Climate to wreak havoc on food supply, predicts report

- Published

Areas where food supplies could be worst hit by climate change have been identified in a report.

Some areas in the tropics face famine because of failing food production, an international research group says.

The Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) predicts large parts of South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa will be worst affected.

Its report points out that hundreds of millions of people in these regions are already experiencing a food crisis.

"We are starting to see much more clearly where the effects of climate change on agriculture could intensify hunger and poverty," said Patti Kristjanson, an agricultural economist with the CCAFS initiative that produced the report.

A leading climatologist told BBC News that agriculturalists had been slow to use global climate models to pinpoint regions most affected by rising temperatures.

This report is the first foray into the field by the CCAFS initiative., external To assess how climate change will affect the world's ability to feed itself, CCAFS set about finding hotspots of climate change and food insecurity.

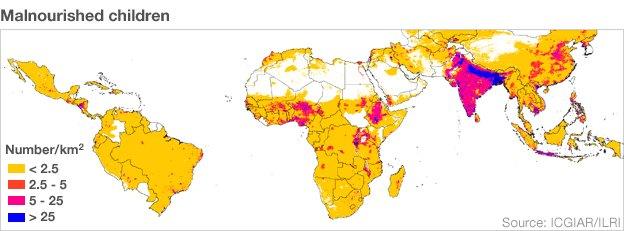

Focusing their search on the tropics, the researchers identified regions where populations are chronically malnourished and highly dependent on local food supplies.

Then, basing their analysis on the climate data amassed by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the team predicted which of these food-insecure regions are likely to experience the greatest shifts in temperature and precipitation over the next 40 years.

Mapping hunger

By overlaying the maps, the team was able to pinpoint which hungry regions of the tropics would suffer most.

With many areas in Africa predicted to become drier, countries such as South Africa which predominately farm maize have the option to shift to more drought resistant crops.

But for countries such as Niger, in western Africa, which already supports itself on very drought resistant crop varieties, like sorghum and millet, there is little room for manoeuvre, explains Bruce Campbell, the director of CCAFS.

"West Africa really stands out as problematic. Burkina Faso, Niger, Mali. They are already dependent on sorghum and millet.

"In many places in Africa you are really going to need [a] revolution in farming systems," he says.

"We need everything we can lay our hands on," said Sir Gordon Conway, professor of international development at Imperial College London.

Governments are aiming to limit the average increase in temperature to 2C by the end of the century, he explained. But if temperatures continue to follow their current trajectories "we are on for a 3-4C increase", Sir Gordon explained.

If this was correct "things get very alarming", the professor said.

Professor Martin Parry, a visiting professor at the Centre for Environmental Policy at Imperial College London, who co-chaired one of the working groups in the IPCC's last climate assessment, responded to the report by saying he thought that CGIAR, the parent body to the CCAFS, had been slow to move into the field of climate change as a key area of research. But he added that this step was very welcome.

But he cautioned: "This gives us a better local picture of where the most vulnerable areas might be… but it doesn't make strong enough connections between the changes in the weather and its impacts on yields."

This made it difficult to plan for adaptations, Professor Parry told BBC News.

- Published10 August 2010