UK teams assess Europe's 2018 Moon lander

- Published

- comments

Three British teams have been asked to spec key instrumentation for Europe's proposed Moon lander, external.

The European Space Agency (Esa) is planning to send a robot to the lunar south pole in 2018.

With a mass just shy of a tonne, the spacecraft would demonstrate automated precision navigation in picking out a safe place to put down.

And, once on the surface, it would release a little rover to trundle across the regolith (soil).

The UK teams will help refine what science the mission pursues and the kit needed to acquire the data.

The Moon, as I think I've said before, is a sexy place again.

For 30 years following the Apollo programme, it was kind of forgotten.

Everyone looked outwards to distant worlds, like the moons of Jupiter and Saturn, as being the fun locations to go.

But recent spacecraft observations, external have indicated that some polar craters on the Moon probably hide vast reserves of water-ice deep in their shadows, and this has reawakened interest in Earth's satellite.

The new appetite for lunar science has been driven in part by the prospect of humans going back there sometime soon.

Although when exactly this might happen is anyone's guess, as the US has now formally cancelled its Moon-bound Constellation programme.

Nonetheless, a train of orbiting and surface probes is set to visit the Moon in the coming years, and these visitors promise fascinating new revelations about the neighbour we thought we knew inside-out.

Esa's proposed lander is not a "science mission" as such; rather, it is a pathfinder for human exploration.

What I mean by this is that the science it will undertake will be geared to gathering information which could help humans operate on the surface.

So, it will be looking for any local resources that could be used by future astronauts, and the lander's instruments would also assess the lunar environment to understand the risks it could pose to those explorers.

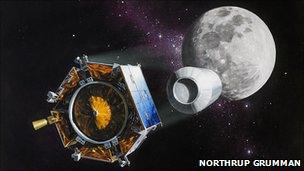

LCROSS impacted the surface to kick up water-ice deposits so they could be seen from orbit

Moon dust, for example, is considered a major hazard. The fine particulate material will compromise seals and electrical contacts, and if breathed in would cause respiratory problems.

In this vein, a consortium led by the Open University, external has been asked to spec the Esa lander's volatiles analysis package; a group led by SEA, external will assess the lunar dust analysis package; and the Mullard Space Science Laboratory, external (MSSL) will work with a number of other groups across Europe in defining the dust environment and plasma package.

The OU's involvement is particularly interesting because it calls on the expertise of Professor Colin Pillinger. Most people will know Colin from the Mars Beagle 2 lander project, but in his younger days he worked on the Moon rocks returned by Apollo and Soviet Luna missions, external.

"Back then I was one of the fresh-faced people. Esa wants the heritage of someone who's been there and got the T-shirt, so to speak," he told me.

"We will evaluate the package which will do the prospecting for the volatiles, which will almost certainly include H2O. The questions are, how much is there and can you get it out? It's pretty clear there are several sources of H2O - it's been implanted by the solar wind, and there're meteorite and comet impacts, for example.

Colin Pillinger (near) worked on the Moon rocks returned by the Apollo and Luna missions

"We saw from Nasa's LCROSS mission that if you impact something on an area you can create enough heat to put things into a gas phase that can then be seen from orbit. Now Esa wants to go with a pinpoint lander and look at all of this in detail. In our study, we'll consider the science questions that have to be addressed and then put forward a design idea for the instrument package."

The British teams have been engaged even though the lander project belongs to Esa's Human Spaceflight Directorate.

As you probably know, the UK does not contribute to Europe's human spaceflight programme and its scientists and engineers are therefore normally shut out of any related activities.

But these particular studies are being funded from the agency's General Studies Programme, and this allows Esa to call on the expertise in countries beyond just those paid up to the directorate. With the UK strong on planetary science, it's handy to have its input.

As to the UK's involvement in the mission proper in 2018 - well, that's a question for the UK Space Agency and what it plans for its membership at Esa. This will be decided at the next Ministerial Council in Italy late next year.

Dr James Carpenter, the lunar lander project scientist at Esa, told me: "At present, we have Germany, Portugal, Spain and Canada involved, with a few others maybe coming in soon. Following the studies we've done, the mission in its entirety will be presented to the next Ministerial conference. If the member states think it's something they want to invest in, then they'll do so."

The fully formed European lander concept will be presented to space ministers next year

- Published16 September 2010

- Published22 October 2010