Electron particle's shape revealed

- Published

Electrons (blue) orbit the nucleus of an atom in this schematic

The most accurate measurement yet of the shape of the electron has shown it to be almost perfectly spherical.

Electrons are negatively-charged elementary particles which orbit the nuclei of atoms.

The discovery is important because it may make some of the emerging theories of particle physics - such as supersymmetry - less likely.

The research, by a team at Imperial College London, is published in the latest edition of Nature journal.

In their scientific paper, the researchers say the electron differs from being perfectly round by a minuscule amount.

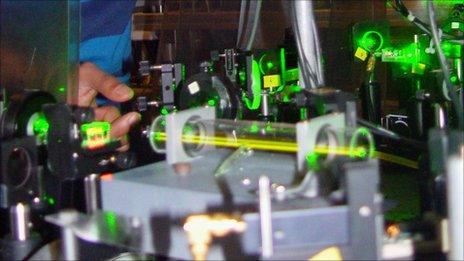

"Conventionally, people think that the electron is round like a little ball. But some advanced theories of physics speculate that it's not round, and so what we've done is designed an experiment to check with a very, very high degree of precision," said lead author Jony Hudson, from Imperial.

The current best theory to explain the interactions of sub-atomic particles is known as the Standard Model. According to this framework, the electron should be close to perfectly spherical.

But the Standard Model is incomplete. It does not explain how gravity works and fails to explain other phenomena observed in the Universe.

Egg off the menu

So physicists have tried to build on this model. One framework to explain physics beyond the Standard Model is known as supersymmetry.

However, this theory predicts that the electron has a more distorted shape than that suggested by the Standard Model. According to this idea, the particle could be egg-shaped.

The researchers used lasers to measure the shape of the electron

Researchers stress that the new observation does not rule out super-symmetry. But it does not support the theory, according to Dr Hudson.

He hopes to improve the accuracy of his measurements four-fold within five years. By then, he said, his team might be able to make a definitive statement about supersymmetry and some other theories to explain physics beyond the Standard Model.

"We'd then be in a position to say supersymmetry is right because we have seen a distorted electron or supersymmetry has got to be wrong because we haven't," he told BBC News.

Dr Hudson's measurement is twice as precise as the previous efforts to elucidate the shape of the electron.

Future prospects

That in itself does not alter scientists' understanding of sub-atomic physics, according to Professor Aaron Leanhardt of the Unviersity of Michigan in the US.

But the prospect of improved measurements and the potential to shed light on current theories of particle physics has made the research community "sit up and take notice".

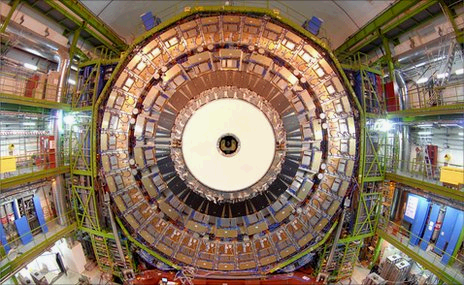

The Large Hadron Collider is searching for signs of supersymmetry

"A factor of two doesn't change the physics community's general opinion of what's going on," he told BBC News.

But he added that improved measurements could start "constraining the possible theories, and what could be discovered at the Large Hadron Collider at Cern and what you might expect in cosmological observations."

Current theories also suggest that if the electron is more or less round, then there ought to be equal amounts of matter and anti-matter - which, as its name suggests, is the opposite of matter.

Instead, astronomers have observed a Universe made up largely of matter. But that is an observation that could be explained if the electron were found to be more egg-shaped than the Standard Model predicts.

Although the shape of the electron could have an important bearing on the future theories of particle physics, Dr Hudson's main motivation is simply curiosity.

"We really should know what the shape of the electron is," he said.

"It's one of the basic building blocks of matter and if this isn't what physicists do I don't know what we should do".

- Published7 April 2011

- Published2 August 2010