Extinct Australian thylacine hunted like a big cat

- Published

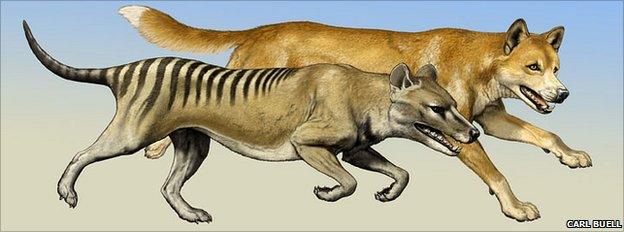

Some think dingoes (background) helped hurry the demise of the thylacine (foreground)

The extinct Australian carnivore known as a thylacine was an ambush predator that could not outrun its prey over long distances, a new analysis shows.

The thylacine has been variously described as a "marsupial wolf" or a "Tasmanian tiger".

This study suggests the latter term might be more appropriate; the animal's hunting strategy was more like that of a big cat than that of a wolf.

Details appear in Biology Letters journal.

Thylacines once roamed mainland Australia, but their numbers declined as humans settled the continent from around 40,000 years ago and as the dingo was introduced around 4,000 years ago.

Eventually, they were confined to the island of Tasmania, which was dingo-free. The species was eventually wiped out during a large-scale eradication effort in the 19th Century and 20th centuries.

Killing tactic

The thylacine was very much a marsupial, and therefore only a distant genetic relative of dogs and cats. But the latest paper deals with the ecological niche it occupied in Australia.

By studying the bones of the thylacine, scientists from Brown University in the US were able to establish that the thylacine was a solitary, ambush-style predator - much like a cat.

Thylacines died out in the early part of the 20th Century.

"Although there is no doubt that the thylacine diet was similar to that of living wolves, we find no compelling evidence that they hunted similarly," said lead author Borja Figueirido, a postdoctoral researcher at Brown, in Providence, Rhode Island.

The researchers compared the thylacine's skeleton with those of dog-like and cat-like species, such as pumas, jackals and wolves, as well as Tasmanian devils - the largest carnivorous marsupials living today.

They found that the thylacine would have been able to rotate its arm so that the palm faced upwards, like a cat.

This increased amount of arm and paw movement would have helped the "Tasmanian tiger" subdue its prey after an ambush.

'Unique mix'

Dingoes and wolves have a more restricted range of arm-hand movement. Their hands are - to a greater degree - fixed in the palm-down position, reflecting their strategy of hunting by pursuit and in packs, rather than by surprise.

However, this is not a hard-and-fast rule. Some cats, like cheetahs, use speed to catch their quarry, while some dog-like species, such as foxes, rely on ambush to catch their prey.

Christine Janis, professor of biology at Brown and a co-author on the paper, said the thylacine's hunting tactics appear to be a unique mix. "I don't think there's anything like it around today," she said. "It's sort of like a cat-like fox."

While some experts believe the introduction of the dingo played a key role in the thylacine's disappearance from mainland Australia, some of the researchers in the latest study are more cautious.

The animals appear to have been similar in several respects - such as their diets - but probably hunted in different ways.

According to Professor Janis, the dingoes may have been "more like the final straw".

The last captive thylacine - known as Benjamin - died in Hobart Zoo, Tasmania, in September 1936.