Environment: The case against protection

- Published

- comments

This will be the last post for a few weeks as holidays beckon.

So why not leave you with perhaps the biggest question in the environmental book - where is the natural world heading, if nothing much changes?

Simply protecting land and sea won't be enough to stem the loss of nature, according to a study just out, external in the Marine Ecology Progress series.

Read it one way, and it's one of the most depressing things you'll have seen, if you're concerned about the biosphere's future.

Currently, about 13% of the world's land surface is under some form of protection, about half of which is under what a recent study, external evaluated as "strict" protection.

At sea, it's a different story, with protection hovering around the 1% level - depending on how you define it.

So if land protection is in one sense a success story, being a rare example of an internationally agreed target that has been met and indeed exceeded, external, what impact is it having on biodiversity loss?

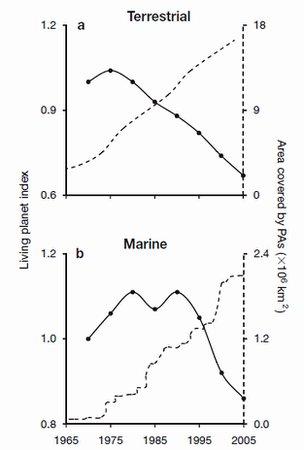

The various graphs in the paper, some of which I've copied in here, tell the story better than any of its words.

Even as protected areas expand, indices of biodiversity such as the Living Planet index decline

In region after region, the line indicating protection tracks upwards, even as measures of biodiversity point the other way.

So is there any point in protecting habitat?

When I called up one of the authors, Camilo Mora, external from the University of Hawaii, he was at pains to point out that an end to protection was not on his agenda.

"Protection is necessary - but far from sufficient," seems to be the overall message.

"We're definitely not saying we shouldn't protect areas - the problem is that we're investing all our human capital into those areas," he told me.

"We're putting all our eggs in one basket, which is dangerous; but even more dangerous is that there's a hole in the bottom of the basket."

The force they flag up as driving the world's biological diversity to the edge and perhaps beyond is, simply, that we are consuming too much.

That won't be a revolutionary message to some.

But the authors believe it's something that many more policymakers and ordinary citizens have to put at the centre of their thinking if the sixth great extinction is not to exceed the five previous ones in scale and rate.

Another of the authors, Peter Sale, external from the Canadian Institute for Water, Health and the Environment, put it like this:

"We are just taking too much - managing forests in such as way as they degrade, same with coastal waters, and we have to stop doing this as a species.

"I don't have a solution - I have struggled for some time trying to think what is the way to get people to realise how important this is - but if we don't find it soon, the future is a very grim one.

"We're talking about losing 50% of species in the next half century - that's faster than any previous mass extinction event - and anybody who thinks we can go through a mass extinction and be perfectly fine is just deluding themselves."

Cutting consumption does not appear on the agenda of most governments

There's some implied criticism for mainstream conservation groups here.

The authors suggest these groups concentrate too much on protected areas, and ignore the issue of over-consumption.

In my own experience, that's not entirely correct.

It's more that conservation, being an element of the political process, is in large part the art of the possible, external.

And while getting governments to set areas aside for tigers or sharks is doable, there are few ready to lend an ear to the politically suicidal idea of reducing their citizens' consumption.

It's also controversial inside the wide umbrella of civil society.

Organisations such as Oxfam, for example, which campaign on climate change, are there in large part to advance the cause of the global poor - and that doesn't mean reducing their consumption of food or fuel.

Changing the nature of what we consume is seen in some quarters as more feasible - eating locally-produced food, powering society with renewables rather than fossil fuels - but so far, it's making merely a dent in the overall upwards trend of us guzzling more and more stuff.

And this is only augmented by the growth of the world's human population, set to top seven billion, external before the end of the year.

As with domestic politics, attempts to get sustainable consumption onto the international agenda have thus far been an almost total failure.

The next big set-piece chance to discuss it is the Rio+20 summit, external next May.

The issue has been mentioned and discussed by governments in the preparatory process, and there are nods to it in some of the outline documents.

For example: "...certain types of consumption and investment must be restricted to avoid excessive resource depletion and waste, whereas environmentally-friendly investment and consumption should expand..."

But you would have to ask how urgent, how quantified, how serious this really sounds...

...especially when you set it alongside one of the papers cited in the new Sale and Mora paper - that by 2050, the human race will be consuming so much of nature's resources than in order for this to come at a sustainable rate, we would need to be drawing on the resources of 27 Earths.