Fishing: A story of less for more

- Published

- comments

Paying fishermen to fish doesn't pay.

That's the conclusion of a report, external just out which looks at how profitable European fisheries would have been over the last 20-odd years without subsidies, and compares those numbers against what actually happened.

(The report is formally published in the journal PLoS One, external, although it's not on their website at the time of writing - there's a pre-publication document here, external that gives the gist.)

Although the North Sea is the focus, the conclusions may well be applicable everywhere.

Subsidising fishermen means they continue fishing even after stocks begin to plummet, because a substantial share of their income is now coming from the subsidy rather than from profits on fishing.

And the sums involved are quite compelling.

"208m euros (£180m, $293m) paid out by the EU in fisheries subsidies resulted in North Sea fisheries actually being less profitable by a massive 71m euros (£62m, $100m)," the researchers write.

Subsidising boats does sometimes boost the short-term economics because you can catch more of a profitable prey; but eventually, the needle always turns, the researchers report.

This is just the latest iteration in a long-running but little-told story.

And the conclusions tie in with a big World Bank study, The Sunken Billions, external, released back in 2008, which concluded that overfishing was costing the global economy $50bn (£30bn) per year.

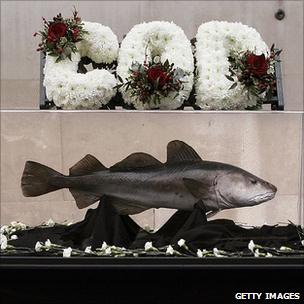

In the North Sea, cod is one of the species closest to the end of the line

Basically, too many boats are on the water - twice the number needed to catch the amount of fish being hauled in each year - and operating those extra boats costs money.

As many are being kept afloat by subsidies, the cost, in this equation, is borne by the public purse.

Subsidies do not make the sexiest or most fashionable aspect of fisheries - in contrast to discards, they're not the kind of thing that environmental campaigners or TV chefs will get too excitable about.

But some academics would argue they are the single biggest thing needing reform if the progressive degradation of fish stocks around the world is to be halted.

Just this week, EU Fisheries Commissioner Maria Damanaki announced, external that about two-thirds of stocks in European waters are overfished - an improvement on the previous year's data, to be sure, but still a striking indication of degradation in what's supposed to be an environmentally aware part of the planet.

Just how badly fisheries are faring globally is a live issue, opened anew by a recent paper suggesting depletion is not as bad as previously reported - although those conclusions are hotly debated, external.

But no-one's saying all is rosy.

Within Europe, a relatively new venture called fishsubsidy.org, external is turning up some fascinating and revealing statistics on how much is being spent, and for what, on the fishing fleet.

Some of the highlights involve the dual payments that some owners have received - a subsidy for buying or building a boat, and then another one for scrapping it.

In one case, the interval between the two payments was a mere 17 days.

Subsidies have declined within the EU; and in principle at least, money isn't paid any longer for new boats.

But the issue of what constitutes a subsidy remains somewhat ill-defined.

A few years ago, in Spain making a radio documentary, external on fisheries, a skipper told me that he no longer received any subsidies.

But a bit later, he said the fleet bought diesel at specially cheap rates.

Part of the issue is that national governments can all say "well, if we don't subsidise our fleet, neighbouring countries will.

"Their fishers will catch more than ours, our industry will decline, and we'll lose votes in fishing communities."

And if they all do it... well, they all have done it, and that's how we got where we are.