Anthropocene: Have humans created a new geological age?

- Published

Cities will leave an unmistakeable mark in the geological record of our planet

Human civilisation developed in a cosy cradle.

Over the last 11,700 years - an epoch that geologists call the Holocene - climate has remained remarkably stable.

This allowed humans to plan ahead, inventing agriculture, cities, communication networks and new forms of energy.

Some geologists now believe that human activity has so irrevocably altered our planet that we have entered a new geological age.

This proposed new epoch - dubbed the Anthropocene - is discussed at a major conference held at the Geological Society in London on Wednesday. Yet some experts say that defining this "human age" is much more than about understanding our place in history. Instead, our whole future may depend on it.

The term, the Anthropocene, was coined over a decade ago by Nobel Laureate chemist, Paul Crutzen.

Professor Crutzen recalls: "I was at a conference where someone said something about the Holocene. I suddenly thought this was wrong. The world has changed too much. No, we are in the Anthropocene. I just made up the word on the spur of the moment. Everyone was shocked. But it seems to have stuck."

But is Professor Crutzen correct? Has the Earth really flipped into a new geological epoch - and if so, why is this important?

Back to the beginning

Dr Jan Zalasiewicz of the University of Leicester is one of the leading proponents of the Anthropocene theory. He told BBC News: "Simply put, our planet no longer functions in the way that it once did. Atmosphere, climate, oceans, ecosystems… they're all now operating outside Holocene norms. This strongly suggests we've crossed an epoch boundary."

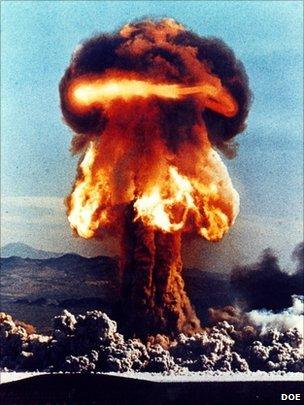

Early atomic bomb tests have left a tell-tale signature in soil

Dr Zalasiewicz added: "There are three ideas about when the Anthropocene began. Some people think it kicked off thousands of years ago with the rise of agriculture, but really those first farmers didn't change the planet much.

"Others put the boundary around 1800. That was the year that human population hit one billion and carbon dioxide started to significantly rise due to the burning of fossil fuels in the Industrial Revolution," he explained.

"However, the really big changes didn't get going until the end of the Second World War - and that's another candidate for the boundary."

To formally define a new epoch, geologists must show how it can be recognised in the layers of mud that will eventually form rocks. As it turns out, there is enormous practical advantage in fixing 1945 as the beginning of the Anthropocene.

"1945 was the dawn of the nuclear age," explained Dr Zalasiewicz. "Sediments deposited worldwide that year contain a tell-tale radioactive signature from the first atom bomb tests in the States".

So, thousands of years from now, geologists (if any still exist) will be able to place their finger on that very layer of mud.

Extraordinary times?

Nonetheless, the choice of 1945 for start of the Anthropocene is much more than just convenient. It coincides with an event that Professor Will Steffen of the Australian National University describes as the "Great Acceleration".

Professor Steffen told the BBC: "A few years ago, I plotted graphs to track the growth of human society from 1800 to the present day. What I saw was quite unexpected - a remarkable speeding up after the Second World War".

In that time, the human population has more than doubled to an astounding 6.9 billion. However, much more significantly, Professor Steffen believes, the global economy has increased ten-fold over the same period.

"Population growth is not the big issue here. The real problem is that we're becoming wealthier and consuming exponentially more resources," he explained.

Humans have made a dramatic impact on many of the planet's ecosystems

This insatiable consumption has placed enormous stresses on our planet. Writing in the prestigious journal Nature, Professor Steffen and colleagues recently identified nine "life support systems" essential for human life on Earth. They warned that two of these - climate and the nitrogen cycle - are in danger of failing, while a third - biodiversity - is already in meltdown.

"One of the most worrying features of the Great Acceleration is biodiversity loss," Professor Steffen said. "Species extinction is currently running 100 to 1000 times faster than background levels, and will increase further this century."

Much of the city of New Orleans is already below sea level

"When humans look back… the Anthropocene will probably represent one of the six biggest extinctions in our planet's history." This would put it on a par with the event that wiped out the dinosaurs.

But perhaps more alarming is the possibility that the pronounced global warming seen at the start of the proposed Anthropocene epoch could be irreversible. "Will climate change prove to be a short-term spike that quickly returns to normal, or are we seeing a long term move to a new stable state?" asked Professor Steffen. "That's the million dollar question."

If the Anthropocene does develop into a long-lived period of much warmer climate, then there may be one very small consolation: the fossil record of modern human society is likely to be preserved in amazing detail.

Dr Mike Ellis of the British Geological Survey told BBC News: "As a result of rising sea level, scientists of the future will be able to explore the relics of whole cities buried in mud".

Preserved buildings

In New Orleans, large areas of the city are already below sea level. The disastrous combination of rising sea level and subsidence of the Mississippi Delta on which it is built suggest that it will succumb at some point in the future.

Although the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts less than a metre of sea level rise over the next 90 years, more than five metres of sea level rise is possible over the coming centuries as the Greenland and West Antarctic ice caps melt.

One application for exploring the changing coastlines of the Anthropocene world is Google Flood. It allows users to raise sea level by up to 14 metres and zoom into street level to see the effects.

Humans are likely to leave behind many markers of their presence, including plastic waste

Sea level rise of this magnitude will mean that the lower storeys of buildings will be preserved intact. Such "urban strata will be a unique, widespread and easily recognisable feature of the sedimentary deposits of the human age", Dr Ellis commented.

Geologists of the future may also hunt for other, more unusual, "markers" of the Anthropocene epoch, such as the traces of plastic packaging in sediments.

But geologists like Dr Mark Williams from the University of Leicester hold much more serious concerns: "One of the main reasons we developed the Anthropocene concept was to quantify present-day change and compare it with the geological record," he explained. "Only when we do so, can we critically assess the pace and degree of change that we're currently experiencing."

Dr Williams added that while the Anthropocene has yet to run its course, "all the signs are that the human age will be a stand-out event in the 4.5 billion year history of the Earth".

- Published23 February 2011

- Published17 September 2010