To boldly go beyond the Solar System

- Published

A replica of the Voyager probes is housed at JPL

Keep your voice down, the press officer warns me, as I step inside Nasa's mission control room in California, a centre with an utterly unique role in the exploration of space.

It's almost silent and very dark, here at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena and operators are hunched over banks of consoles.

These are people with an extraordinary job: they provide the sole connection with mankind's most distant creations.

Above us a giant screen is gently filling with numbers, row after row of digits - it's the daily flow of data from an inconceivably remote corner of space.

At the start of each line of figures, there's a three-letter code - VGR - that represents the longest expedition ever mounted in human history.

VGR stands for the pair of spacecraft, Voyagers 1 & 2, launched way back in 1977 and now entering a realm never visited before - the very edge of the Solar System.

As another row of figures nudges its way on the screen, I try to comprehend what they've crossed to reach here.

Waiting game

One measure is that it takes an incredible 16 hours for their radio transmissions to arrive on Earth.

And if the controllers need to send a signal back out to them, it takes the same again - 32 hours in all to fire off a message and get a response.

Guiding me through this is the godfather of the mission, a sprightly professor in his 70s who is still bursting with the same enthusiasm he felt when he began the project in 1972.

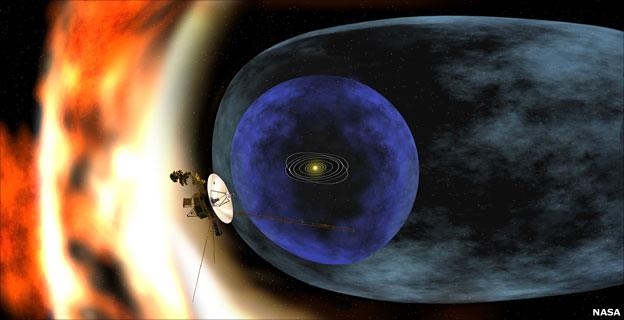

Voyager is approaching the edge of the bubble of charged particles the Sun has thrown out into space

This is Ed Stone, something of a legend in space circles. Few other scientific endeavours have lasted this long and he's followed every twist and turn.

I ask about the distances involved and he can't wait to explain.

"When you feel the effects of the Sun," Professor Stone tells me, "that's how the Sun was eight minutes ago. But when you get a message from Voyager, that's how it was 16 hours ago."

He seems to relish the scale of the numbers - and is obviously used to having a reporter stand open-mouthed beside him.

The Voyagers, he says, are travelling at 17 kilometres per second (38,000 mph). And their computing power? A decent smart phone has ten million times more memory than all three on-board computers combined.

Yet what they have shown us still inspires. Among many revelations, Jupiter's moon Io was seen to be the most volcano-wracked body in the Solar System and Neptune's deep-frozen moon Triton to be blasted by geysers.

And then the little craft ventured beyond the orbits of the planets - further than any other manmade machines - and entered a region labelled with a bizarre vocabulary unfamiliar to most of us.

Golden records containing sounds from Earth were carried aboard both spacecraft

They travelled through the exotically-named "termination shock" - where the Sun's flow, or wind, of particles suddenly decelerates.

Now they're in the heliosheath - the outer zone of the Sun's influence. At some unknown point they'll cross the heliopause, defined as the final limit of the Solar System.

Then they'll enter interstellar space - the void between stars - where our Sun will become just another speck, one among billions.

According to Professor Stone, with four instruments still working on Voyager 1 and five on Voyager 2, new findings are made almost every day.

Sensors measure the speed and density of the solar wind, the magnetic field, energetic particles and radio waves - all providing clues about the pioneering moment when humankind will first venture beyond the Solar System.

Borrowed time

I ask why he thinks the Voyager expedition attracts such support and so much attention. It's a mission everyone loves to hear about.

"It's the urge," he says, "to explore our solar neighbourhood and now we're about to explore outside our solar bubble. It's remarkable how it resonates with the public."

So, what next?

The plutonium power source will stop generating electricity in about 10-15 years and there's no way to extend it so the spacecraft's electronic systems will die. No more messages will be sent after 2025.

"Then they'll become silent ambassadors orbiting around the centre of the Milky Way."

And where are they heading once they leave the Solar System?

Voyager 1 is on course to approach a star called AC +793888 - but it will only get within two light-years of it.

Voyager 2 is hurtling towards another star named Ross 248 - but, again, even at its closest, it will still be a whole light-year away.

And when are these encounters due? Professor Stone can't help laughing with delight. He knows his answer will amaze me.

"In about 40,000 years' time."

- Published9 June 2011

- Published14 December 2010