside it.

It may be the reactor's pressure and containment vessels or the pipework that feeds them has been compromised in some way. There is no definitive information on this.

"Together with the fact that the water found outside is highly radioactive, I think it can be said that this is proof that the fuel rod has melted a bit and this is a very serious thing," said Japan's Chief Cabinet Secretary, Yukio Edano. "We are doing our best to make sure we can stop (the further spreading of radioactivity) and contain the situation."

It is now a balancing act, Yukio Edano added. Water must be pumped continuously into the Number Two reactor to keep it cool, while at the same time not putting too much pressure on the system in case leakages of further radioactive water result.

"If the infrastructure doesn't deteriorate at Fukushima, the reactors are kept cold and the radiation is kept localised - then the level of radioactivity has to fall away naturally because the reactors are switched off," observed Paddy Regan, a British professor of nuclear physics at the University of Surrey.

"They seem to me to be doing exactly the right thing. Their protocol is to do whatever has to be done to keep the fuel rods cool. If they're not cooled there's still residual heat in them, called decay heat, and if the coolant evaporates and they're exposed to air then a combination of the heat and the fact they're exposed to air means you can have reactions on the zirconium cladding on the rods, and that is what releases the fission fragments."

The BBC's David Shukman looks at the dangers facing nuclear workers

Reactor Units One and Three also have water collected in their basements. Much of this water is likely the result of the spraying and "water-bombing" that occurred in the early days of the crisis to try to keep their reactors and storage ponds cool.

All of this water has to be removed so that engineers can repair equipment and get systems fully up and running.

Extracting it, however, has been hampered because some of the tanks into which it would be fed are themselves full.

Eventually the water will be cleaned. "The water can be put through an ion exchange system to take out radionuclides like caesium. That is relatively easily done; the technology is available to do that," explained Laurence Williams, another British professor of nuclear safety, at the John Tyndall Institute. "The caesium is removed and put in a shielded container and sent to a repository."

One other intriguing announcement this week has been the discovery by the plant's operators, the Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco), of traces of plutonium in soil samples close to the facility.

Three of five samples were said to be very typical of the traces one might expect to find in Japan as a result of the fallout from atmospheric atomic weapons testing conducted decades ago. But two samples were said to stand out because of the nature of the type, or isotopes, of plutonium atoms present. These, Tepco conceded, were what one might expect from nuclear reactions inside the plant. It could not say how the isotopes got there.

Japan's Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency explained that the detected levels of plutonium were not health-threatening for emergency workers at Daiichi, nor the residents in the surrounding areas. But the radionuclides' detection raises further questions about the integrity of the reactor systems at Daiichi and the damage they may have sustained.

In his most recent briefing, the head of the United Nations' nuclear watchdog, Yukiya Amano, described the situation at Fukushima as one that had "still not been overcome". In his view, he said it would "take some time to stabilise the reactors".

On the positive side, however, he noted that electrical power had now been restored to all three of the reactors that were operational at the time of the quake - Units One, Two and Three - and that fresh water was now available on the site to assist with cooling.

Reactor Four, which was not operating at the time of the quake but then caused concern because of a shortage of water in its storage pond, appears now to be under good control. Tepco was working to pump large amounts of freshwater into the pond.

The IAEA is going to convene a high-level conference in late June or early July to examine the repercussions of the Fukushima crisis.