Managing water is Fukushima priority

- Published

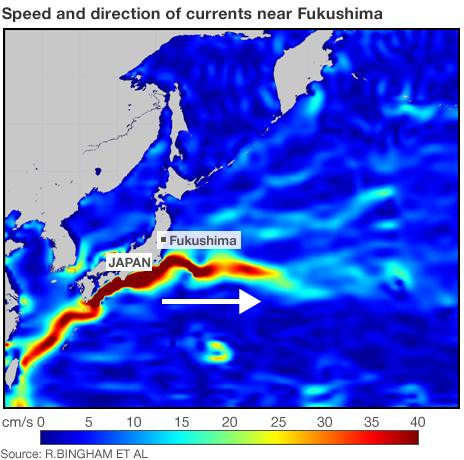

The Kuroshio Current may help to disperse pollutants

The company running the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant has begun releasing low-radioactive wastewater into the sea.

More than 10,000 tonnes will be pumped into the ocean in an operation the Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco) says will take several days.

It is now three-and-a-half weeks since the colossal Tohoku quake and its associated tsunami crippled the nuclear facility.

Engineers carrying out repairs continue to make steady progress but their efforts are being frustrated by large volumes of contaminated water.

Some of this water is mildly radioactive, some of it not; but all of the water has to be removed so that equipment damaged on 11 March and the explosions that followed can be properly fixed.

The key concern remains the second reactor unit at the six-unit plant.

High levels of radiation have been found in waters in the reactor building. This is water that at some stage has been in contact with nuclear fuel and has now pooled in the basement.

Doses at 1,000 millisieverts per hour have been measured. Just 15 minutes exposure to this water would result in emergency workers at Daiichi reaching their permitted annual limit of 250 millisieverts.

Workers have attempted to plug a crack in a trench thought to be involved in the ocean leak

This water itself is leaking into the ocean by an as yet unidentified route, and it has to be plugged.

Trace dye has been put in the water to try to see where it goes, but without success so far.

Efforts to try to fill a crack in a trench thought to be involved in the leak have also come to nought.

Tepco says the low-radioactive water it intends to deliberately release into the sea has iodine-131 levels that are about 100 times the legal limit.

But it stressed in a news conference on Monday that if people ate fish and seaweed caught near the plant every day for a year, their radiation exposure would still be just 0.6 millisieverts. Normal background radiation levels are on the order of 2 millisieverts per year.

Getting the mildly contaminated water off-site would permit the emergency staff to then start pumping out the turbine building and the much more radioactive liquid in its basement.

The Japanese government has approved the release. Chief Cabinet Secretary Yukio Edano said providing safe conditions to get into the Number 2 reactor to fix equipment was a higher priority.

And while no-one wants to see radioactive releases into the ocean, Japan is at least fortunate in the way the large-scale movement of the ocean works around the country.

It will take months to get on top of the crisis fully, say Japanese officials

The Kuroshio Current is the North Pacific equivalent of the Gulf Stream in the Atlantic. It hugs the Asian continental slope until about 35 degrees North, where it is deflected due east into the deep ocean as the Kuroshio Extension.

This means pollutants in its grasp will tend over time to be driven out into the middle of the Pacific where they will become well mixed and diluted.

The map on this page has just been released by the scientists working on the European Space Agency's Goce satellite.

The spacecraft measures gravity variations across the surface of the Earth and this information, allied to sea-surface height data, can then be used to work out current directions and speed.

"We've been able to resolve the Kuroshio Current now, using just space-based methods, better than we have ever been able to do before," explained Dr Rory Bingham from Newcastle University, UK.

"The Fukushima nuclear power plant lies within 200km of the core of the Kuroshio Extension," he told BBC News.

"There are many caveats here and I cannot say for certain how the extension will impact on any dispersal of radioactive pollutants, but certainly having a detailed knowledge of the currents in this area is essential to understanding where the pollution goes."