Dino crater focus for ocean drilling plans

- Published

The Chikyu can drill up to 6km deep into the seabed

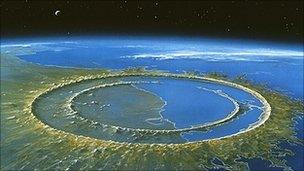

A plan to study the Chicxulub crater by boring 1.5km into the sea bed is among the highlights of ocean drilling projects proposed for the next decade.

Chicxulub, in Mexico, was carved out by the asteroid strike that killed off the dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

The Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP) also plans expeditions to study earthquakes and ancient climate, and says the need is greater than ever.

Another long-term aim is to penetrate the Earth's mantle for the first time.

IOPD scientists were outlining their plans at the European Geosciences Union (EGU) annual meeting in Vienna.

However, they cautioned that funding needs to be secured for the next generation of expeditions.

Kiyoshi Suyehiro, president and CEO of the IODP international consortium, said he hoped to step up earthquake-oriented research around Japan's coasts in the light of last month's devastating Magnitude 9.0 Tohoku quake and subsequent tsunami.

"We are in the process of talking to funding agencies about the direction that should be taken," he said.

"[Japanese research ship] Chikyu has so far been involved in trying to understand seismogenesis in southwestern Japan, which will also experience Magnitude 8-class earthquakes in years to come.

"So we are forming an IODP science team to plan quickly for drilling in the region that produced the recent quake."

The Chikyu, uniquely among scientific drilling vessels, is equipped with "riser" equipment designed to allow penetration 6km into the sea bed.

Its recent work has focussed on the Nankai Trough, a region off Japan's coast with a history of producing major tsunami roughly once every century.

The long-term plan is to place instruments in boreholes in the earthquake-producing area, enabling real-time monitoring in three dimensions of the subduction zone where one of the Earth's great tectonic plates is sliding beneath its neighbour.

Getting connected

More research into earthquakes and other violent events is one of four main areas slated for inclusion in the IODP's next scientific plan, to run from 2013-2023.

The others are:

climate and ocean changes,

life within the ocean floor and

understanding connections between events deep inside the Earth's crust and the surface.

A draft of the plan was recently agreed by researchers at a workshop in Germany, and is due to be published within about a month.

As well as the desperate need to get to grips with earthquakes, Professor Suyehiro also highlighted an urgent need for better data on past climate change in order to improve projections into the future.

"Ocean acidification, climate change, the effects on ecosystems and society - this is another area that requires deep understanding, and we cannot waste time in finding out how they are affecting our lives," he said.

As well as the Chikyu, IODP projects have access to the US vessel Joides Resolution, while the European Consortium for Ocean Research Drilling (Ecord) will commission "mission-specific platforms" as required.

Catherine Mevel from Ecord's management agency in Paris said the new plan had two foci of specific interest to Europe.

"One is the Arctic - we need to understand the tectonic evolution of the Arctic basin because it has a strong influence on global climate change," she said.

"There are gas hydrates trapped in margins that might be released into the atmosphere if the climate warms too much."

Professor Mevel also highlighted plans to drill in the Mediterranean, whose sea floor she described as an "archive" of European climatic history over the last few million years - and a potential source of raw materials such as lithium.

"Also, the Mediterranean is the most tectonically active part of Europe and has a long history of devastating geohazards - landslides, earthquakes, tsunami - and we want to instrument boreholes for long-term monitoring, because it's really key to understanding these active processes."

The plan also calls for renaming the project the International Ocean Discovery Program - retaining the current acronym.

Unique crater

One project that could be up and running by 2013 is an attempt on the Chicxulub crater in Mexico - created by an asteroid strike thought to have ended the age of the dinosaurs about 67 million years ago.

Although boreholes have been sunk on the portion of the crater that is currently on dry land, Joanna Morgan told EGU meeting delegates that the seafloor part had not been touched.

The sunken parts of the crater could yield the secrets of how exactly the dinosaurs met their end

"Chicxulub is the only impact crater on Earth with a peak ring," the Imperial College, London researcher said.

Peak rings are features observed inside large craters on the Moon and on other planets.

The smallest craters are just bowls, with nothing in the middle. Larger ones tend to have a peak in the centre - and when they get bigger still, that central peak becomes a ring.

The Chicxulub structure is known from seismometry, but Dr Morgan said drill cores were needed to take the research a step further.

"We should get about 900m of peak ring material," she said.

"Something very strange has happened to these rocks during the impact event - this will tell us where they're from and what short of shock pressure they were subjected to during the impact."

The cores will also be scoured for evidence of unusual life-forms that might have arisen in the unusually hot and stressed environment.

Investment returns

Ocean drilling for science has a long history, dating back to the US Deep Sea Drilling Project, initiated in 1966.

Current programmes are run internationally in order to promote scientific excellence and cut costs.

Even so, it can be incredibly expensive. Operating the Chikyu can cost $200,000 (£120,000) per day.

In a global recession, governments will have to decide whether they want to prioritise funding at this kind of level.

However, understanding the type of devastation just visited upon the shores of Japan and searching for key energy resources are two cases where investment in central science can potentially return big benefits to societies.

- Published27 August 2010