Destination Titan: Touching a distant world

- Published

Ralph Lorenz recalls the launch of the Cassini-Huygens mission in 1997

A billion miles from Earth, a small saucer-shaped spacecraft emerged from the fiery turmoil of an atmospheric entry.

Seconds later, a set of explosive bolts fired, and its charred heat-shield fell away. A parachute then opened and the craft slowly began its descent, gently buffeted by winds.

With temperatures hovering at a chilly -180C, it finally touched down on the freezing surface of this distant world.

Not the opening chapter of a science fiction novel, but an accurate description of the extraordinary moment on 14 January 2005 when the European Space Agency's Huygens probe landed on the surface of Saturn's largest moon, Titan.

The landing was the culmination of close to 20 years' work for the scientists and engineers involved, and its outcome hung by a thread until virtually the last minute.

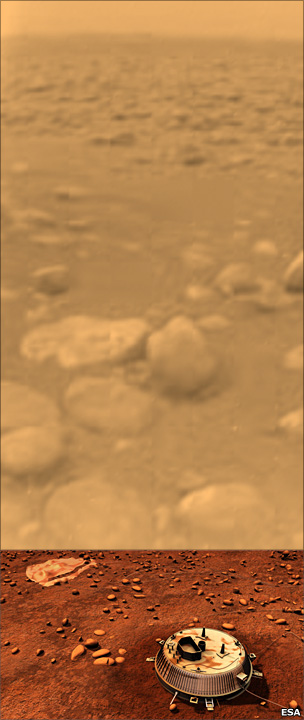

The icy pebbles on Titan's surface and an artist's impression of the probe on the moon's surface

A new documentary, Destination Titan, showing on BBC Four this Sunday, follows the trials and tribulations of a small team of British scientists who had the challenging task of designing the experiment which would make the first ever measurements on Titan's surface.

For Professor John Zarnecki, the Surface Science Package's (SSP) Principal Investigator, the journey to Titan had been a personal odyssey.

Inspired as a boy by seeing Yuri Gagarin when the famous cosmonaut visited London in 1961, Zarnecki longed for a career in space science.

After taking up a post at the University of Kent, the opportunity arose to become part of the joint Nasa-Esa Cassini-Huygens mission.

Cassini was to be the main spacecraft and would go into orbit around Saturn and its moons; Huygens, a landing craft, would ride piggyback on Cassini until its moment came to descend to Titan.

But as Zarnecki recalls, this venture was not his first choice: "The funny thing is we'd initially been backing a project called Vesta, to go and land on an asteroid, and so when this was rejected in favour of Cassini we all felt totally deflated."

The Canterbury team managed to regroup though, and successfully reworked their Vesta proposal for Huygens instead. They would spend the next six years attempting to build an experiment that would work on a surface whose composition at the time was completely unknown. Money was tight. The team enlisted help from Poland, and used Canterbury students to work on different aspects of the SSP.

One of these "cheap labourers" was Ralph Lorenz, who has since become one of the world's major Titan experts.

Lorenz was given the job of designing the Huygens penetrometer, the part of the spacecraft that would make first contact with the surface of Titan.

It was a key component of the SSP, but as he puts it: "Basically, everyone was improvising, because nobody had built anything that had been to Titan before."

Despite some serious setbacks, the experiment was finally delivered, and on 15 October 1997 Cassini-Huygens was launched.

The British team at Cape Canaveral for the launch. John Zarnecki is on the bottom row, far-left

After a journey lasting seven years, the Huygens probe was finally released from its "mothership" on Christmas Day 2004, and began its descent to Titan's surface.

For John Zarnecki and his team, the Huygens landing day was the most nerve-wracking of their careers. A promising signal had initially been detected from Earth-based radio telescopes. However, when the time came for the expected reception of the probe data and pictures, the mission control screens remained blank.

"I just wanted to go away and cry in a corner," Zarnecki remembers. "I had visions of the last 17 years having been wasted."

Soon, though, data began to trickle in, and within hours the world was treated to stunning views of Titan's surface. Especially striking were images of an icy boulder field, taken after landing.

Back in the science lab, the SSP team was frantically analyzing the data from its instrument.

Ralph Lorenz recalls: "The penetrometer record indicated that some kind of crust was present, and then we'd pushed into the surface without much resistance."

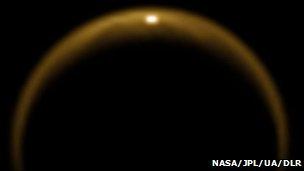

The Cassini spacecraft captures the glint of the Sun bouncing off one of Titan's lakes

Keen to provide a suitable sound bite for the assembled media, it was John Zarnecki who came out with the remark that Titan's surface was "just like Crème Brulee", a scientifically inaccurate but wonderfully descriptive analogy.

In the six years since Huygens touched down on Titan, the Cassini mothership has continued to unveil the secrets of this intriguing world, revealing a place remarkably similar to what scientists think the early Earth might have been like.

Recent radar images have proved beyond doubt that lakes and seas of liquid methane exist on the surface, and that seasonal rain storms of this super-cold substance are occurring over the polar regions of the moon.

If there are future missions to Titan, John Zarnecki acknowledges that he may be "too long in the tooth" to be involved. For now, though, the Huygens lander remains the most distant surface outpost for humanity in the Solar System.

Destination Titan is broadcast on at Sunday, 10 April, at 2200 BST. Stephen Slater is the producer and director of the film.

- Published15 December 2010