On the shoulders of space giants

- Published

- comments

"We wouldn't be able to do today what we do unless someone had flown first - and that was Yuri Gagarin"

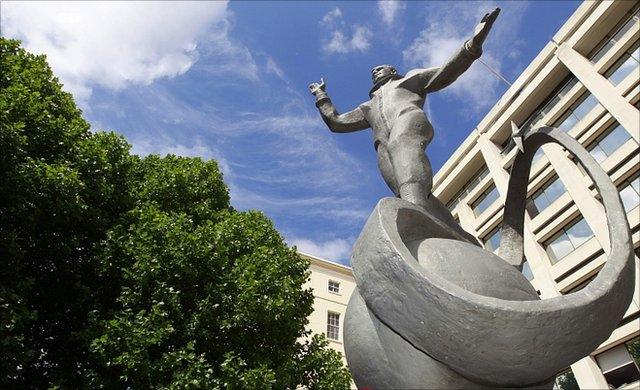

London paid tribute to Yuri Gagarin on Thursday, unveiling a statue of the cosmonaut just a few metres back from The Mall.

The figure stands, arms outstretched, looking across the road to another great explorer, Captain James Cook.

Gagarin's achievement in circling the Earth on 12 April 1961, external still seems remarkable - a step into the complete unknown.

His link with the UK goes back to the world tour he undertook shortly after returning to Earth. He was invited to Britain by the National Union of Foundrymen.

It was said the UK government at the time didn't really know how to react to his visit and was initially reluctant to get too involved. Only when it saw how warmly and enthusiastically the British people welcomed the Soviet spaceman did the London government decide to roll out the red carpet.

He met the Queen - as you do - and the then Prime Minister Harold MacMillan. The latter encounter took place at Admiralty Arch - one good reason to site the statue close by.

Krikalev has clocked more than 800 days in orbit

The other good reason is that it is right outside the British Council's headquarters, external. The Council, in the form of its director of visual arts, Andrea Rose, had been trying to get a Henry Moore sculpture to Moscow to be part of an exhibition in the Kremlin Gardens. In return, Rose wanted a Gagarin figure to come back to London.

Well, the Moore sculpture was never permitted to leave its home in Parliament Square, but she did get her alloy cosmonaut.

The figure is a copy of one found in the town of Lubertsy, just outside Moscow, where Gagarin trained as a foundry worker when he was little more than 15 years of age.

Lubertsy, understandably, was reluctant to let the original go abroad, even on loan, so the Russian space agency (Roscosmos) paid for a replica to be fashioned and shipped to Britain. And in Thursday's crowd, I found a man who has special reason to celebrate the pioneer Gagarin.

This was Sergei Krikalev, external, the most experienced spaceman in history.

Krikalev has clocked more than 800 days in orbit, external on six missions - to Mir and the International Space Station (ISS).

Krikalev, you may recall, was the man they dubbed "the last citizen of the USSR" because in the 300-plus days he spent on Mir in 91/92, the Soviet Union collapsed.

Today, Krikalev is the head of the Gagarin Training Centre, Star City. All the cosmonauts/astronauts that come through the centre will have learnt something from him. So what, I wondered, did he think of Yuri?

"We wouldn't be able to do today what we do unless someone had flown first - and that was Yuri Gagarin," he told me.

His six flights included two shuttle missions

"That's why Neil Armstrong when he stepped on the Moon said, 'Gagarin called all of us into space'. We just followed his steps.

"From his one orbit in little more than an hour, we now do multi-orbit, multi-month missions. And now it's all international co-operation - multi-tonne space-station modules built in different countries."

Krikalev's record is 803 days and nine hours and 39 minutes in space. If one does, let's say, nearly 16 orbits a day on the ISS, it means Krikalev must have circled the Earth well over 12,500 times.

There has been a lot of talk in recent days about the last space shuttle mission and the end of an era.

Krikalev flew on the shuttle twice - on his first flight with Charlie Bolden, then the ship's commander and now Nasa Administrator; and on the second to make the first delivery of a US module to the fledgling ISS.

"I have a sad feeling to see the end of shuttle, the same as I felt to see the end of Mir," he said. "But shuttle was a great programme and the space station would not have been possible without it.

"We will push out; we will eventually go beyond the space station. But even staying in the Earth's orbit, we are not repeating what we've done in the past. It's like the Romans who moved up and down a road. We move up and down that same track but today we travel in a high-speed train, so you cannot say nothing's changed. I am excited about the future."