UK technology's magnetic space future

- Published

- comments

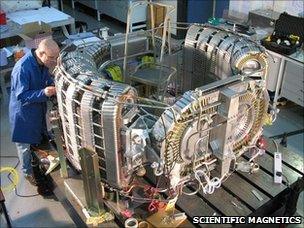

UK engineers spent 12 years working on the device, only to see it dropped from the mission late on

It's thought as many as half a million people crammed the roads and beaches outside the Kennedy Space Center to see Endeavour's final launch.

Thousands more had official guest status and got a slightly closer view from inside the spaceport itself. A magnificent morning ascent for the youngest of the Nasa spaceplanes as it began its final mission - the delivery of the $2bn Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS) instrument to the International Space Station.

There will, however, be a group of British engineers for whom Monday's lift-off was a bitter-sweet moment. These are the people whose technology got dropped from AMS in the year before launch.

For those not familiar with this story, let me back up and reprise events. They have some potentially fascinating implications for deep space travel.

AMS is one of the most expensive science experiments ever put in space - probably the most expensive.

It has taken a group of 600 or so researchers from 16 nations a total of 17 years to prepare it for flight. It promises some dramatic new insights into the origin and make-up of the cosmos.

AMS will do this by studying the storm of high-energy particles (cosmic rays) that are hurled at Earth from the deepest reaches of the Universe.

Critical to its operation is a very strong magnet. As the particles enter AMS, they will bend through this magnet. How they bend reveals their charge, a fundamental property that says a great deal about the nature of those particles and where they came from.

Endeavour climbs into the sky, the AMS packed in its payload bay

The UK at a programmatic level never got involved in AMS, presumably because it was a space station project (and the UK doesn't engage with human spaceflight), but one British company was contracted to build the all-important magnet.

Scientific Magnetics (formerly Space Cryomagnetics) of Culham, in Oxfordshire, external, spent 12 years developing this super-cooled beast, and it was - so the project leaders on AMS told me - a marvel.

It was incredibly powerful and directed its entire field inwards, like an enclosed bubble. From the outside, the magnet appeared as an inert beer can.

This was really important because if you put such a device on a shuttle or a space station and it hasn't been carefully designed, it will start to interact with its surrounding - even try to orientate itself with the Earth's magnetic field. Not what you want on a space vehicle.

But to cut a long story short, the British magnet's super-fluid-helium cooling mechanism meant that it was only ever going to be a short-lived device. And when the space station's life was extended last year to 2020, the AMS project leaders took the decision to remove the UK magnet and replace it with a less powerful, but much longer-lived, Chinese one.

Now, as I say, this is a story with some interesting outcomes.

The British magnet is currently sitting in store at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (Cern), external where AMS was assembled and tested, and there's a lot of interest in seeing its technology put to other uses.

The first of these is astronaut protection. The cosmic rays that AMS is trying to characterise are particles that also represent a hazard to humans in space.

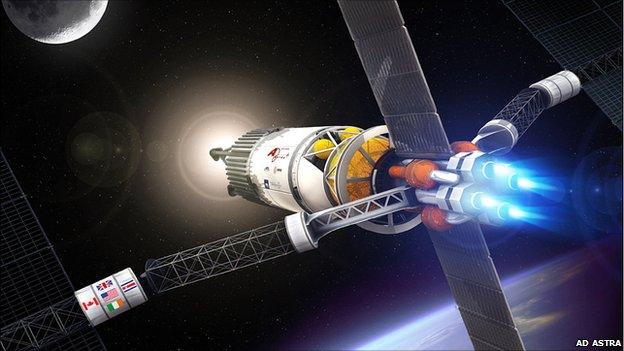

Ad Astra has been running a testbed incorporating British superconducting-magnet technology

When astronauts eventually go beyond the space station - back to the Moon, and on to asteroids and Mars - they will need to shield themselves from these high-energy particles. The idea of using a powerful magnetic field to do this job is being investigated Dr Roberto Battiston, the deputy principal investigator on AMS. He told me:

"We continue to work to understand how this technology could be used for future shielding of astronauts undergoing long exposure, for instance at a Moonbase or on a trip to Mars… because this is by far the most advanced super-conducting magnet-design ever built and completed for a space mission. It is not going to fly but it had everything that would allow it to fly.

"The European Space Agency asked me to submit a proposal for a feasibility study and [Scientific Magnetics] is part of it.

"We would design the magnet in a different way to the AMS one. AMS was designed to have a very strong magnetic field within an inner bore. By modifying the coils and the currents, we can design a magnetic field confined in an external ring surrounding an inner bore that is magnetic-field free. In this internal module will be the habitable part for the astronauts - where they will live. We are talking about something having a diameter of about five to six metres and the length of 10m - surrounded by this magnetic field that is intense enough to bend away cosmic rays coming from deep space."

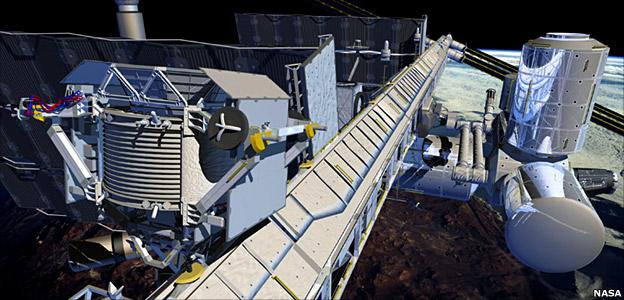

The AMS (left) will sit on the station's truss, or backbone, slightly tilted to look past the giant solar wings

There are immense practicalities to overcome, of course. These special magnets get their strength because they are superconducting. This means running them at cryo-temperatures, which demands a lot of liquid helium.

This has a tendency to boil off over time, limiting the life of your device, which brings us back to AMS. All that said, Professor Battiston is encouraged by the research. He says it should be possible to limit radiation exposure on a Mars flight to something similar to that currently experienced by astronauts on a six-month stay at the space station.

The other big space application for which British magnet technology might be useful is in the plasma rockets that could one day propel all spacecraft.

These rely on the motion of highly excited gases, or plasmas, moulded by magnetic fields to provide thrust. Although they don't give the initial big kick you get from chemical combustion, their supreme efficiency means they can go on thrusting for extended periods, achieving far more acceleration per kilogram of fuel consumed. Proponents of plasma rockets say they could dramatically cut the journey time to Mars from months to weeks.

Scientific Magnetics has already produced a superconducting magnet for a testbed at Ad Astra in Texas, external, the company at the forefront of this propulsion technology.

Steve Harrison from Scientific Magnetics told me:

"These rockets use radio frequency heating to generate the plasma and then the magnets contain the plasma in the same way they do in a tokomak fusion reactor. The magnets are profiled such that they form a sort of nozzle out the back; and because the plasma is expanding and supersonic, it flies out and gives you thrust. For the system Ad Astra has been testing for the last two years, we designed and built the super-conducting magnet."

Similar obstacles to the magnetic shield prevent immediate adoption of the propulsion application as well, especially if the propulsion magnets incorporate cryogenic liquids, but both concepts are definitely worth watching for the future.

Magnet technology could provide both radiation shielding and propulsion on future deep-space vehicles