Robots and humans target asteroids

- Published

- comments

Nasa's asteroid sample-return mission will cost about a billion dollars to mount

There were two key announcements this past week relevant to the human exploration of space beyond low-Earth orbit and the space station.

The first was the confirmation by Nasa that it would press ahead with the development of a Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle (MPCV) based on its "cancelled" Orion concept.

Orion, originally conceived under the US agency's now defunct Constellation programme, was to be equipped with the systems needed to sustain astronauts on long journeys away from our planet. The MPCV (Orion in all but name) will be similarly equipped.

The other important bit of news was the selection of Osiris-Rex [2.5MB PDF], external to launch in 2016.

This robotic mission of Nasa's will travel out to an asteroid called 1999 RQ36; its arrival is expected in 2020. After some remote-sensing of its target, Osiris-Rex will then attempt to pick up some grit and dust from the space rock before returning those samples to Earth for study in labs across the world.

What links these two announcements? Well, President Obama has set Nasa the objective of getting humans to an asteroid by 2025. The crew will undertake that venture in the MPCV, and their encounter will benefit from the lessons learned on Osiris-Rex.

All this ought to be viewed with some relish. As I've written on many previous occasions, asteroids are anything but dull, dumb rocks.

In exploration terms, these objects are stepping stones to even more distant destinations. The 2025 asteroid expedition would be followed at a later date by a mission to circle Mars, perhaps even to land on one of its two moons, before trying to get down on to the Red Planet's surface itself.

Asteroids are also key science targets right now. It's oft said that they are left-overs from the formation of the Solar System - bits of rubble that never quite got incorporated into planets proper. The more pristine examples out there hold critical clues to those early formation processes and the materials involved.

Asteroids will be a resource one day, too. Some contain large amounts of platinum and other precious metals; some contain substantial quantities of water. These rocks could be used like filling stations - their water could be split into hydrogen and oxygen to make rocket fuel for the next leg of an interplanetary journey.

And asteroids are the potential foe we need to understand. There could be a big rock out there that we haven't yet identified which is on a collision course with Earth. We must learn how these mountains of rock are constructed in order to develop the best strategies for deflecting any that pose a serious risk of impacting our home planet. We don't want to go the same way as the dinosaurs.

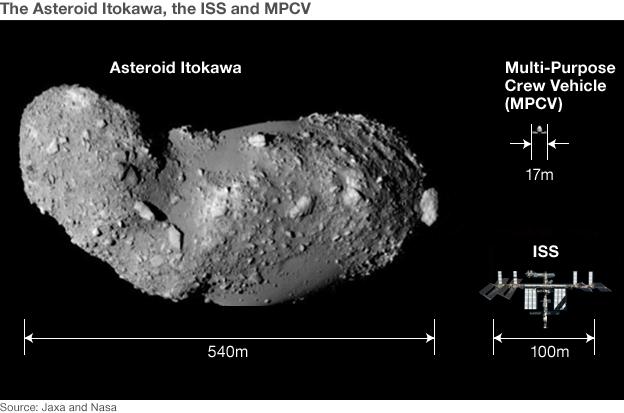

Itokawa is quite small compared with some of the asteroids the MPCV could visit

On the issue of Earth protection, one of the tasks for Osiris-Rex will be to measure accurately something called the "Yarkovsky effect, external" for the first time.

This describes what happens when an asteroid radiates energy absorbed from the Sun back into space. Releasing heat in one direction nudges the object in the opposite direction. The resulting acceleration is tiny, but over the centuries acts like a weak rocket and could make the difference between a hit or a miss in some circumstances.

But the main objective of Osiris-Rex will be to try to grab a sample from the surface of 1999 RQ36. This is really hard, as the Japanese discovered when their Hayabusa spacecraft visited Asteroid Itokawa.

Most asteroids have crazy, irregular shapes, and exert very little gravitational attraction. Disturbed material has a tendency to float up off the surface, making it more difficult to handle. The Japanese tried to fire a small ball at Itokawa, hoping the impact would kick up dust into their sample collector. It did, but in minuscule amounts.

A lot of effort has gone into working out how to pick up a sample from the surface of an asteroid

The Osiris-Rex team will try a different approach. The spacecraft will push its sample-grabbing mechanism into the asteroid's surface on the end of a long arm.

Michael Drake, of the University of Arizona in Tucson, is the mission's principal investigator. He explains: "On the end of the arm is the sample collection device, which is a rather simple device which looks a bit like a car filter, and we actually blow nitrogen gas into the surface on contact to agitate the surface and collect the sample inside this thing that looks like a car filter.

"It's a very elegantly simple design that Lockheed Martin came up with."

Let's hope it works. Here in Europe, a lot of work has been done on this topic because we have our own asteroid sample-return concept, currently called MarcoPolo-R, external. This is still in competition with other mission ideas at the European Space Agency but, if selected, could launch in about 2021.

Space company Astrium UK has tested a variety of sample-grabbing mechanisms for the MarcoPolo effort. The exercise proved the need to be prepared for every type of surface.

If you go to the asteroid expecting to pick up gravel and pebbles and find only fine sandy material or large boulders - you're in trouble.

Marie Claire Perkinson, a mission design specialist at Astrium, told me: "In the past, people have taken a rather optimistic view of what the regolith, external might be like. That view has been based on what we know of the Moon's surface. But you have to make sure you can handle every type of surface; you have to test your mechanism before you go at all levels.

"We investigated samples that were individual sizes but also mixes of sizes, to see what performance we could get. We found success with a corer mechanism - like a wide-bore drill - with a shutter at the bottom."

This actually highlights one of the advantages of humans over robots in space. For all the intelligence we're now able to program into computers, nothing compares to the astronaut's capability for on-the-hoof decision-making.

Astronauts moving across a small body can make instant decisions, reacting in real-time

Paul Abell, at Nasa's Johnson Space Centre, has been looking at how an astronaut mission to an asteroid might be carried out.

"Asteroids present some real challenges for robotic spacecraft, and having human beings there in direct contact with the asteroid - they're very adaptable and can react to situations," he says.

"Keep in mind that for Hayabusa, the light-delay time for communication was about 32 minutes; it was an object on the far side of the Sun. The robot was doing really well but we were limited by what we could do because of those communications delays.

"When you have humans directly interacting with the surface, they can do things in real time. Humans can look at a rock and perhaps decide to take the sample from underneath the rock."

I'm really looking forward to Osiris-Rex even if its samples won't make it back to Earth until 2023.

What difference the American decision to select Osiris-Rex makes to European thinking on MarcoPolo-R, and whether also to green-light a sample-return mission, is anyone's guess. Antonella Barucci from the Paris Observatory, external is leading the MarcoPolo-R proposal and will be a co-investigator on Osiris-Rex. She believes the American selection supports her cause.

"I think this is good news because this opens up a new era on asteroid research, because in this moment all the major space agencies in the world want to go to a near-Earth asteroid for sample return," she told me.

"It's very important we go to different targets. The Obama declaration to send humans to an asteroid means we must have precursor missions to characterise all these objects; and they are all so different - in shape, gravity, density, in surface structure, regolith and porosity.

"We need to visit several before we recognise their general characteristics."