Lift-off for private space travel dream?

- Published

Watch: A look inside the Space X Dragon capsule

In a gleaming white lobby, with curiously warped furniture familiar from Star Trek, twenty-somethings in shorts and T-shirts amble past like they're on their way to hear a band.

Parked outside, under a brilliant southern California sun, is an electric-powered Tesla sports car.

And even the address has a certain style: Number 1, Rocket Road, Los Angeles.

This is SpaceX, one of a new breed of private ventures promising a revolution in spaceflight - and redefining what is cool about space as well.

As I sign in, two thoughts hit me:

First, that the youngsters are the modern equivalent of the legendary generation that put men on the Moon. Apollo-era ties and slide-rules have been replaced by jeans and iPads.

Second, it's perfectly possible that someone born in the ancient year of 1958, such as your correspondent, might actually be the oldest person in the building.

New generation

I check: there are a few space-age oldies but the average age is a mere 28. Even the boss hasn't quite turned 40.

Elon Musk is dressed like many of his staff: in a black T-shirt and plenty of stubble. He made his fortune on the Internet - where else? He was a founder of the online payments service PayPal.

Now he's busy with not only his Tesla electric car business but also with running one of the most advanced commercial spaceflight enterprises.

SpaceX has already sent its Dragon capsule into orbit on a test flight

His timing couldn't be better: the American space agency Nasa is eager to see private firms fill the role of the space shuttle, flying cargo and astronauts to the International Space Station.

So why space? What is this all about?

Elon Musk is ready for the questions.

"It goes back to when I was at university and I thought about the things that would most affect the future of humanity.

"The three I came up with were the internet, the transition to sustainable energy, and making life multi-planetary.

"I didn't expect to be involved in space because that seemed like the preserve of large governments. But as a result of capital from the internet activity I was able to engage in rocketry."

He speaks rapidly, with occasional pauses during which his look turns distant while another thought forms. The impression is one of a ferocious, impatient intellect. Combined with youthful wit.

Born in South Africa, Musk has degrees in physics and in economics from the University of Pennsylvania. But he knows where his priorities lie.

"I think of myself really as more of an engineer than a businessman. If it wasn't for this company, then I couldn't do the engineering that I want to," he says.

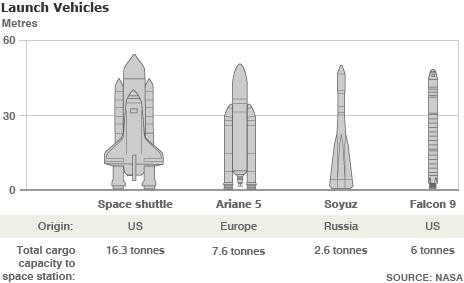

The company's most spectacular achievement came last December when one of his Falcon 9 rockets launched a Dragon capsule into orbit - the first time a private company had ever accomplished this task.

Cheese aboard

On board? A large wheel of Gruyere cheese. Cocooned in a capsule large enough to carry seven astronauts, it circled the Earth twice before splashing down in the Pacific.

Why? Elon Musk looks slightly sheepish. It's because he likes Monty Python. The flight of the cheese was a tribute to the famous cheese shop sketch.

"You've got to have some sense of humour," he says. I wonder if he thinks I'm not amused enough.

Watch: SpaceX CEO Elon Musk on dreams of getting to Mars

In a corner of the factory, beside a frozen yoghurt stand - today's choices: vanilla or blueberry - are giant figures from the movie Iron Man and TV series Battlestar Galactica.

Part of Iron Man 2 was filmed here, the lead role of millionaire-inventor Tony Stark apparently partly modelled on Elon.

There's an easy crossover here between science fiction and science reality, enthusiasts for computer gaming finding an outlet in genuine space travel.

The space capsule that will fly cargo and people is called Dragon and Musk's eventual plan is for it to land under its own rocket power - "landing on a sheet of fire like a real dragon," he says.

Its engines are named Draco like mini-dragons. The motors for the Falcon rockets are called Merlin, partly for the mythical wizard and partly for the engine in Britain's Spitfire fighters.

Long-term ambition

And behind all this, there's a burning ambition: the long-term vision, he says, is Mars and the human need to be "multi-planetary".

"Ultimately we want a system that allows for huge numbers of people and cargo to be transported to Mars and create a self-sustaining civilisation."

Really?

"This is more an aspiration than a prediction," he admits.

"To make them self-sustaining, that may take half a century or a century. But I hope I live to see the first people on Mars and the beginnings of a civilisation."

It prompts me to ask - very courteously, of course - whether he's at risk of trying to run before he can walk. At the time of the interview, SpaceX hasn't yet lifted a human into Earth orbit let alone to another world.

He's ready for that too.

The company occupies a large facility in Hawthorne, California

"We're not trying to get to Mars tomorrow. We are doing a crawl, walk, run approach with gradual improvements in technology."

We end with what I reckon is the key question at the start of this new era of private operators flocking into space: will it be safe?

Elon Musk is emphatic. Private companies are not only better at innovation and at optimising costs - but they'll be safer too.

"I'm confident that the system we design will be safer than any other system before it. I think we need to be at least 100 times better than anything before.

You mean the shuttle?

"Yes."

And this entrepreneur who calls himself an engineer rather than a businessman adds a commercially-minded point:

"As a commercial entity it doesn't pay very well to kill your customers."

He laughs. In fact he's laughed quite a lot during our interview. As someone more used to the steady-voiced traditionalism of Nasa or Esa or the Russian space agency, I find this takes some getting used to.

But the opening up of space to private operators is a kind of revolution. And that means new attitudes, and new styles.

As we part, I ask him to pick his favourite Monty Python film. Life of Brian or Holy Grail? He's stuck. He loves them both, but opts for Holy Grail - because he quotes more from it, he says.

I picture his mind whirring over the technological challenges that lie ahead: how to ensure not only that the next flight is successful - but also that its cargo is as funny as a Gruyere cheese.

- Published5 April 2011

- Published14 February 2011

- Published8 December 2010

- Published11 October 2010