Fossil from 275 million years ago shows oldest abscess

- Published

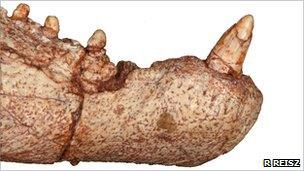

The dark area in the centre of the jaw is the evidence of what would have been a painful abscess

The first-known occurrence of an oral infection has been found in a 275-million-year-old fossil.

The Labidosaurus hamatus fossil, whose detailed analysis using X-rays is described in Naturwissenschaften journal, external, shows signs of an abscess.

The animal was among the first to have just one set of teeth, rather than continuously replacing them.

The adaptation to a plant-based diet would have made them more susceptible, as humans are, to tooth decay and loss.

The find predates the previous earliest-known example of tooth decay by some 200 million years, and also represents the oldest-known infection in a terrestrial vertebrate.

L hamataus was one of the first fully terrestrial reptiles, and with the evolution from a watery to land-based life came a change in diet.

For millions of years, the animal's predecessors had teeth that continuously replaced themselves; new teeth grew into the inner side of the jaw and, when the loosely-connected outer teeth fell out, rose up to take their place.

However, the diet of tough plant matter that land-based reptiles began to eat did not lend itself to weak teeth, so animals like L hamatus over millions of years evolved more deeply-anchored teeth.

Robert Reisz and colleagues from the University of Toronto Mississauga obtained a L hamatus fossil recovered in what is now Texas. Using a commercial computed tomagraphy machine - which provided detailed X-ray data - they were able to image the interior of the fossil's jaw.

They found evidence of a long-lasting bacterial infection and tooth loss - an abscess.

It seems that in animals without the continuous replacement of teeth, oral infections caused by bacteria - which had long since evolved to take up residence in reptiles' mouths - were likely to get worse, rather than be pushed out along with old teeth.

The authors speculate that "our own human system of [having two sets of teeth through life], although of obvious advantage because of its precise dental occlusion and extensive oral processing, is more susceptible to infection than that of our distant ancestors that had a continuous cycle of tooth replacement."

That is, humans have upper and lower teeth that neatly interlock, making it easier to chew, but it is our reptilian forebears' change to firmly fixed teeth that makes us prone to cavities.

- Published30 September 2010