Fukushima: As bad as Chernobyl?

- Published

- comments

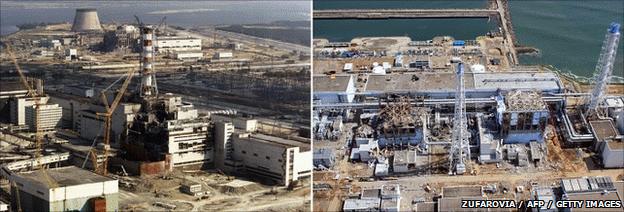

The Fukushima (r) incident is now rated on a par with Chernobyl (l)... but will it prove to be that bad?

Chernobyl is regularly labelled "the world's worst nuclear accident" - and with good reason.

A working reactor caught fire, explosively. Radioactive debris was sent 30,000 feet into the air - the height at which airliners conventionally fly.

Some of that debris came down thousands of kilometres away, in concentrations strong enough to prohibit the eating of meat and the drinking of milk produced locally.

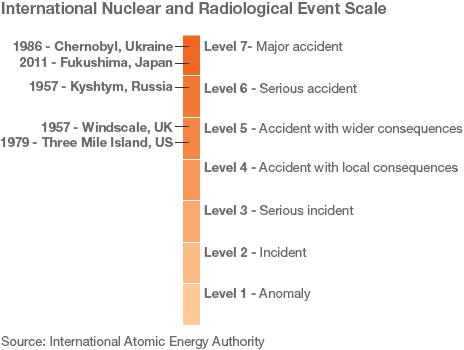

The upgrading of Japan's Fukushima incident to a level seven - the maximum - on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale (INES) puts it on a par with Chernobyl.

And a spokesman for Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco), which runs the plant, suggested it could even end up being worse than Chernobyl.

This, though, appears to be a minority view among engineers - both those who generally support nuclear power, and those who have in the past voiced criticisms.

"The classification of seven means there's a leak of radiation into the wider environment; and although it'll be interpreted as being 'the same as Chernobyl', it's not the same," said Paddy Regan, professor of physics at the UK's University of Surrey.

"The amount of radiation release is a lot less, and the way it's released is very different.

"The Chernobyl fire was putting lots of radioactive material into the atmosphere and taking it over large distances; here, there have been a couple of releases where they've vented [gas from] the reactor, and then released some cooling water."

Don Higson, a retired Australian nuclear safety specialist, was more pithy.

"To my mind, [rating Fukushima equivalent to Chernobyl] would be nonsense," he said.

In the month following the Chernobyl explosion, he said, 134 workers were hospitalised with acute radiation sickness and 31 died.

The equivalent figures for Fukushima are none and none. (Although workers have been taken to hospital with radiation burns, this is not the same as acute radiation sickness.)

Two units

So why the uprating?

What it does not mean is that things have got worse at the plant; in fact, conditions appear to be markedly more stable than in the days following the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, although not completely under control.

Rather, Japan's Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency (NISA) has re-analysed data from the incident and decided that collectively the releases of radioactivity mean it slots into a level seven categorisation.

The manual for agencies using the INES scale, external, published by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), runs to 218 pages.

One of the criteria for evaluating the severity of an incident is the total release of radioactive material.

This is derived by first adding up the amounts of each different radioactive isotope released, then multiplying each by a conversion factor related to the characteristics of that particular isotope, then adding up all of the resulting numbers.

Radioactivity is measured in becquerels (Bq); a million million of these is a terabecquerel (TBq).

A level seven rating is defined as "An event resulting in an environmental release corresponding to a quantity of radioactivity radiologically equivalent to a release to the atmosphere of more than several tens of thousands of TBq of Iodine-131."

NISA puts the Fukushima figure at 370,000 TBq of Iodine-131 equivalent; the Nuclear Safety Commission, which has a more over-arching role in the Japanese system, says 630,000 TBq.

Japanese authorities have acted very differently from their Soviet counterparts in 1986

Either way, it's clearly beyond the threshold for classification as an INES level seven event, although an order of magnitude lower than the 5.2 million TBq released from Chernobyl.

But that tells you nothing about the danger to people.

Becquerels are a measure of the rate of radioactive decay; if one atomic nucleus decays per second, that is defined as one becquerel.

By contrast, sieverts - another unit commonly used during the last month's reporting - measure the likely medical impact of the radiation to which an individual is exposed.

And a huge number of becquerels does not automatically translate into a huge amount of sieverts.

"It's hard to make a comparison between Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima because the radioactive release is different and so is the population," said John Large, a UK-based independent nuclear engineer.

"In Ukraine and Belorussia (now Belarus) it was primarily a rural population, whereas in Japan you've got a highly sophisticated public living in fairly dense population groups.

"And the way the state intervenes is different. With Chernobyl, loads of workers were brought in with no concern for their health - but Japan's a democracy."

In some quarters, Japan's swift decision to establish an exclusion zone, initiate monitoring of people and food, and dispense iodine tablets has received praise - and the volume of advice and warnings issued to the public has been very different from the silence that pertained after Chernobyl, despite criticisms from other quarters over the quality and timing of some of the Japanese advice.

Not spent

Nuclear experts are cautioning, however, that the situation at Fukushima is still very much in play.

Where most attention has centred on reactors 1, 2 and 3, there is also concern about the spent fuel pond in reactor building 4.

In the week following the tsunami, it became clear that the pond was running dry, meaning that fuel rods would have heated up.

This meant likely degradation of their zirconium alloy cladding, the possible release of hydrogen, and - by Tepco's admission - the risk that a nuclear chain reaction could begin.

"The potential for atmospheric release is very large, with 250 tonnes of material sitting in that pond," said Dr Large.

"If you were to have an energetic event you could have a very large release indeed."

The priority is, as it has been all along, to restore adequate coolant to the fuel ponds and the reactors themselves - while hoping that earthquake aftershocks and bad weather do not hamper operations any more.