Iceland volcano pumps a different ash

- Published

Parts of Iceland have been draped in a thick fog of ash, with flights banned close to Grimsvotn

The eruption of the Grimsvotn volcano in Iceland is huge, but it is not expected to cause the kind of disruption we saw last year when Eyjafjallajokull blew its top.

The Eyjafjallajokull eruption, in April 2010, caused the largest closure of European airspace since World War II, with losses estimated at between 1.5bn and 2.5bn euros (£1.3-2.2bn).

Experts say the material produced this time is likely to be in the form of larger grains that will fall out of the atmosphere much faster.

Prevailing weather patterns currently also mean this eruption plume will stay away from a great swathe of European airspace.

What is more, the aviation and meteorology agencies believe they now have the tools in place to manage the situation more effectively.

Eyjafjallajokull was an unusual eruption.

Initial activity melted ice lying above the volcano, with the meltwater running down into the crater and mingling with hot lava, creating an explosive mix.

Long after the event, scientists confirmed that the Eyjafjallajokull cloud contained exceptionally fine and sharp particles that would have melted inside jet engines, clogging them, and would have sandblasted other engine components and windscreens.

Last month, releasing these results, a Danish/Icelandic scientific team said the decision to close airspace had been "absolutely right".

Explosion damped

Grimsvotn, too, is covered in ice. But Dr Clive Oppenheimer from the University of Cambridge suggested the explosive generation of fine particles was unlikely this time.

Grimsvotn has laid ash thick enough on Reykjavik streets that footprints can be seen

"We've got that ingredient; we've got an ice cover on Grimsvotn," he said.

"However, I think the composition of the magma favours a coarser ash, which means it will perhaps fall out of the sky much more quickly than was the case with Eyjafjallajokull."

The basalt in Eyjafjallajokull had a high silica content, which gave it the explosive capacity to produce small sizes of ash able to hang in the atmosphere for long periods.

But Grimsvotn is different.

"The magma in Eyjafjallajokull was what is called a trachydacite," explained Dr Dave McGarvie, a volcanologist from the Open University.

"That had about 63% silica compared to the 50% silica in Grimsvotn. The material in Eyjafjallajokull, simply put, was much stickier - it's like comparing treacle to water.

"When you have those conditions, you're going to blast it apart much more and produce much finer particles," he told BBC News.

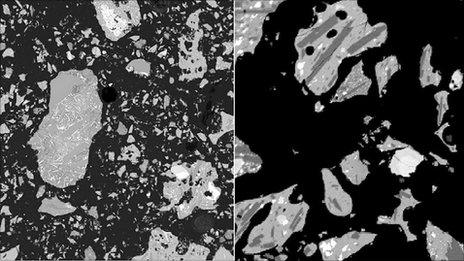

Grimsvotn is thought to produce a coarser ash similar to that found in the later stages of the Eyjafjallajokull eruption (R) rather than the small (sub-micron) and very abrasive particles (L) that Eyjafjallajokull initially emitted

Although Grimsvotn's larger particles should come to Earth faster, it is a bigger event.

In its earliest phase, over the weekend, it was emitting 10-100 times more material per second than Eyjafjallajokull.

That was seen in the height reached by the plume, which climbed to 17km (11 miles), compared with the 6-9km altitude reached by the Eyjafjallajokull ash.

At the moment, the weather is not behaving in a way that will bring substantial quantities of ash towards European airspace.

But if that situation changes, the meteorological agencies say they are ready for it.

The UK Met office, which runs Europe's Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre, has a new ground-based radar in Iceland to get more information about plume behaviour.

More lidars, which use lasers to analyse aspects of the ash cloud such as its density, have also been deployed.

The Met Office believes the lessons learned mean a much more calibrated response will be possible in future, rather than the blanket "no fly" advisories that were issued in 2010.

- Published24 May 2011

- Published25 April 2011