Animal experiments increase again

- Published

GM animals and "harmful mutant" animals largely account for the rise

The number of animal experiments carried out in the UK rose by 3% last year, according to government figures.

The rise was largely due to an increase in the use of genetically modified (GM) and mutant animals, a trend that shows no signs of abating.

The news comes as campaigners warn a new EU directive threatens standards of welfare for UK lab animals.

They argue that a number of the directive's regulations fall short of those already in place in the UK.

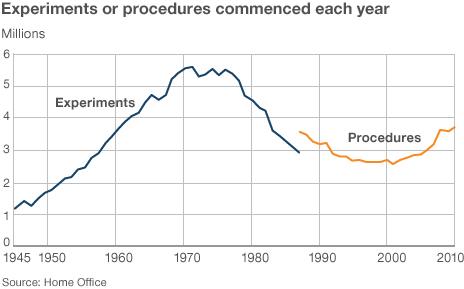

Just over 3.7 million scientific experiments on animals were started in Great Britain in 2010, an increase of 105,000 on the previous year.

The statistics show that breeding to produce genetically modified (GM) animals and harmful mutants (an animal with potentially harmful genetic defects) rose by 87,000 to 1.6 million procedures.

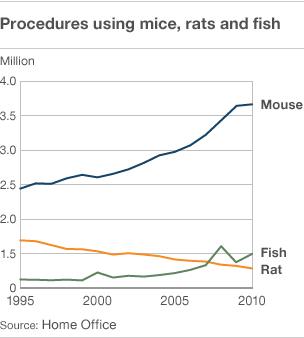

This rise, mainly due to the increased breeding of mice and fish, represents an increase of 6%.

Two-thirds of the genetically modified animals used are bred to maintain stocks and set up genetic crosses, and so are not directly used in experiments.

The growing numbers of fish used in experiments are because of an increasing reliance of zebrafish, which are transparent and therefore very useful for studying how bones and other tissues develop.

When GM animals are excluded from the statistics, the total number of procedures rose by 18,000, from 2.09 million to 2.10 million.

Home Office minister Lynn Featherstone commented: "The figures released today once again show the important work being done in this country to regulate animal procedures and ensure the highest standards of animal protection are upheld.

"The UK has one of the most rigorous systems in the world to ensure that animal research and testing is strictly regulated."

Neurobiologist Roger Morris at King's College London stressed that whenever possible scientists studied diseases in a dish, in an effort to avoid the use animals. But when studying the effects of a disease on the entire body, he said, there was currently no alternative to using an animal model.

The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) has warned that a new EU directive could threaten this system.

"The RSPCA is deeply concerned and very disappointed that the numbers of animals used in research and testing has gone up yet again," said Penny Hawkins, senior scientific officer at the organisation.

It says that if the UK chooses to amend its own regulations in line with the minimum requirements of the directive, some animals could be allowed to suffer "severe" pain or suffering.

Dr Maggy Jennings, head of the RSPCA's research animals department, said: "Successive governments have made proud claims that the UK has 'the highest standards in the world' for animal research and testing.

"Now they seem prepared to weaken this legislation and take a step backwards on lab animal welfare."

However, Martin Walsh, head of the Home Office's Animals Scientific Procedures Division, said: "The directive does allow us to keep the higher UK standards that we currently have. It is not going to reduce the protection of animals in the UK."

Kailah Eglington, chief executive of the Dr Hadwen Trust for Humane Research, said: "It is very disappointing that there has been a 3% rise in levels of animal procedures since 2009.

Ms Eglington added: "Therefore, the recent announcement of a public consultation on the new EU Directive provides a vital opportunity for the Government to hold true to its Coalition pledge to reduce the use of animals in experiments and we urge the Government to focus on the development of techniques to replace animal use for scientific purposes."

Troy Seidle, director of research and toxicology for Humane Society International UK, said: "Britain is Europe's second largest user of animals for research, with the number of animal experiments having grown steadily over the past decade, particularly in the university sector."

In its statement the Humane Society International urged the government to reduce animal suffering and improve the quality of medical research by replacing "failing animal models with more advanced alternative techniques".

The way experiments/procedures were counted /defined changed under the terms of the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986