Arctic ozone levels in never-before-seen plunge

- Published

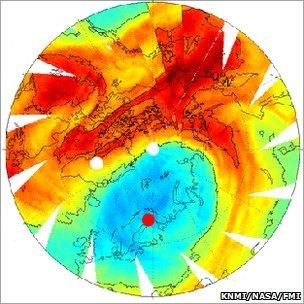

Long a consideration in the Antarctic, ozone levels in the Arctic are now a cause for concern

The ozone layer has seen unprecedented damage in the Arctic this winter due to cold weather in the upper atmosphere.

By the end of March, 40% of the ozone in the stratosphere had been destroyed, against a previous record of 30%.

The ozone layer protects against skin cancer, but the gas is destroyed by reactions with industrial chemicals.

These chemicals are restricted by the UN's Montreal Protocol, but they last so long in the atmosphere that damage is expected to continue for decades.

"The Montreal Protocol actually works, and the amount of ozone-depleting gases is on the way down, but quite slowly," said Geir Braathen, a senior scientist with the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), which co-ordinates ozone data globally.

"In the meantime, we have some winters that get much colder than before and also the cold periods last longer, into the spring," he told BBC News.

"So it's really a combination of the gases still there and low temperatures and then sunshine, and then you get ozone loss."

Dr Braathen was one of a number of scientists presenting the findings at the European Geosciences Union (EGU) annual meeting in Vienna.

'Sun screen'

The destructive reactions are promoted by cold conditions (below -78C) in the stratosphere.

While this is an annual occurrence in the Antarctic, where the annual depletion has garnered the term "ozone hole", the Arctic picture is less clear, as here the stratospheric weather is less predictable.

This winter, while the Arctic was unusually warm at ground level, temperatures 15-20km above the Earth's surface plummeted and stayed low.

"The low temperatures were not that different from some other years, but extended much further into March and April - in fact it's still going on now," said Farahnaz Khosrawi, an ozone specialist at the Meteorological Institute at Stockholm University, Sweden.

Another, Dr Florence Goutail from the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), put the 2010/11 winter in context.

"Usually in cold winters we observe that about 25% of the ozone disappears, but this winter was really a record - 40% of the column has disappeared," she said.

The longer and colder Antarctic winters often see 55% of the ozone depleted.

However, this has hardly any impact on human health, as the region is largely uninhabited - only the southern tip of South America sometimes comes under the ozone hole.

But in the Arctic, the situation is different.

Over the last month, severe ozone depletion has been seen over Scandinavia, Greenland, and parts of Canada and Russia.

The WMO is advising people in Scandinavian countries and Greenland to look out for information on daily conditions in order to prevent any damage to their health.

Loss of ozone allows more of the Sun's harmful ultraviolet-B rays to penetrate through the atmosphere. This has been linked to increased rates of skin cancer, cataracts and immune system damage.

"With no ozone layer, you would have 70 times more UV than we do now - so you can say the ozone layer is a sunscreen of factor 70," said Dr Braathen.

Snow fall

Ozone depletion is often viewed as an environmental problem that has been solved.

The Montreal Protocol, established in 1987, and its successor agreements have phased out many ozone-depleting chemicals such as the chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) that used to be in widespread use as refrigerants.

Ozone data were captured using satellites and weather balloons

Use of some continues at a much lower level, with poorer developing countries allowed more time in which to switch away from substances essential to some of their industries.

But even though concentrations of these chemicals in the atmosphere are falling, they can endure for decades.

In polar regions, the concentration of ozone-depleting substances has only fallen by about 10% from the peak years before the Montreal Protocol took effect.

In addition, research by Markus Rex from the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany suggests that winters that stand out as being cold in the Arctic stratosphere are getting colder.

"For the next few decades, the [Arctic ozone] story is driven by temperatures, and we don't understand what's driving this [downward] trend," he said.

"It's a big challenge to understand it and how it will drive ozone loss over coming decades."

Projections suggest that the Antarctic ozone hole will not fully recover fully until 2045-60.