How astronaut training has changed

- Published

No detail of Nasa missions went unpractised - over and over again

Steely-eyed, unflappable top guns of the era: the first people to be sent into space were among the most rigorously trained people on the planet.

Not that you'd know it from the opening passage from 1959's Outline of the Nasa Astronaut Training Program: "The primary role of the astronaut is to contribute to system reliability by performing emergency functions in the event of failure of the automatic systems."

It depicted the earliest US astronauts as little more than cargo that could push a button in a pinch.

Even by the time Yuri Gagarin made his famed flight, he had to enter a secret code into a keypad in order to take control of his craft; the story goes that the measure was introduced because no one then knew if spaceflight would drive a man mad.

But what training had the Mercury Seven, and Gagarin's 20 fellow cosmonauts, undertaken? How to prepare for the completely unexplored rigours of space travel?

"Both were dealing with unknowns at the time before they launched their first people into space," said UK-born astronaut Piers Sellers.

"So they tried to cover all their bases - but it ended up that they covered their bases a little differently," he told BBC News.

Nasa astronaut Sunita Williams talks about training for her 2006 trip to the International Space Station

In both cases, the best of the nations' pilots were selected (or at least the ones with comparatively small statures, to fit in comparatively small spacecraft).

Yet the Americans, it seems, thought of space travel as a matter of extreme machines, while the Russians considered it a matter of extreme environments.

"The [Russians] tapped a group that had worked on a lot of high-altitude studies during the war," said Cathleen Lewis, a space historian at Washington DC's National Air and Space Museum.

"They were looking at high-altitude physiology and this was another interesting case to prepare for," she told BBC News.

But Dr Sellers said that it was also about sheer fortitude.

"For Gagarin and his friends...they spent a lot of time doing very punishing, physical endurance sort of traning," Dr Sellers said.

"They thought launching a man was going to be absolutely miserable and hateful, so they had absolutely brutal runs in centrifuges, oxygen-deficient atmospheres and things like that… They generally tortured them."

Dirty fingernails

What seems clear is that the American training programme seemed to prepare the astronaut candidates for a wider variety of unexpected outcomes.

For one thing, the American plan from the outset was to land their capsules in the open ocean, the contingencies of which were the cause of much water-borne training.

That meant not just scrambling out of the craft, but also training for survival on the ocean should they come down far from where they were expected.

And what about the event of missing the ocean entirely? Nasa astronauts were treated to full-scale desert and jungle survival training too.

H Morgan Smith led Nasa's jungle training in the mid-1960s, and in an interview in 2002 revealed there may have been an earthier benefit to the survival training.

"By the time you got through spending a million dollars on a man in training and all the technological devices, he deserved to have a few minutes and a couple of dollars of practical hands-on, dirty-fingernails, type of training," he said.

Like much of the Soviet space programme itself, detailed accounts of the preparedness training are rare and unreliable - but in terms of landing in a hostile environment, we know that Gagarin had at least a pistol in Vostok's emergency kit.

In time, as spaceflight became less novel, the astronaut corps was made up less of hardened test pilots and more of academics by training.

By the time of Nasa's 1967 recruitment drive, the average number of college years under an astronaut's belt had jumped from a 1959 level of just over four to 8.3; the civilian scientist-astronaut was taking hold, and that 1959 definition of an astronaut's role was a distant memory.

But the steely-eyed test pilots had their say, too: as mock-up after mock-up of various space capsules were provided and run through mission profiles step by detailed step, the astronauts fed back design ideas to the engineers.

And the trainers fed back ideas to the astronauts; when it became clear that navigation in space would be most reliable if done by the stars, the Mercury astronaut corps went back to astronomy class.

Eventually a mock-up of the capsule was placed inside Morehead Planetarium in North Carolina, where full flight plans were run through with the backdrop the astronauts would see in space.

Buzz Aldrin had just minutes of practice at being weightless before he tried it for days

One thing that couldn't be simulated, though, was genuine weightlessness. The Mercury crew were run through the parabolic flights that allowed less than a minute of free-fall that simulated weightlessness - sometimes with a mock-up capsule on board.

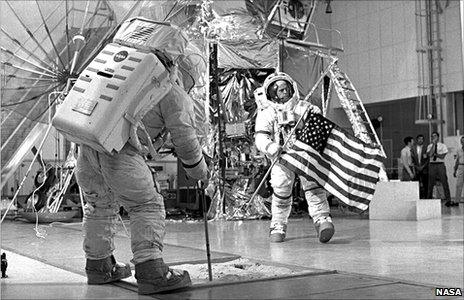

By the time of the Apollo missions, a system of cables and pulleys on an inclined plane was designed to allow trainees to get a feel for gravity one-sixth that of Earth - the same feeling the Moon's surface would provide.

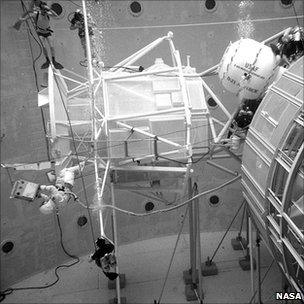

But what has served legions of astronauts has been the world's largest indoor pool: the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory at the Johnson Space Center in Texas.

Fully-suited astronauts can be weighted such that they neither rise nor sink in the best Earth-bound approximation to the weightlessness of space.

The pool holds full-size mockups of the space shuttle and even modules of the International Space Station.

And as computing power has grown up alongside the space programme, another training trick has taken hold.

Dr Sellers explained that many people are surprised by how much astronaut training now relies on virtual reality, particularly for tricky tasks like the spacewalks that are now routine, and involve an increasing amount of robotics.

The Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory is a pool with a volume of over 23 million litres

"Training has changed; the task has changed from the first flights," he said. "Instead of just piloting a capsule around the world, with the shuttle we have a very very complex spacecraft with a lot of systems."

Even the role of pilot has radically changed with the advent of the space shuttle, Dr Sellers said.

"It behaves like a rocket on launch, like a spacecraft in orbit and a very complicated glider on landing - so there's a lot to master."

But Suni Williams, the woman who has spent the longest continuous time in space, says that we've learned not only how to prepare astronauts for their journey, but also to keep them in shape as they spend longer and longer in space.

"Getting ready for a flight, you're probably in the best shape of your life - but coming back is another story," she told BBC News. "You have to understand, every moment you're in space your bone density and your muscle mass is depleting, because you don't need it.

"Every single day you need to try to get yourself back to where you were before you left."

As such, programmes of exercise and even devices to simulate the downward pull of gravity are now standard on the ISS.

But some things about training, Captain Williams said, haven't changed a bit - like the giant centrifuges that have been the staple of test pilot training for nearly as long as piloting itself.

These swing passengers around on the end of a long arm designed to simulate the increased gravitational - or "G" - forces of spaceflight.

"Before a shuttle flight, if you're a first time flier, we go in the centrifuge just to make sure everybody knows what the 'G-profile' will be like when you're coming back home.

"I wouldn't say it's a lot of fun - they put a camera on you so you see what you look like when you're pulling a lot of G's… But it's good training."